Placenta

The placenta is one of the most powerful temporary organs of the human body. It releases its own hormones, provides nutrients to the fetus, filters out waste, and establishes an intricate network of blood vessels that connects the health of the mother to the health of the fetus.

The placenta is also connected to critical aspects of obstetric health which include preeclampsia, growth restriction, high blood pressure, miscarriage, infection, and teratogens – yet the organ remains very understudied (due to research hurdles). However, further research can help answer the placenta's role in the above complications and help determine the causes of specific disorders.

Additionally, there are numerous possible disorders regarding placenta development, from size and location to level of adherence. The placenta may also play a role in postterm pregnancy complications but evidence remains conflicted whether the placenta (or amniotic fluid) is the primary cause of these complications.

Regardless, the placenta is unequivocally a major factor in all facets of pregnancy and a healthy placenta is critical for a healthy pregnancy. Therefore, learning about this organ can help women better understand not only their baby's health during pregnancy but their own health as well.

Background

Graphic warning: A photo of a placenta is in the "Removal" section.

The placenta, an understudied major endocrine organ, has been documented to be the most important temporary organ in the human body. The placenta produces hormones that have a significant impact on both the pregnant woman and fetus; many common complications in pregnancy can be traced to hormonal effects of the placenta.

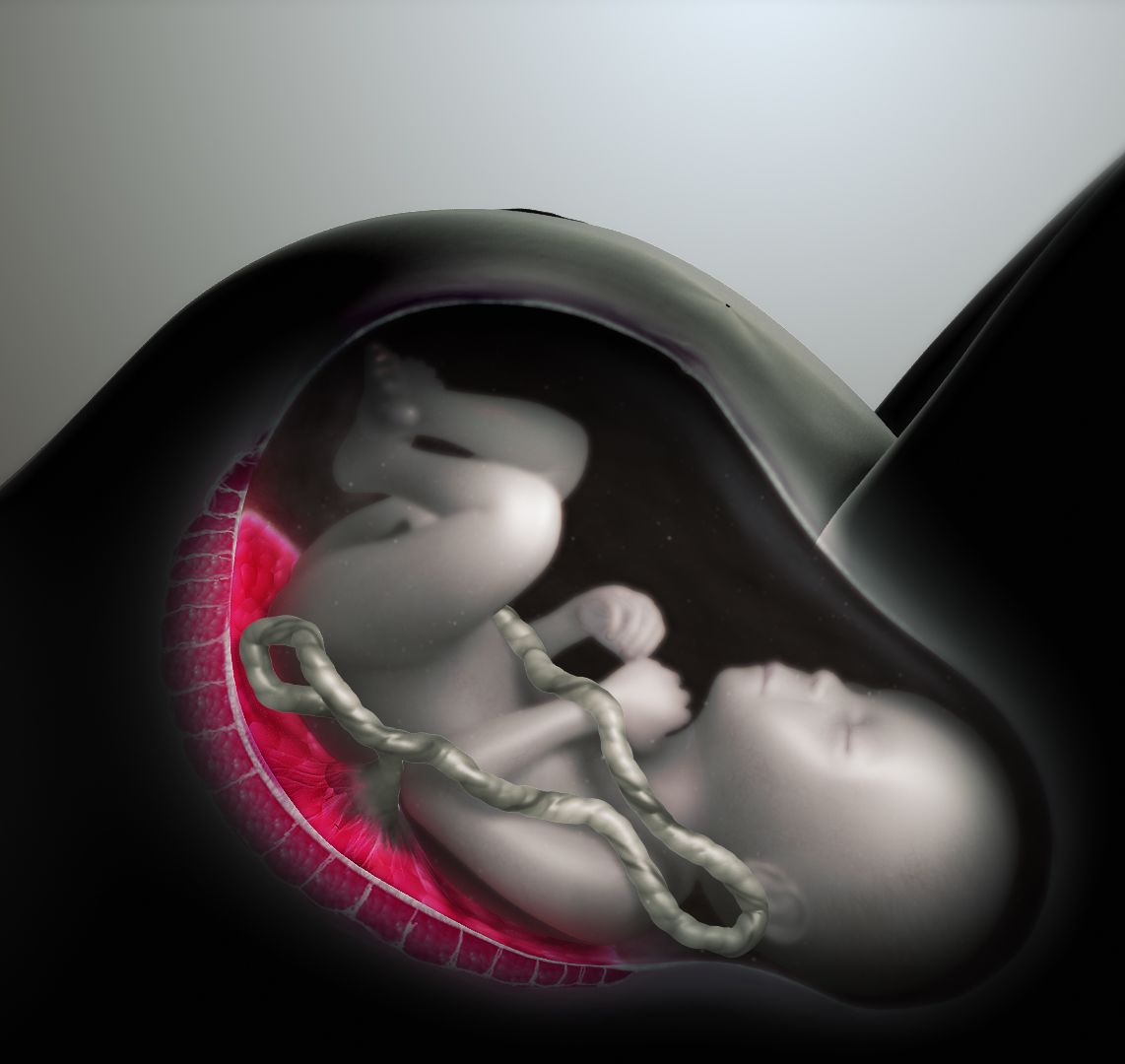

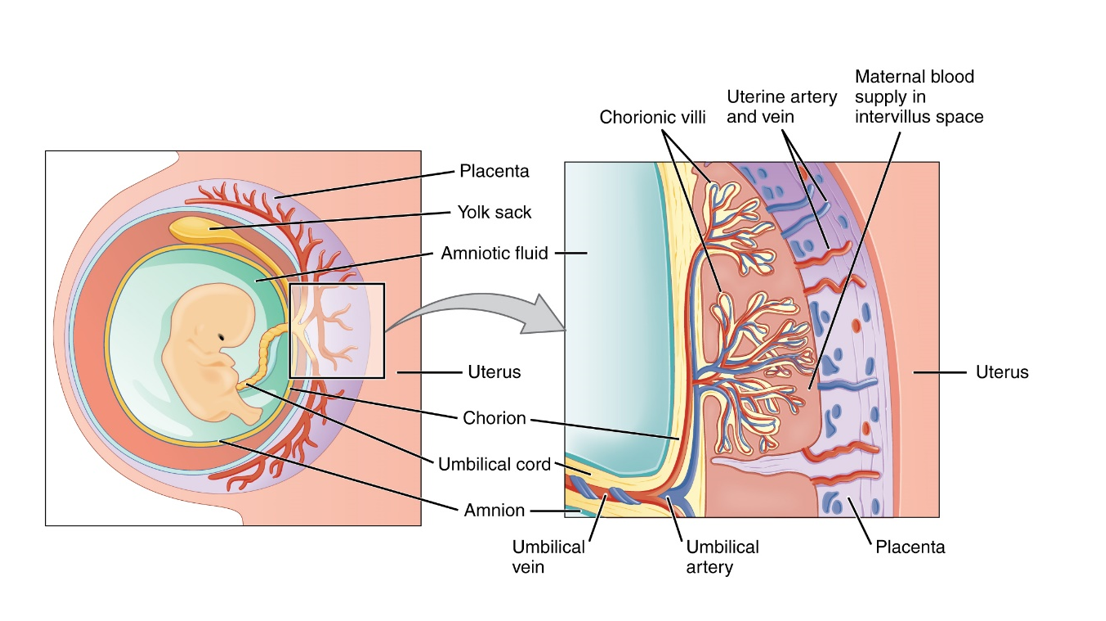

The placenta attaches to the lining of the uterus and is connected to the fetus by the umbilical cord. The placenta provides oxygen and nutrients to the fetus, removes carbon dioxide and other waste products, protects the fetus from most infections and disease, and produces hormones necessary to sustain a healthy pregnancy. The placenta also acts partly as the fetus’ lungs, kidneys, and liver.

To achieve proper maternal-fetal oxygen, waste, and nutrient exchange, the developing placenta must:

Implant into the uterine wall

Remodel maternal spiral arteries of the uterus so that blood flow delivery can increase in capacity (did you know: a failure of this remodeling can lead to preeclampsia and/or fetal growth restriction)

Produce "villous trees" (specialized blood vessels) — to increase the surface area for this exchange to occur

Increase in size over the course of pregnancy to accommodate the increasing needs of the fetus as it develops

First Trimester

When the early blastocyst implants, it begins a reaction in the uterine lining that thickens and begins to form the placenta, which is mostly filled with clear fluid for the majority of the first trimester. A complete network of blood vessels is established by the end of the 6th week.

The placenta can be attached to the top, side, front or back of the uterus. There is conflicting information regarding the difference between anterior and posterior placental locations and possible complications during pregnancy and/or labor. However, the placenta can migrate to different positions as the uterus enlarges.

In early pregnancy, progesterone is produced by the corpus luteum until this job is eventually taken over by the placenta, with the transfer process beginning and ending anywhere between 8 to 12 weeks of pregnancy.

Although debated, it is currently assessed the blood vessel connection between mother and placenta is not fully established until 12 to 14 weeks of pregnancy, when a three-fold rise in oxygen concentration can be observed in the placenta.

There is no direct mixing of blood between the mother and fetus. The mother’s blood enters the intervillous space of the placenta through about 100 spiral arteries, covers the villi, and leaves via the veins. The placenta will eventually contain approximately 150 ml of maternal blood that is replaced about three to four times per minute.

Second Trimester

By 17 weeks of pregnancy, placental and fetal weights are approximately equal.

The placenta continues to grow rapidly in size and thickness until 20 weeks of pregnancy.

Although placental size can vary, the fully developed placenta covers 15% to 30% of the uterine lining and weighs about one-sixth as much as the fetus. A typical placenta weighs about 1 to 1.5 pounds (470 grams), 15 to 22 centimeters (cm) in diameter, and about 2.5 cm thick.

A smaller than normal placenta is associated with intrauterine growth restriction and preeclampsia (likely due to blood vessel problems), while a larger than normal placenta is associated with maternal diabetes, intrauterine infection, and fetal hydrops (excessive accumulation of fluid).

Third Trimester and Postterm

It is widely believed the placenta ages and declines around 36 weeks of pregnancy, especially at term, and is usually cited as a cause to induce labor.

Other research indicates the placenta continues growing completely through delivery. It is possible that growth slows, but it does not stop, and continues to produce hormones even after 42 weeks.

However, there is strong evidence that pregnancies beyond 42 weeks are at increased risk for severe complications, but the placenta may not be the cause.

Amniotic fluid reduces in postterm pregnancies, which may play the primary role in complications. However, it has also been stated that the aging placenta is the cause of the decrease in fluid, but other research disagrees and indicates the placenta plays no part. Therefore additional research is necessary regarding placental health near and after term.

Environment

Researchers did not know that certain environmental agents (medications, chemicals, viruses, bacteria) could pass through the placental membrane until the 1940s and 1950s (read Teratogens).

Instead of a complete barrier, the placental membrane acts like a filter during pregnancy and there are only a few substances that do NOT pass through (in measurable amounts). Interestingly, this "filter" changes throughout pregnancy, and substances that could pass through early in pregnancy may not be able to pass through later in pregnancy (as well as the reverse).

This science, determining which agents pass through the placenta, is the key factor in identifying substances a fetus could potentially be exposed to that may either have a harmful or beneficial effect.

Some harmful substances known to pass from the mother to the fetus via the placenta include alcohol, certain medications, and chemicals associated with smoking.

There are also beneficial substances that pass through, to include antibodies (read Vaccines), glucose, oxygen, hormones, vitamins, and minerals. Note: Researchers are trying to determine medications that can be taken by the mother and pass through the placenta to potentially treat medical conditions in the fetus – prior to delivery.

So why do some substances pass through to the fetus but others do not? (most viruses do NOT pass through, or do so rarely):

The physical properties of the placenta and agent explain this. Whether a substance can pass through the placenta depends on (just a few examples):

Placental surface area and thickness (the placenta grows throughout pregnancy)

Villus diameter (vascular projections of placental tissue that help increase surface area for maternal/fetal nutrient exchange)

Number of microvilli (the placental barrier develops thousands of microvilli (small than villi, above) exposed to maternal blood which regulate agent transfer between mother and fetus)

pH of maternal and fetal blood

Blood flow of uterus/placenta (mL/min)

Molecular size of the agent (may be most impactful); agents with a larger molecular size cannot pass through the placenta; for example, antibodies IgG and IgE can pass through, but not IgM, which are the first antibodies created from an infection. (See COVID-19 for more information on antibody transfer to fetus from vaccines.)

The second part of this equation: Even if a substance passes through the placenta, in what quantity does it pass through, is the fetus exposed, and what is the effect on the fetus? These questions remain unanswered for a vast majority of agents, most of which are medications (read Teratogens for more information).

There are also additional environmental factors, not impacted by placental transfer, that could impact the mother's health and/or the health of the placenta, such as:

Maternal age

High blood pressure

Carrying multiples

Blood-clotting disorders

Previous uterine surgery

Previous placental problems

Substance abuse

Physical trauma

Placental Disorders (in Brief)

When the placenta fails to operate normally, this is associated with a number of different maternal (preeclampsia) and neonatal complications (growth restriction).

More specifically, there are several conditions associated with placental and blood vessel location and attachment, such as placenta abruption, previa, and accreta spectrum (which includes increta and percreta).

Placenta previa: occurs when the placenta develops over the cervix

Placenta accreta: abnormal adherence of part or all the placenta to the uterine wall

Placenta increta: abnormal adherence of the placenta through the uterine wall and into the endometrium

Placenta percreta: abnormal adherence of the placenta through the myometrium and into the uterine serosa (outermost layer of the uterus); placentas can also grow out of the uterus and into other nearby organs

Circumvallate placenta: occurs when the membranes of the placenta “double back” to make a thick ring around the edge of the placenta; upon removal after delivery, the placenta looks like it has a thick extra layer

Vasa previa: occurs when blood vessels from either the placenta or umbilical cord cross over the cervix

Succenturiate placenta: an extra lobe of the placenta grows some distance away from the main body of the placenta; blood vessels may run unprotected between both sections – if these blood vessels cross through or near the cervix, this also leads to vasa previa

Velamentous placenta: occurs when placental blood vessels grow through the fetal membranes (amnion and chorion) and away from the placenta

Abruption

Placental abruption occurs when the placenta either partially or completely peels away from the inner wall of the uterus before delivery. Abruption is an emergency and usually requires immediate delivery as it can cause excessive bleeding and a dramatic decrease in oxygen to the fetus.

Symptoms of placental abruption vary, but often include vaginal bleeding and abdominal or pelvic pain.

Women should seek emergency care if they experience any bleeding in the second or third trimesters, as bleeding could get worse quickly.

Previa

Placenta previa occurs when the placenta partially or totally covers the cervix and can cause severe bleeding during pregnancy or delivery. The exact cause of placenta previa is unknown, but the condition occurs in about 1 in 200 pregnancies.

A placenta is termed “low lying” when the placental edge does not cover the cervix, but is within 2 cm of it.

If the placenta is anchored to the bottom of the uterus, the thinning and spreading as the uterus enlarges separates the placenta and causes bleeding. Ultrasound is used to confirm diagnosis.

Women with previa may bleed throughout their pregnancy and during delivery; delivery is not immediately necessary, especially early in pregnancy as the previa may also resolve as the uterus grows.

However, women should always seek emergency care if they experience bleeding during the second and third trimesters, even light bleeding, as the bleeding could become worse very quickly.

Not all women with placenta previa will have vaginal bleeding, and in those cases, diagnosis is usually made during a routine ultrasound exam. Any exam requiring an internal pelvic exam will be avoided to prevent disturbing the cervix in any way.

Risk factors include prior previa, cesarean section, or prior uterine surgery, as well as smoking, using cocaine, maternal age, carrying multiples, and use of in vitro fertilization.

Method and timing of delivery depends on the amount of bleeding, whether the bleeding stops, how far along the pregnancy is, the position of the placenta, and the overall health of the baby and mother.

If severe bleeding occurs at any time, immediate delivery via cesarean section may be required. If bleeding is not severe, and occurs only once, careful monitoring is advised, with hospital admission likely occurring after a second episode.

Women may also need to avoid activities that could cause contractions or increase the risk of bleeding, such as sex, running, squatting, jumping, and other forms of exercise.

Accreta

Placenta accreta spectrum refers to the range of invasion or adherence of the placenta and includes placenta increta, placenta percreta, and placenta accreta. Partial or complete adherence of the placenta to any part of the uterus after delivery can cause severe bleeding. Note: Despite the adherence, the placenta functions normally.

Accreta: placenta is firmly and strongly attached to the uterine lining

Percreta: placenta grows through the uterine wall

Increta: placenta grows into the muscles of the uterus

Although still rare, incidence of placenta accreta (full spectrum) has increased in the past from 1 in 30,000 in the 1950s, to 3 in 1,000 in the early 2000s, to about 1 in 700 today, most likely due to the increasing cesarean section rate.

Accreta occurs most often in women who had a prior cesarean section or prior placenta previa.

In one study, the rate of placenta accreta spectrum increased from 0.3% in women with one previous cesarean delivery to 6.74% for women with five or more. This risk is dramatically higher for women who have had both prior cesareans and placenta previa.

The leading hypothesis for what causes accreta, especially in the case of prior cesarean section, is a defect in the uterine lining that leads to a failure of normal decidualization in the area of a uterine scar, which allows for deep and abnormal placental invasion. This may be the same mechanism behind prior uterine surgeries, which is also a risk factor.

Additional risk factors include advancing age, more than one fetus, high second trimester levels of human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG), fibroids, and Asherman syndrome.

However, it is likely there are additional causes, as women with no prior history of cesarean sections, placental disorders, or uterine surgeries also experience accreta.

Diagnosis of accreta is usually made in the second and third trimester during an ultrasound examination; the first trimester is likely too early for diagnosis. About 80% of accretas are estimated to be diagnosed before delivery because the presence of placental previa was noted via ultrasound first, which later led to an accreta diagnosis.

Other placenta accreta spectrum diagnoses are unexpectedly recognized at the time of delivery – both vaginal and cesarean – when the placenta does not dislodge as expected.

Manual removal of the placenta can result in massive postpartum hemorrhage; therefore, treatment for accreta spectrum is almost always hysterectomy (removal of the uterus).

If the diagnosis of accreta is made prior to delivery, a cesarean section is scheduled, followed by a hysterectomy, usually with the placenta still in place to avoid catastrophic bleeding. The optimal timing for scheduled delivery is not clear and depends on the overall health of the mother and fetus but is normally between 34 and 37 weeks.

Hysterectomy is usually always necessary, but in rare cases, can depend on the level of invasion. Other options may be available on an individualized basis and the assessment/recommendation of the woman's HCP.

It is possible for the uterus to be left in place, and a high dose of methotrexate can be given to dissolve the placenta. Uterine artery embolization, arterial ligation, and balloon tamponade are also sometimes used, but are not very effective and carry great risk of hemorrhage.

Removal

In vaginal delivery, removal of the placenta is also known as the third stage of labor (read more detailed information). In a cesarean section, the HCP removes the placenta during the procedure.

The part of the placenta attached to the mother is dark red in color and bleeds due to torn blood vessels from detachment. The fetal side can be bluish in color, and 8 to 10 blood vessels are usually apparent.

This image contains triggers for: Blood, Internal Anatomy, Real Delivery

You control trigger warnings in your account settings.

Action

Women need to call their HCP immediately anytime they experience vaginal bleeding during pregnancy, or visit an emergency room. Although placental conditions most likely occur after the first trimester, first trimester bleeding, with abdominal pain, could indicate ectopic pregnancy, which also considered in an emergency and needs to be ruled out (read Vaginal Bleeding).

Resources

Placenta (Society for Endocrinology)

Human Placenta Project - Illustrations (Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development)

Placenta Development (UNSW Australia/Embryology; Dr. Mark Hill)