COVID-19 Infection

*NEW (18 October 2022): "Long-COVID" section added.

*NEW (15 October 2022): "Specific Variants and Pregnancy" section added.

According to currently available case series and cohorts as of October 2022, data indicate pregnant women are not more susceptible to contracting COVID-19 than non-pregnant women, and fetal and symptomatic neonatal infection appear to be rare events.

However, pregnant women who contract COVID-19 appear to be at higher risk of certain complications from the disease than non-pregnant women of reproductive age. These complications include Intensive Care Unit admission, mechanical ventilation, and the need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), as well as the risk of death (although overall risk remains low).

Research indicates pregnant women can experience a complete lack of symptoms (asymptomatic) to a wide range of acute and long-lasting symptoms, similar to the general population. These include fever, shortness of breath, cough, nausea, congestion, runny nose, vomiting, diarrhea, chills, loss of smell, sore throat, headaches, body aches, and excessive phlegm.

Therefore, pregnancy remains a risk factor for possible severe infection. Any pregnant woman experiencing one or more of the above symptoms should call her health care provider (HCP) for an evaluation.

Women also need to report to their HCP any exposure they have had to an individual with confirmed or suspected COVID-19. As pregnant women can experience asymptomatic infection, some HCPs may recommend these women be tested, especially women with certain underlying conditions (obesity, diabetes, hypertension, asthma).

For detailed information on the safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination and its effects on fertility, pregnancy, and breastfeeding, click here.

Women should ask their HCP any questions or concerns they have regarding COVID-19 or its vaccines and visit the CDC website for more information.

*If you are experiencing trouble breathing or extreme shortness of breath, seek emergency medical care immediately or dial 911*

Recent Publications (all Sections)

October 17, 2022: While this study did not primarily assess for Long-COVID, researchers recruited 84 pregnant women with mild COVID-19 and 88 pregnant women without COVID-19. All participants were unvaccinated. Of the 83 participants who attended the follow-up for post-COVID-19 symptoms, 63 of them (75.9%) presented with Long-COVID, with the most common symptoms being shortness of breath, fatigue, headache, and loss of taste and/or smell. The median duration of long COVID symptoms was 60 days.

October 7, 2022: In Scotland, between May 17, 2021, and January 31, 2022, there were 9923 COVID-19 infections in 9823 pregnancies, in 9817 women. In this cohort, pregnant women infected with COVID-19 were substantially less likely to have a preterm birth or maternal critical care admission during the omicron-dominant period than during the delta-dominant period.

October 7, 2022: Study found a high rate of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (high blood pressure) overall in all those affected by COVID-19, regardless of severity. Pregnant women diagnosed with COVID-19 should ensure their HCP is aware to allow for closer monitoring of blood pressure, even after recovery.

October 1, 2022: In this research letter, the authors describe the use of anti-spike monoclonal antibodies to treat mild to moderate COVID-19 in 47 pregnant patients. The authors found no conclusive evidence of maternal or fetal complications due to the treatment. Only two patients had progression of the disease and only one required hospitalization.

September 16, 2022: In this study, researchers detected COVID-19 in syncytiotrophoblast tissue (part of the placenta that is between maternal and fetal blood) and fetal tissue between weeks 8 and 12 of pregnancy. The results suggest that COVID-19 vertical transmission is indeed possible during the first trimester, even in pregnant women with no symptoms (but is still rare).

September 12, 2022: Study showed that antibodies in breast milk from participants with recent COVID-19 infection and those who recovered can neutralize the spike complex. This finding further emphasizes the passive protection against COVID-19 conferred to infants through breastmilk.

Overall Key Findings

Overall, pregnant women do not appear to be at an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 over non-pregnant women (i.e. same infection rate).

However, pregnant women appear to have an increased risk of intensive care unit (ICU) admission, mechanical ventilation, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), as well as death (but overall risk is low).

Rates of pneumonia and preterm delivery may also be increased compared to pregnant women without infection, but these results are inconsistent.

There is a significant racial disparity; pregnant Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black women experience even higher risks of complications from COVID-19 infection.

Regarding fetal and neonatal health, current results are reassuring and indicate newborns of mothers who contract COVID-19 appear to be born healthy.

Current evidence also indicates the virus does not readily cross the placenta or infect the fetus. Although there are case reports of this occurring, the event appears to be rare and likely depends on severity of infection.

However, in some instances, COVID-19 infection can cause inflammation of the placenta, known as COVID (or SARS-CoV-2) placentitis. Placental inflammation can negatively impact fetal growth and development.

Preliminary research indicates COVID-19 infection in early pregnancy does not appear to increase the risk of miscarriage, but more research is necessary.

Infant infection from exposure to an infected parent or caregiver likely accounts for most infections reported in newborns; majority of these infections appear to be asymptomatic or mild.

There is currently no evidence that COVID-19 infection can be transferred to the baby through breast milk; breast milk of previously infected mothers appears to contain COVID-19 antibodies (no reason to separate mother and baby after delivery).

There is currently no long-term data on how COVID-19 infection during pregnancy could affect women or their babies.

Background

In December 2019, health officials in China indicated they had a serious outbreak of a respiratory illness caused by a new type of coronavirus, COVID-19, or “coronavirus disease 2019”.

In February 2020, the virus was given the specific name “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2” or SARS-CoV-2. In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially declared the outbreak a worldwide pandemic.

This page will refer to SARS-CoV-2 as COVID-19.

Various coronavirus infections during pregnancy – such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle-East respiratory syndrome (MERS) – have been associated with a higher incidence of severe illness in the mother and adverse outcomes for the fetus.

Fortunately, current evidence indicates that COVID-19 is significantly less lethal than SARS and MERS. However, pregnant women do appear to have a higher risk of certain complications over non-pregnant individuals with COVID-19.

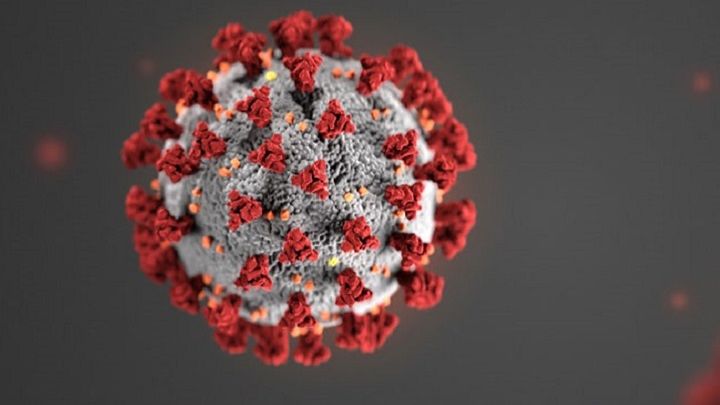

The term coronavirus derives from the Latin word corona, which means crown or halo. Under electron microscopy, the virus particles display a crown-like pattern on its outside, similar to spikes, which has resulted in the very common computer-generated image of the virus below. In general, coronaviruses cause illnesses ranging from asymptomatic infection to fatal infection.

There are seven coronaviruses currently infecting humans. COVID-19 is the third coronavirus to cause a major epidemic, after SARS and MERS. However, COVID-19 has infected a far greater number of people than SARS and MERS combined.

Information on the effects of SARS and MERS during pregnancy was being used early in the pandemic to help manage pregnant women with COVID-19. However, more current data has shown several differences between SARS, MERS, and COVID-19, with data indicated COVID-19 is far less lethal in pregnant women compared to SARS and MERS.

Symptoms of SARS consisted of fever, chills, headache, general discomfort, muscle pain, and diarrhea, with an incubation period of around 4.6 days, but a range of 2 to 14 days. Almost all patients contracted pneumonia. Case fatality rate was estimated at 9% to 10%.

SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19)

Sequencing data show that COVID-19 has a 79% genetic similarity to SARS and about 50% to MERS. However, updated in October 2022, COVID‐19 has an overall significantly lower fatality rate, estimated around 1.1% in the United States (0.9% in the UK, 1.1% in Canada, and 0.2% in Australia). Pregnant women appear to have the same fatality rate as non-pregnant women.

Human-to-human transmission occurs through close contact via respiratory droplets; incubation time averages 4 to 5 days but can range from 1 to 14 days. It is estimated almost all infected individuals develop symptoms by 11.5 days.

Infected droplets can also spread to distances of up to 6 feet and deposit on surfaces (fomites). These fomites can then infect healthy individuals who touch the unsanitized surface and then touch their mouth, nose, or eyes.

COVID-19 infection can be described in 3 stages:

Stage 1: Incubation period; may include asymptomatic infection

Stage 2: The virus is detectable and presents with minor or mild symptoms such as a fever

Stage 3: Severe symptoms arise which may require hospitalization and could result in respiratory distress or death

Individuals can experience a complete lack of symptoms to a wide range of acute and long-lasting symptoms. These include fever, shortness of breath, cough, nausea, congestion, runny nose, vomiting, diarrhea, chills, loss of smell, sore throat, headaches, body aches, excessive phlegm, coughing up blood, pneumonia, and blood clotting issues.

COVID-19 Infection in Early Pregnancy or when TTC

As of December 2021, it does not appear that COVID-19 infection early in pregnancy increases the risk of miscarriage, but laboratory results and placental examination after pregnancy loss in COVID-19 positive women have indicated it is possible (although likely rare):

At least three studies assessing whether COVID-19 had any impact on early pregnancy loss determined that infection appears to have a favorable maternal course at the beginning of pregnancy and does not appear to increase the risk of miscarriage.

A nationwide study published in June 2021 indicated the risk of pregnancy loss at less than 20 weeks gestation due to COVID-19 was similar to the rate of early pregnancy loss in pregnant women without COVID-19 infection.

However, at least three separate studies (from August/September 2020 and July 2021) identified COVID-19 receptors in the early oocyte and blastocyst; therefore, it is possible that infection in early pregnancy could have adverse effects on the embryo. Significantly more research is necessary in larger populations of women.

A case study published in March 2021 found COVID-19 nucleocapsid protein, viral RNA, and particles in the placenta and fetal tissues of an early pregnancy miscarriage from a pregnant woman who had tested positive for the infection. The study also determined that fetal organs, such as lung and kidney may be targets for coronavirus. For more information, see "COVID placentitis" in the section below.

Regarding fertility and trying to conceive (TTC), a study published in June 2021 found that seropositivity to the COVID-19 spike protein (due to infection) does not prevent embryo implantation or early pregnancy development. The study used in vitro fertilization frozen embryo transfer as a model for evaluating the impact of COVID-19 seropositivity on implantation.

General Pregnancy-Specific Data

Symptoms

Pregnant women experience the same symptoms as the general population, and may even be largely asymptomatic. Symptoms include shortness of breath, fever, fatigue, chills, muscle aches, and cough. Infection appears to significantly more common in the third trimester, but this may be due to universal testing as women are admitted for labor and delivery.

Regardless of severity, pregnant women may experience a longer duration of symptoms, as at least one study indicated some COVID-19 positive pregnant women experienced symptoms eight weeks or longer after diagnosis (but many others have no symptoms).

Infection Severity and Risk

Overall, when compared to the non-pregnant population, pregnant women with COVID-19 appear to have an increased risk of hospitalization, bleeding, preeclampsia, ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, and the use of ECMO, as well as death (especially in the third trimester). While overall risk remains low, "pregnancy is an independent risk factor for respiratory (breathing) deterioration in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2".

A study published in February 2022, using data from 17 US hospitals, found that pregnant and postpartum women with COVID-19 were at "significantly increased risk of a composite of death and serious obstetric morbidity related to hypertensive disorders of pregnancy [high blood pressure], postpartum hemorrhage, and infections" when compared with individuals without COVID-19 infection. Additionally, a study published in October 2022 corroborated the risk of high blood pressure related to COVID-19 infection in pregnancy.

A November 2020 study of 252 pregnant women who tested positive for COVID-19 indicated that approximately 5% of all pregnant women with COVID-19 infection develop severe or critical illness. A separate study from July 2021 of 926 pregnant women indicated this risk appeared to be around 13%. According to the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine as of November 2021, overall low absolute risks appear to be: 2.9 per 1,000 for invasive ventilation, 0.7 per 1,000 for ECMO, and 1.5 per 1,000 for death.

Across numerous studies, pre-existing conditions consistently play a role in disease severity, such as obesity, older maternal age, hypertension, diabetes, and asthma. Black and Hispanic pregnant women also appear more likely to experience severe infection and hospitalization.

In general, the increase in progesterone in pregnancy causes the nasal capillaries, nasal mucus membranes, and upper respiratory tract to swell; this helps viruses attach and makes it harder for immune cells in the nasal cavity to kill these pathogens.

Further, along with upper respiratory tract swelling, lung expansion is restricted as the uterus enlarges; this can lead to a greater need for intensive care and mechanical ventilation during pregnancy due to severe respiratory virus infection.

Stage of pregnancy may also be a factor, similar to influenza, although data is limited. COVID-19 is a pro-inflammatory virus that causes severe and excessive inflammation throughout the entire body. Early pregnancy and near term (third trimester) are considered pro-inflammatory, which could make COVID-19 infection more severe at these stages, but more research is necessary. Currently, it appears that third trimester may be the riskiest time period for infection.

Blood clot (and/or bleeding) risk remains inconclusive, but this appears to be uncommon (despite pregnancy itself increasing the risk of blood clots). A study published in July 2021 indicated that COVID-19 infection can be complicated by coagulopathy (excessive bleeding or clotting), featuring blood clots and other thrombosis events, which has been termed "COVID-19 associated coagulopathy" (CAC). Data concerning CAC in pregnancy is limited, but:

The study above determined that of 1,546 COVID-19 positive pregnancies, 1% developed CAC, indicating CAC appears to be uncommon in pregnancy. The authors noted that urgent research is required to determine appropriate anticoagulant dosing and duration in pregnant women with COVID-19 infection.

A study published in February 2022 indicated COVID-19 positive pregnant women may be at higher risk of bleeding-related complications during pregnancy. "These findings may reflect effects of the virus on maternal physiology that increase risk of postpartum hemorrhage."

Although most studies to date have indicated pregnant women are not more susceptible to infection than the non-pregnant population, a February 2021 study determined the COVID-19 infection rate in pregnant women in Washington State was 70% higher than similarly aged adults, which could not be completely explained by universal screening at delivery.

Although risk of preterm delivery remains inconsistent, reports finding an association are becoming more frequent. Preterm birth might be caused by changes in the placental circulation induced by the virus that results in fetal distress (and a lack of oxygen, triggering contractions). However, in some reports, cesarean section was performed to improve the mother’s condition, the baby’s condition, or was triggered for other reasons that may not have been related to infection.

According to a November 2020 CDC report, among 3,912 infants born to women with COVID-19, 12.9% were preterm, which is higher than the national estimate of 10.2%. Among 610 of those infants with testing results, 16 were positive for COVID-19, primarily those born to women with infection at delivery. Eight of those 16 infants were born preterm.

In a large population-based study published in July 2021, COVID-19 diagnosis increased the risk of preterm birth, particularly among those with medical comorbidities. (If the mother's condition deteriorates, preterm delivery is often recommended.)

There is also informal and anecdotal reporting of a lack of preterm deliveries overall during the pandemic. This phenomenon could be due to women resting more, staying at home, having more familial support, or lack of infections in general, not just COVID-19 (infection is a primary cause of preterm birth). There may also be a decrease in preterm induction, usually indicated by HCPs for medical reasons.

Despite a possible increased risk of preterm birth, a study published in April 2021 identified no significant differences in abnormal fetal ultrasound and Doppler findings observed between pregnant women who were positive for COVID-19 and controls.

Specific Variants and Pregnancy

Certain variants (Alpha, Delta) appear to increase the risk of severe outcomes in pregnancy compared to the original strain (wildtype) and the most recent, Omicron. As of October 2022, there have been several major variant waves: Alpha B.1.1.7, Beta B.1.351, Gamma P.1, Delta B.1.617.2, and Omicron B.1.1.529.

Omicron: The newest variant, omicron, is associated with less severe symptoms than the delta variant, but is highly infectious and can cause adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes especially in the unvaccinated.

According to a study published in October 2022, between May 17, 2021, and Jan 31, 2022, there were 9,923 COVID-19 infections in 9,823 pregnancies, in 9,817 women in Scotland. In this cohort, pregnant women infected with COVID-19 were substantially less likely to have a preterm birth or maternal critical care admission during the omicron-dominant period than during the delta-dominant period.

A separate study published in August 2022 found fewer cases of severe–critical disease (1.8% Omicron vs 13.3% pre-Delta and 24.1% Delta) and adverse perinatal outcomes during the Omicron wave compared with the pre-Delta and Delta waves.

Delta: To date, Delta has been the most severe wave, and caused the highest risk for pregnant women. A retrospective study published in May 2022 found that Delta was associated with increased COVID-19 severity among pregnant women compared with previous variants, which was corroborated by three additional studies.

Further, according to a study published in July 2021, of 3371 pregnant women, the proportion that experienced moderate to severe infection significantly increased between the original strain and Alpha periods, and between Alpha and Delta periods. Symptomatic women admitted in the Alpha period were more likely to require respiratory support, have pneumonia, and be admitted to intensive care. Women admitted during the Delta period had further increased risk of pneumonia. This was corroborated by a separate study published in September 2021.

Infection Transmission to Fetus/Newborn

In general, vertical transmission of any virus from the mother to fetus is not well understood, but can occur through amniotic fluid, placental transfer, umbilical cord blood, or vaginal delivery.

Note: Maternal and fetal blood never directly mix during pregnancy; this exchange takes place in the placenta.

COVID-19 and the Placenta

As of October 2022, it does not appear that COVID-19 readily crosses the placenta (although it can affect the placenta), enters amniotic fluid or umbilical cord blood, or transfers to the newborn via vaginal delivery (which does occur with other viruses). Further, neonates born to mothers who tested positive for COVID-19 appear to remain relatively healthy (and may receive their mother's COVID-19 antibodies). However:

As of October 2022, COVID-19's ability to infect the placenta is well-established. COVID-19 is theorized to harm the placenta due to the placenta's expression of ACE2 receptors, which the virus uses to infect cells. However, this occurrence appears to vary widely among individuals. Gestational age at exposure may also be an important factor determining how the placenta responds to maternal infection.

According to an October 2022 research article, multiple global studies have found that the placental pathology findings present in cases of stillbirth consist of a combination of concurrent destructive findings. These pathological lesions, collectively termed SARS-CoV-2 placentitis, can affect greater than 75% of the placenta, effectively rendering the placenta incapable of performing its function of oxygenating the fetus. Further, placental infection and destruction can occur in the absence of fetal infection.

COVID-19 Placentitis: Overall, while evidence indicates COVID-19 infection during pregnancy can cause placental damage which could lead to severe adverse neonatal outcomes (including stillbirth), but this does not appear to be common.

In April 2021, the Faculty of Pathology and Institute of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Ireland confirmed there were 6 cases of stillbirth and one case of second trimester miscarriage caused by COVID-19 placentitis (infection of the placenta) since January 2021. The statement added there appeared to be a link with the B.1.1.7 (Alpha) variant which could explain why this finding was not a significant feature of the first two waves of the pandemic.

A study published in February 2022 evaluated the role of the placenta in causing stillbirth and neonatal death following maternal infection with COVID-19. All 68 of the examined placentas had findings consistent with COVID-19 placentitis, which may have lead to fetal demise due to a lack of oxygen to the fetus.

In contrast, a separate study from 2020 examined twenty-one third trimester placentas of women who tested positive for COVID-19 and did not find any major adverse effects on placental structure and pathology, and another study from December 2020 identified no placental or fetal transfer of the virus.

Further, some findings have determined that even if placental damage is identified, it may not always lead to adverse outcomes. Two studies published in May and August 2021 found that even when histopathological findings suggested placental damage, these babies appeared to be born relatively healthy.

A separate study from July 2020 examined sixteen placentas from COVID-19 infected women. Third trimester placentas were more likely to reflect a systemic inflammatory or hypercoagulable state (tendency for blood to clot). Despite these changes, all newborns tested negative for the virus and were discharged within four days.

A study published in February 2022 indicated the COVID-19 virus rarely persists in the placenta up to four months after diagnosis. Further, placental antiviral response remains active for weeks to months after COVID-19.

However, despite this inconsistency regarding placental infection/damage, neonates have tested positive for the virus within 30 minutes of delivery, and the virus has been identified in amniotic fluid. But overall, this appears to be rare and likely depends on severity of infection, stage of pregnancy, and how long the fetus is exposed to the virus (i.e. time of infection in the mother to time of delivery).

Further, despite its rarity, recent studies have shown transmission can occur at all stages of pregnancy.

In a study published in September 2022, researchers detected COVID-19 in syncytiotrophoblast tissue (part of the placenta that is between maternal and fetal blood) and fetal tissue between weeks 8 and 12 of pregnancy. The results suggest that COVID-19 vertical transmission is indeed possible during the first trimester, even in pregnant women with no symptoms (but is still rare).

A study published in August 2022, COVID-19 RNAs or Spike protein was detected in the stool of 11 out of 14 preterm newborns born to mothers with resolved COVID-19 weeks prior to delivery despite negative newborn nasal PCR swabs. These findings suggest risk of in utero COVID-19 transmission to the fetal intestine during pregnancy.

A study published in September 2021 included 42 pregnant women who tested positive via nasopharyngeal test at 24-48 hours before delivery. All women were asymptomatic at the time of the test, but approximately 59% developed mild disease after delivery. Newborns were tested immediately at birth and at 24 hours. There were five cases of intrauterine transmission of COVID-19.

According to a study published in May 2021, among 1448 newborns who underwent PCR testing, fifty-nine (4%) were PCR-positive. Neonates testing positive were born to both symptomatic and asymptomatic women, and nearly all were born to women with infection identified near delivery.

Stillbirths have been documented from severe infection, and in all trimesters. Overall, data regarding risk of stillbirth and COVID-19 are inconsistent, but it does appear to be rare. Further, in at least one study that indicated an increased risk, this increase was thought to be due to factors other than COVID-19 infection (more in Prenatal Care/Appointments).

Therefore, it is likely (although rare) that vertical transmission could happen during any trimester but additional research and clarification between COVID-19 positive newborns and timing of infection in the mother is necessary.

Regarding the postpartum period, transmission can occur from the mother to the newborn. According to a U.K. study of 66 newborns who tested positive for COVID-19, 17 were suspected of contracting the infection from their mother after delivery.

The authors indicated that despite these numbers, the newborns did not experience severe illness, and the benefits of remaining with the mother after delivery appear to outweigh the possibility of infection. Symptoms in these newborns included high temperature, poor feeding, vomiting, a runny nose, cough and lethargy.

Long-term outcomes: A study published in July 2021 found that there was no difference in growth, neurodevelopment, and hospital readmission at 6-months of age between infected and non-infected babies born to COVID-19 positive mothers.

In contrast, a study published in May 2022 found that "Infants prenatally exposed to [COVID-19] appear to have a risk of developing along a spectrum from possible serious neurological disorders to minor neurological disorders to a less-than-perfect optimal performance, which should be confirmed in follow-up research. Timely implementation of follow-up programs for infants exposed to SARS-CoV-2 prenatally is urgently needed to identify children at risk."

Testing

According to the CDC, there are two types of tests (decisions about testing are made by state or local health departments or healthcare professionals).

A viral test is used to test for current infection. Two types of viral tests can be used: nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) and antigen tests.

An antibody test (also known as a serology test) can detect a past infection. Antibody tests should not be used to diagnose a current infection.

At home testing: Several different brands of "home" FDA-authorized COVID-19 tests are available that can be purchased online or from a retailer. These tests allow rapid results (RT-PCR should be used to confirm). According to the CDC, individuals should read the complete manufacturer’s instructions for use before using the test and talk to their health care provider if they have any questions.

The most reliable test for current infection is the RT-PCR (real time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, a type of NAAT). This type of test is used to identify the genetic material of a virus (see Resources). Specimens are collected from the patient’s nose or throat using nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swabs.

It is often recommended that if the first test is negative, but the disease is highly suspected, a second test should be performed. A negative result can be confirmed through two negative tests in a row, spaced at least 24 hours apart.

In suspected serious cases, HCPs may also use a chest CT scan for diagnosis, as this has been reported to be superior in early diagnosis compared with RT-PCR. The CT can show what is called “ground glass”, or white spots on the lungs that indicate the infection is present. For pregnant women, the diagnostic value of the CT may outweigh possible radiation risk to the fetus (read Radiation).

Women should have a risks and benefits conversation with their HCP regarding any imaging scans during pregnancy.

Some health care facilities may universally test all pregnant women prior to delivery, as pregnant women can also be asymptomatic, similar to non-pregnant individuals.

Management and Treatment

Overall: There is no definitive treatment regimen for pregnant women with COVID-19; therefore, all management is currently individualized based on disease severity, stage of pregnancy, and risks and benefits of any medications.

It is also recommended that every pregnant woman with COVID-19 be monitored carefully due to possible complications, even if a woman initially presents without symptoms.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) have developed an algorithm to aid practitioners in assessing and managing pregnant women with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 (read more).

Formally, and depending on severity, recommendations include isolation, infection control procedures, diagnostic testing, possible antiviral medications or monoclonal antibody treatment, oxygen therapy if needed, antibiotics (secondary bacterial infection risk), fetal and uterine contraction monitoring, and an individualized delivery plan.

Antiviral Medications: As of December 23, 2021, there are two antiviral drugs under U.S. FDA emergency use authorization: nirmatrelvir and ritonavir (Paxlovid; combination medication) and molnupiravir (Lagevrio):

Nirmatrelvir and ritonavir (Paxlovid): On December 22, 2021, the FDA gave emergency authorization for this antiviral medication to help prevent severe COVID-19 infection. This medication contains separate tablets of nirmatrelvir and ritonavir. Paxlovid is intended for those 12 years of age and older who test positive for COVID-19 and are at risk for severe disease.

According to Developmental and Reproductive Toxicity (DART) [animal] and human studies as of December 23, 2021:

There is no available human data on the use of nirmatrelvir during pregnancy to evaluate risk of major birth defects, miscarriage, or adverse maternal or fetal outcomes.

Reduced fetal body weights following oral administration of nirmatrelvir were observed at exposures approximately 10 times higher than clinical exposure at authorized human dose.

No other adverse developmental outcomes were observed with nirmatrelvir at exposures greater than or equal to 3 times higher than the authorized human dose.

Limited studies on ritonavir use during pregnancy in humans have not identified an increase in the risk of major birth defects.

Published studies with ritonavir are insufficient to identify a drug-associated risk of miscarriage.

In animal reproduction studies with ritonavir, no evidence of adverse developmental outcomes was observed following oral administration of ritonavir at doses greater than or equal to 3 times higher than authorized human dose.

Lactation: There are no available data on the presence of nirmatrelvir in human or animal milk, the effects on the breastfed infant, or the effects on milk production.

A transient decrease in body weight was observed in the nursing offspring after maternal administration of nirmatrelvir (8x higher than human dose).

Limited published data reports that ritonavir is present in human milk. There is no information on the effects of ritonavir on the breastfed infant or the effects of the drug on milk production.

Organizational recommendations on Paxlovid:

On December 22, 2021, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (United States) released a statement supporting "the use of Paxlovid...for treatment of pregnant patients with COVID-19 who meet clinical qualifications. Any therapy that would otherwise be given should not be withheld specifically due to pregnancy or lactation.”

On December 22, 2021 the European Medicines Agency advised against the use of Paxlovid during pregnancy and that breastfeeding should be interrupted during treatment. "These recommendations are because laboratory studies in animals suggest that high doses of Paxlovid may impact the growth of the foetus...[and] a risk to the newborn/infant cannot be excluded. "

Important consideration as noted by the FDA: "COVID-19 in pregnancy is associated with adverse maternal and fetal outcomes, including preeclampsia, eclampsia, preterm birth, premature rupture of membranes, venous thromboembolic disease, and fetal death" [risk vs. benefit].

Molnupiravir (Lagevrio): On December 23, 2021, the FDA gave emergency use authorization for this antiviral medication to help prevent severe COVID-19 infection in those considered high risk. Molnupiravir is intended for those 18 years of age and older who are at high risk of severe covid-19 disease and “for whom alternative COVID-19 treatment options authorized by the FDA are not accessible or clinically appropriate.”

Molnupiravir is currently NOT recommended in pregnancy or while breastfeeding.

According to the FDA fact sheet: "Molnupiravir may cause harm to your unborn baby. It is not known if molnupiravir will harm your baby if you take molnupiravir during pregnancy...When molnupiravir was given to pregnant animals, molnupiravir caused harm to their unborn babies."

"You and your healthcare provider may decide that you should take molnupiravir during pregnancy if there are no other COVID-19 treatment options authorized by the FDA that are accessible or clinically appropriate for you. If you and your healthcare provider decide that you should take molnupiravir during pregnancy, you and your healthcare provider should discuss the known and potential benefits and the potential risks of taking molnupiravir during pregnancy."

"Breastfeeding is not recommended during treatment with molnupiravir and for 4 days after the last dose of molnupiravir. If you are breastfeeding or plan to breastfeed, talk to your healthcare provider about your options and specific situation before taking molnupiravir."

Additional medications:

Medications such as Type I interferon, lopinavir, ritonavir (by itself) and tocilizumab are still being studied in the general population and are not (routinely) recommended for pregnant women; studies on safe and effective treatments for COVID-19 positive pregnant women remain ongoing.

Remdesivir is also not routinely recommended for pregnant women due to a lack of safety data as well as effectiveness. However, it may be used in severe cases under compassionate use and has been linked with initial positive results (very small case studies). Side effects of remdesivir in pregnant women may include possible liver complications.

Monoclonal antibody (mAb) treatment:

In a research letter published in October 2022, the authors describe the use of anti-spike monoclonal antibodies to treat mild to moderate COVID-19 in 47 pregnant patients. The authors found no conclusive evidence of maternal or fetal complications due to the treatment. Only two patients had progression of the disease and only one required hospitalization.

A study published in April 2022 determined that in 944 pregnant persons with COVID-19, adverse events after mAb treatment were uncommon, and there was no difference in obstetric-associated safety outcomes between mAb treatment and no treatment. MAb treatment was associated with similar 28-day risk of a COVID-19- associated outcome and more non-COVID-19-related hospital admissions compared to no mAb treatment.

A study published in April 2022 indicated that five out of seven unvaccinated pregnant women hospitalized due to COVID-19 infection improved after administration of casirivimab–imdevimab, while one patient needed ICU admittance but survived without severe complications. Treatment was well tolerated in all cases with no adverse events reported.

A separate case report was published in September 2021 of two unvaccinated pregnant individuals with moderate COVID-19, one in the second trimester and one in third trimester. They were treated with casirivimab and imdevimab. Neither experienced an adverse drug reaction, and neither progressed to severe disease.

A study published in August 2021 described successful use of of monoclonal antibody treatment for symptomatic COVID-19 in four pregnant patients. The authors found no evidence of pregnancy complications or treatment failure. All four patients avoided progression to severe disease and none required additional COVID-19 related medical visits or hospitalizations.

Blood clotting: Both pregnancy and COVID-19 are associated with an increased risk for blood clotting – to include in asymptomatic women in isolation at home. However, this is also slightly debated as not all studies have found an increased risk. Further, although case reports exists, widespread reporting of blood clotting issues from COVID-19 infection in pregnancy has not been reported.

Some guidance indicates that suspected and confirmed COVID-19 pregnant women should receive preventative low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) before and after delivery (unfractionated heparin if delivery is close). Other reviews indicate there is not enough evidence to recommend heparin, and this medication could increase the risk of bleeding.

Delivery: Since there is currently no evidence that vaginal delivery can increase the risk of vertical transmission, mode of delivery should also be individualized and depends on stage of pregnancy, health of the fetus, and the mother’s overall health.

Fetus/Newborn: Prior to delivery, it is recommended that women undergo regular fetal heart monitoring and ultrasounds to monitor growth. Steroids may be considered for fetal lung maturation, depending on gestational age and severity of the mother’s disease.

After delivery, guidelines also conflict on whether the newborn should be separated from the (infected) mother to prevent infection transmission. However, most obstetric organizations agree the benefits of the mother and baby being together outweigh the possible risks of transmission. Women and their HCPs should have individualized discussions regarding infant separation for mothers suspected or confirmed to have COVID-19.

Antibody Transfer to Fetus after Infection (via Placenta and/or Breast Milk)

Updated September 2022: Current data on COVID-19 antibody transfer to the fetus/newborn after maternal infection during pregnancy:

All types of COVID-19 infections – asymptomatic, mild, severe –initiate antibody transfer across the placenta.

Antibody levels from mild COVID-19 infection during pregnancy appear to decline more quickly than after severe infection (may be faster decline for asymptomatic, but this has not been studied).

A longer interval between infection and delivery provides more time for effective transplacental transfer of antibodies (e.g. two months better than two weeks; also likely depends on severity of infection).

However, infection in early pregnancy may not provide lasting antibody protection to fetus/newborn (vs. infection in late pregnancy) as this interval could be too long.

Antibody levels passed to a newborn after COVID-19 infection during pregnancy have been shown to decline in infants approximately 6 to 11 weeks after birth.

Despite this decline, passive immunity may persist in infants up to six months of life.

Infection in early to mid-pregnancy + vaccination later in pregnancy appears to be safe and produces strong antibody transfer across the placenta (and is recommended).

COVID-19 infection during pregnancy also transfers antibodies to colostrum and breastmilk; these antibodies are effective at neutralizing the virus.

Of note, it is currently unclear how long this lasts, but at least one study indicated antibodies were present in breast milk up to 10 months after a positive COVID-19 test. However, this amount and level of protection is likely highly variable, depending on stage of pregnancy during infection, severity of infection, whether the infant is exclusively breastfed, and length of time the infant is breastfed.

Timing: A study published in November 2021 determined that, after infection, pregnant women have COVID-19 antibodies around 8 to 16 days after confirmed infection. However, the presence of cord blood antibodies took about 26 days.

Long-COVID

It is possible to experience prolonged symptoms after COVID-19 infection in pregnancy, especially after severe illness. Note: There is currently no universally accepted definition of Long-COVID (also known as post-COVID, or postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection [PASC]), but it is currently described (in brief) as a wide range of symptoms that last longer than four weeks. These symptoms can be persistent from the original infection, appear after initial recovery, or may occur as a result of hospitalization or treatment.

In general, non-pregnant women appear to have an increased risk of Long-COVID over men, but it is not currently known if this increased risk is higher or lower in the setting of pregnancy.

For those pregnant and breastfeeding, there has been a limited number of papers published that have investigated Long-COVID symptoms in women who had COVID-19 in pregnancy. However, although limited, these preliminary findings indicate that some pregnant women may experience a prolonged and persistent level of fatigue after infection; but larger, more well-designed studies are necessary to determine the risk of Long-COVID after COVID-19 infection in pregnancy.

Current studies:

October 17, 2022: While this study did not primarily assess for Long-COVID, researchers recruited 84 pregnant women with mild COVID-19 and 88 pregnant women without COVID-19. All participants were unvaccinated. Of the 83 participants who attended the follow-up for post-COVID-19 symptoms, 63 of them (75.9%) presented with Long-COVID, with the most common symptoms being shortness of breath, fatigue, headache, and loss of taste and/or smell. The median duration of long COVID symptoms was 60 days.

June 2022: This study (pre-print) investigated the prevalence and persistence of post-viral fatigue after a diagnosis of COVID-19 infection during pregnancy or at delivery among nearly 600 participants. First, the prevalence of overall fatigue following COVID-19 was significantly higher compared to groups that had a positive test at delivery, but no evidence of infection during pregnancy or negative test at delivery and in subsequent follow-ups. Second, approximately a quarter of pregnant women with COVID-19 during pregnancy presented fatigue six months after infection. Third, the risk of fatigue increased with the severity of the acute infection during pregnancy with 2.4-fold increased risk in women with severe disease compared to mild disease.

January 2022: All women requiring intensive care treatment for COVID-19 in this registry were included and compared regarding maternal characteristics, course of disease, as well as maternal and neonatal outcomes: Of 2650 cases in the registry, 101 women (4%) had a documented ICU stay. COVID-19 was diagnosed at a median gestational age of 33 weeks. Follow up visits were completed for 47 of the 101 women at a median of 8 weeks after childbirth. 12 women reported a variety of post-COVID symptoms, i.e., impairment of daily life activities and problems due to thromboembolic events, tachycardia, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

December 2020: This paper reported the results of an ongoing Clinical Trial (NCT04323839) of women in the United States who are pregnant or up to 6 weeks postpartum with known or suspected COVID-19 infection. This study analyzed the clinical presentation and disease course of COVID-19 in participants who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection and reported symptoms at the time of testing. Of 991 participants enrolled from March 22, 2020, until July 10, 2020, the median time to symptom resolution was 37 days (95% CI 35-39). One quarter (25%) of participants who tested positive for COVID-19 infection had persistent symptoms 8 or more weeks after symptom onset.

The National Institutes of Health is currently conducting a four-year follow-up study on the potential long-term effects of COVID-19 on women infected with SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy. Researchers hope to understand what proportion of patients with COVID-19 in pregnancy are at risk for Long-COVID and whether the severity of infection in pregnancy influences the likelihood of developing Long-COVID.

Prenatal Care/Appointments

Women who attend their prenatal appointments should be assessed for fever each time and evaluated for signs and symptoms of a respiratory infection.

Women need to express any concerns they have with their HCP, to include their appointment schedule (virtual or in person), fetal monitoring, what they should do in-between appointments if they suspect infection, and what to do if they experience contractions, especially if nearby hospitals have changed their procedures.

Women should continue to see their HCP when recommended, or when they feel they may be experiencing a concern.

At least one study noted an increase in the stillbirth rate in one U.K. hospital during the pandemic. Of note, none of the stillbirths were indicated in women who tested positive for COVID-19. This indicates that a decrease in appointments, prenatal care, routine screenings, or ultrasounds may have occurred that led to this increase. (Note: Other facilities have noticed a decrease in stillbiths.)

Women also need to tell their HCP how they are coping with the pandemic. Increasing isolation, preventative measures, anxiety about their health and the health of their baby, and a significant amount of uncertainty can increase women’s risk for depression and anxiety during pregnancy and the postpartum period.

Pregnant women and those trying to conceive should also consider being vaccinated against COVID-19, although this is a completely personal choice.

Action

The best way to prevent the virus is to avoid being exposed and to get vaccinated.

Pregnant woman should also:

Seek care immediately if experiencing a medical emergency. Emergency symptoms can include trouble breathing, persistent pain or pressure in the chest, new confusion, inability to wake or stay awake, or bluish lips or face. This is not an inclusive list, and women should always call their HCP or visit an emergency room when necessary.

Report any and all symptoms of a respiratory infection to their HCP, to include cough, fever, shortness of breath, and diarrhea

Avoid unnecessary traveling, use of public transportation, and contact with sick people

Wear a mask (to protect others) in public settings

Quit smoking (risk factor for infection)

Follow personal and social distancing rules

Regularly wash hands for at least 20 seconds (if soap and water are not readily available, use a hand sanitizer that contains at least 60% alcohol)

Avoid touching their eyes, nose, and mouth with unwashed hands.

Do not skip prenatal care appointments or other health appointments that may be necessary

Tell their HCP if they get tested in a location other than their HCP's office

Make sure to have at least a 30-day supply of prescription medications

Learn about stress and coping

Get adequate sleep and physical exercise

Go outside in open areas for walks, fresh air, and a change of scenery

Any pregnant woman who has traveled in a state or country with a high rate of COVID-19 infection or who has had close contact with an individual with confirmed infection should be tested and quarantined.

Women should refer to the CDC and ACOG COVID-19 web pages below for additional information (see Resources).

Partners/Support

Partners, family members, and other adult family members who live with a pregnant woman need to practice the same hygiene and social distancing habits and procedures as they do.

This includes maintaining a distance of at least 6 feet from other individuals, wearing a mask in public settings, washing hands for at least 20 seconds, and regularly disinfecting commonly touched surfaces in the office or at home.

Household transmission of COVID-19 is common and occurs early after illness onset.

CDC advises that persons should self-isolate immediately at the onset of COVID-like symptoms, at the time of testing as a result of a high risk exposure, or at time of a positive test result, whichever comes first.

All household members, including the infected person case, should wear masks within shared spaces in the household.

Symptoms can include:

Fever or chills

Cough

Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing

Fatigue

Muscle or body aches

Headache

New loss of taste or smell

Sore throat

Congestion or runny nose

Nausea or vomiting

Diarrhea

Emergency symptoms can include trouble breathing, persistent pain or pressure in the chest, new confusion, inability to wake or stay awake, or bluish lips or face. This is not an inclusive list, and individuals should always call their HCP or visit an emergency room when necessary.

Infected persons should also:

Get vaccinated. (Vaccination does not cause "shedding". Learn more.)

Stay home. Most people with COVID-19 have mild illness and can recover at home without medical care. Individuals should remain at home unless they need to seek medical care.

Get rest and stay hydrated.

Stay in touch with an HCP and seek emergency medical care for difficulty breathing.

Individuals should refer to the CDC COVID-19 page for additional detailed information and resources.

Resources

Total cases in the United States/COVID tracker (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

COVID-19 Home Page (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

COVID-19 Testing Page (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

Management Considerations for Pregnant Patients With COVID-19 (Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine)

How does the RT-PCR test work? (International Atomic Energy Agency)

Novel Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19): Practice Advisory (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; December 2020)

Management Algorithm (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine)

COVID-19 FAQs for Obstetrician-Gynecologists, Obstetrics (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists)