Stages of Labor

The process of labor and delivery is split into four stages (previously three) which include the start of labor to full dilation, pushing to delivery, removal of the placenta, and postpartum recovery.

Learning about the stages of labor can help women understand the process and when different interventions may take place. This helps women recognize when and why certain options are available, and the most important steps in the overall timeline of vaginal delivery.

HCPs can determine at any stage of labor that oxytocin, amniotomy, assisted delivery, or cesarean section may be necessary. All scenarios should be discussed thoroughly between a woman and her HCP, and women should not be afraid to ask their HCPs what and why certain actions are taking place and what options additional options are available.

Background

Graphic warning: A photograph of a real placenta is in the "Third Stage: Placental Removal" section.

Labor has been traditionally divided into three stages, but more modern assessments believe it should be divided into four stages, with postpartum recovery as an added stage:

First Stage: Dilation – 0 to 10 centimeters (cm)

Second Stage: Pushing to delivery

Third Stage: Removal of the placenta

Fourth Stage: Postpartum/Immediate Recovery

First Stage: Early to Active Labor

Read about the physiological start of labor here.

The first stage of labor involves the cervix effacing to 100% and dilating to 10 cm.

Early contractions are relatively painless at first, but gradually build in intensity, starting at the top of the uterus and radiating through the abdomen and lower back, in which the abdomen becomes hard to the touch. This tightening does the reverse for the cervix and lower portion of the uterus, which stretches and relaxes.

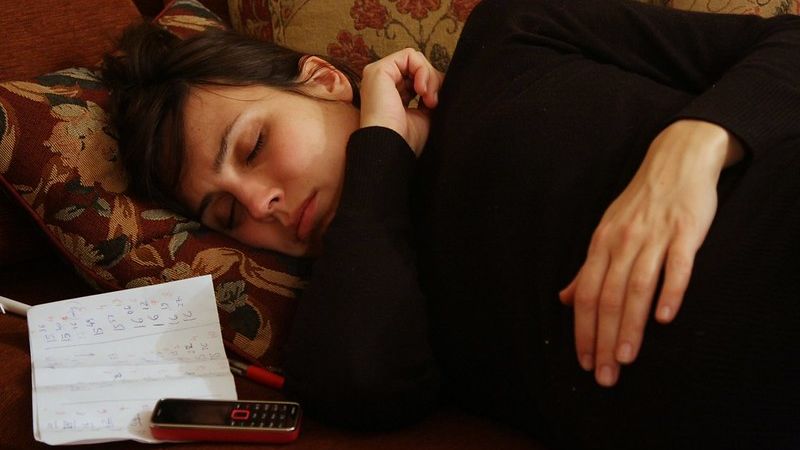

Once early labor begins (generally 1 to 3 or 4 cm), it is routinely advised that women rest at home until contractions are about 5 to 10 minutes apart. Although most sources indicate women can tell when to go to the hospital by how much more painful contractions are getting, it is also possible to tolerate or expect a higher level of pain, and therefore remain home for longer than planned. In this case, the key is in timing the contractions.

A woman should start timing contractions as soon as she feels them in order to get a baseline toward progression and note how many minutes elapse between the start of one contraction and the start of the next, and how long each one lasts.

Women may wish to eat early in the first stage, and current research indicates there is very little risk to having light foods/meals early in labor and it may help prevent a lack of energy later on (read Eating during Labor).

During the 1st stage of labor and at admission, maternal heart rate, blood pressure, and fetal heart rate are monitored, either intermittently (low-risk) or continuously (high-risk).

Women dilate at varying rates, and the time it takes to reach full dilation is dependent on several factors (read Dilation and Effacement).

If a woman has not noticed the expulsion of the mucus plug prior to contractions beginning, it may be noticed at any point during early labor. Not all women will notice it, however, as some women can lose the plug gradually.

Women may also be offered a membrane sweep early in labor, to help speed up progress (optional).

During the active phase, which can begin around 4 to 6 cm of dilation, the cervix will progress faster to full dilation, and the presenting part of the baby (usually the head) descends well into the pelvis.

During this phase, women may request an epidural and her membranes may rupture (“water will break”).

It is also possible that labor can slow down or stall at this point. There are several methods HCPs can attempt to aid in the prevention of a cesarean section, such as amniotomy or oxytocin.

First Stage: Transition

The time frame between 7 and 10 cm is commonly known as the “transition” phase of the first stage of labor.

In women experiencing their first delivery, the baby’s head typically descends slowly and gradually. The baby can descend very rapidly in subsequent pregnancies.

Nausea, vomiting, and shaking during labor can occur (but not always) during this phase, which is described as the most painful part of labor, as the body starts to change from dilation to getting ready to push.

Antiemetics, which are anti-nausea medications, are very effective and can be given to women who feel nauseous during labor.

This phase, on average, may only last 4 to 5 contractions in most women, although it could last longer in others (epidural use may affect the speed of this phase). This phase is usually easily recognized by HCPs and they will likely begin preparing for delivery.

The first stage of labor ends when the cervix is fully dilated.

*At any point during this stage, an HCP may determine that a cesarean section is necessary. Women should read about the risks and benefits of a cesarean section as well as the procedure itself to be fully prepared and informed regarding this possibility.

Second Stage: Pushing to Delivery

The beginning of the second stage is usually dependent on the HCP determining a woman is fully dilated through vaginal examination. HCPs may be coming in and out of the room to assess dilation, or may remain in the room if they notice a woman is in the transition phase.

During this stage, the cervix is fully dilated, and the woman can begin pushing. This stage can last anywhere for a few minutes to a few hours and depends on the number of prior deliveries, size of the baby, position of the baby, the mother’s exhaustion level, contraction intensity, and the use of pain medication as well as other factors.

This image contains triggers for: Blood, Real Delivery

You control trigger warnings in your account settings.

This stage can be prolonged in some women. The woman could be tired, the baby could be in the wrong position, an epidural could make it hard to push, the baby could be too big, or the woman could be experiencing an ineffective pattern of contractions. HCPs have several options when this occurs to avoid a cesarean delivery.

Oxytocin can be used to augment labor and help with contraction pattern.

Assisted delivery (forceps/vacuum) may also be used, either to turn the baby's head or help the baby further down the birth canal. The main goal of assisted delivery is to prevent a cesarean section.

An episiotomy is only necessary in very limited circumstances during labor (read Tearing and Episiotomy), usually if the baby needs to come out as soon possible.

An HCP may also determine a cesarean section is necessary at any point during this stage, especially if the mother, baby, or both are in distress.

As the baby comes further down through the vagina, the woman will likely feel pressure through the rectum as well as the urge to push (for information on “pooping” during labor, click here). When the widest part of the baby’s head can be seen at the vaginal opening and remains there in between contractions, this is known as crowning.

Once the head is out, the baby can be delivered with only 1 or 2 additional pushes. Most often, the shoulders appear at the vulva just after external rotation and are born easily. The HCP will then grasp the sides of the head and use gentle downward traction then an upward movement to assist delivery of the second shoulder; the rest of the body generally follows the shoulders.

When the baby is out, he/she will be placed on the woman’s chest and the umbilical cord will be clamped and cut.

Third Stage: Placenta Removal

The third stage of labor includes the removal of the placenta.

After the baby is delivered, additional, milder contractions begin about 5 to 10 minutes later. These contractions constrict the spiral arteries that supply the placenta with blood, which prevents hemorrhaging and encourages the placenta to dislodge.

When the top of the uterus suddenly sinks down to the level of the belly button after delivery, this decreases its surface area and the placenta thickens to accommodate this change; then it "buckles". This tension pulls the placenta from the uterine lining and the cord stops pulsating. With the increased abdominal pressure (from contractions), this causes the placenta to slip out of the vagina.

This image contains triggers for: Blood, Internal Anatomy, Real Delivery

You control trigger warnings in your account settings.

There are two forms of placental removal; active or expectant management. Expectant management allows the placenta to dislodge naturally with "no intervention"; it is expected this should occur within 30 to 60 minutes.

Women may be encouraged to breastfeed if possible, which releases oxytocin and causes contractions. Even with delayed cord clamping, the typical umbilical cord is long enough to allow the mother to breastfeed the baby.

Active management is a common practice which may reduce excessive blood loss and infection risk by removing the placenta more quickly than expectant management. Removal of the placenta under active management could be as quick as 5 to 10 minutes but may take up to 30 minutes. After the cord is clamped and cut, the HCP may administer oxytocin and/or manually massage the uterus, then carefully tug (not pull) on the cord to speed up its removal. The HCP may also ask the woman to bear down or push slightly.

If a woman chooses expectant management but does not deliver the placenta within 30 to 60 minutes, the HCP may move to active management, as the risk of hemorrhage is increased due to placental retention.

The placenta could also be trapped by the cervix or remain attached to the uterine lining. If it is loosely attached this is known as adherent placenta. If it is deeply attached, this is known as placenta acreta. A retained placenta can cause severe infection or life-threatening blood loss if left untreated.

If all attempts to remove the placenta are unsuccessful, the placenta will need to be manually removed under regional or general anesthesia (or more medicine if an epidural has already been placed). Antibiotics will also be administered to prevent infection.

Manual removal is completed with the HCP palpating the uterus over the woman’s abdomen with one hand, and inserting the other hand into the uterus, guided by the umbilical cord. Using the cord, HCPs can feel for the placenta and dislodge it from the uterus. If manual removal is unsuccessful, surgery is necessary.

After removal, the HCP examines the placenta and umbilical cord (size, shape, consistency, completeness, irregularities) to make sure it is intact as any part of the placenta that remains in the uterus could cause excessive bleeding and infection.

Fourth Stage: Recovery

A fourth stage is sometimes added, termed “immediate postpartum care". This stage represents the period of a few hours after expulsion of the placenta when close observation is desirable to avoid or detect postpartum hemorrhage, signs of sepsis or hypertension, to assist in breastfeeding initiation, and assess the overall health of both mother and baby.

Woman may remain the hospital for up to 2 days after a vaginal delivery, but may remain up to 4 days after a cesarean section. Mom and baby are checked often, a pediatrician will assess the baby, and women are encouraged to become ambulatory (walk around), shower, and eat and drink to speed up the recovery process.

While some women will likely remain in the same room in which they delivered, other women will be moved to a postpartum recovery room a few hours after delivery (same with cesarean section).

Action

Women should ask their HCP any questions or concerns they have regarding the labor, delivery, and recovery process. Midwives, labor and delivery nurses, and doulas are also excellent resources who tend to have more time to discuss labor and delivery with women. Women can also take childbirth classes, either online or in person, and keep track of what aspects of labor and delivery in which they would like to have more information.

When women are better informed regarding labor and delivery, they will feel less anxious, less nervous, more in control, and are more likely to have a positive birth experience.

Resources

Stages of Labor (StatPearls/NCBI Bookshelf)

What Happens during Labour and Birth (U.K. National Health Service

Safe Prevention of the Primary Cesarean Delivery (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists)

Delivering the placenta in the third stage of labour (Cochrane Review)