Hormones

Hormones affect almost every aspect of pregnancy, from ensuring its success, to causing a limitless number of symptoms, and from initiating labor and delivery to eventually producing colostrum and breast milk.

Researchers are still learning exactly which hormones have which roles during pregnancy, what levels are normal, and how to use hormones to prevent or treat pregnancy-related complications.

Women should read more below to better understand hormones and their functions during pregnancy. This can provide a clearer view of why they may be experiencing so many different symptoms at the same time, and why these symptoms can be difficult to manage in some cases.

Background

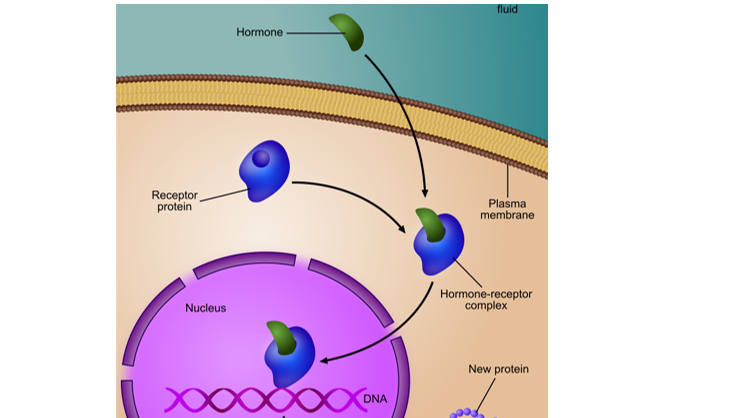

Hormones are part of the body’s endocrine system. Endocrine glands – including the placenta, a major endocrine organ – produce hormones that enter the bloodstream to communicate with any organ system in which receptors for these hormones are located.

Some hormones only have receptors in a few places of the body, while others have them in many different locations throughout the body.

How they work/affect the body:

When a specific hormone “docks” to its receptor in a cell, it tells that cell to changes its function. This explains why hormones cause so many different symptoms during pregnancy, and why so many organ systems are affected.

Hormones are required to tell the body a pregnancy has occurred; these hormones tell the body it needs to change to support the pregnancy, which brings a long list of physical side effects.

For example, progesterone is needed to prevent the uterus from contracting until term. However, since the gastrointestinal system also has progesterone receptors, the GI system is also affected, even if those changes are not necessarily needed for pregnancy.

Another different example: Oxytocin receptors in the uterus increase almost 100-fold near the end of pregnancy in preparation for labor. A lack or loss of these receptors near and during labor is linked with a failure to begin or progress to delivery (i.e. the uterus is not able to “receive” the oxytocin signal).

Researchers are still learning about hormones and pregnancy; the hormones involved in reproduction were not completely identified until the 1920s and 30s.

Human Chorionic Gonadotropin

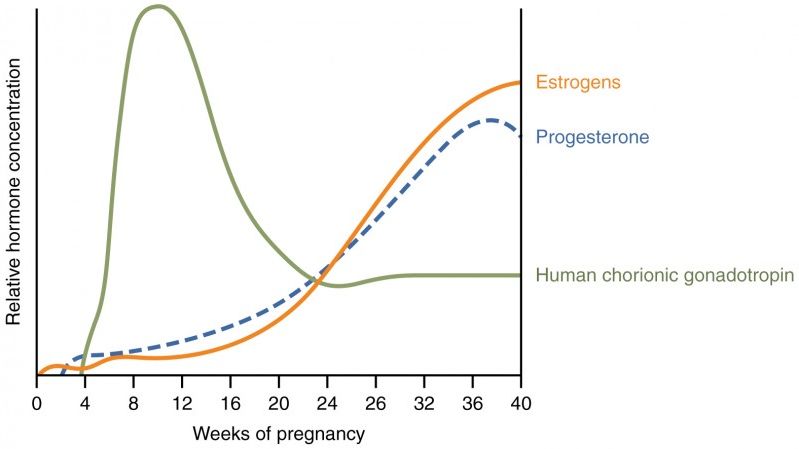

Human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) is a hormone produced by the trophoblasts of the developing placenta. After implantation, the embryo actively secretes HCG, which can be detected in the mother’s blood as early as 8 days after ovulation.

HCG is the first hormone that lets the body know a pregnancy has occurred; once this hormone is detected, the rest of the body begins changing to support the pregnancy, to include releasing additional hormones (estrogen, progesterone).

Estrogen

High levels of progesterone and estrogen are important for a healthy pregnancy. Both hormones have different roles in pregnancy and are vital for fetal growth and development, correct placental function, growth of breast tissue for lactation, and the initiation of labor.

The rate of estrogen production and the level of estrogens in the blood increase dramatically during pregnancy, although the exact increase is unknown, and normal ranges vary significantly from woman to woman. Some estimates indicate estrogens can increase 30-to 100-fold, while a 1,000-fold increase can occur with estriol, a weaker type of estrogen.

There are three types of estrogens: estrone (fairly weak), estradiol (most potent type), and estriol (weak, but produced in significant amounts during pregnancy).

Estriol is produced in high amounts at the beginning of the second trimester and continues until birth. High amounts of this hormone detected via the mother's blood or urine indicates healthy fetal liver and placental development.

Symptoms associated with estrogen include: breast tenderness, mood wings and irritability, headaches, gall bladder issues, and trouble sleeping.

Estrogen also increases toward the end of the third trimester which, along with uterine stretch, causes receptors on the uterine wall to develop and bind (natural) oxytocin (described above), which in turn causes uterine tightening and the initiation of contractions.

Progesterone

Progesterone is vital to a successful pregnancy and has been aptly named the “hormone of pregnancy".

Progesterone is first required for successful implantation and is produced by the corpus luteum after ovulation. If a pregnancy occurs, the corpus luteum will continue to produce progesterone so menstruation does not begin. If the corpus luteum fails in early pregnancy, contractions rapidly occur and implantation will be unsuccessful.

Progesterone production shifts from the corpus luteum to the placenta around 7 to 9 weeks, with full transition occurring between 10 and 12 weeks. The placenta produces this progesterone by converting cholesterol from the mother’s bloodstream.

Since the 1970s, progesterone supplementation has been given to women with no corpus luteum (or one that fails) through 10 weeks of pregnancy to maintain a pregnancy. However, while the full effectiveness, dose, and length of time necessary is still debated.

The progesterone production rate is estimated to be 250 milligrams (mg)/day in a normal pregnancy with one baby; this increases to about 600 mg/day in a multiple pregnancy. This is assessed to be a naturally stronger attempt to avoid preterm labor.

The increase in progesterone during pregnancy can cause many symptoms during pregnancy, and is commonly associated with nausea, vomiting, heartburn and acid reflux, and constipation. It is largely believed that progesterone inhibits the ability of the stomach and intestines to contract; therefore they “move” slower, and food remains in the GI tract longer.

However, even though commonly cited, evidence is inconsistent regarding GI tract motility during pregnancy, and the rate of emptying has only been partially studied. Further, some studies have noticed no change in the rate of digestion during pregnancy, except for labor. Therefore, progesterone’s role in these symptoms, especially nausea and vomiting, remains uncertain (read GI Tract Changes).

Since progesterone prevents contractions, the placenta boosts estrogen production near the end of pregnancy to overpower progesterone's effects. This change makes the uterus more sensitive to the initiation of contractions. A continued blocking (see next bullet) of progesterone allows contractions to intensify and progress to true labor; the true rate of decrease of progesterone is debated (if it decreases at all):

Several studies have found that serum (blood) levels of progesterone remain elevated throughout pregnancy to include during labor. In fact, elevated progesterone is necessary for effective labor. Therefore, it is more accurate to indicate that progesterone's uterine-calming effects are actually BLOCKED before/during labor, rather than indicating that levels drop (a receptor that blocks progesterone's actions increases in the uterus near term, blocking its effects, but not lowering its serum levels – which likely need to remain elevated).

Further, preterm labor can be prevented in some cases through the use of supplemental progesterone, and progesterone blockers (antiprogestins) are often used to induce labor, mimicking the natural process above.

Regardless of true progesterone levels, there is a change in the progesterone-estrogen ratio near term due to the significant increase in estrogen. The change may be felt by some women as Braxton Hicks contractions. However, since some women can feel these “false” contractions even before this ratio changes, this indicates other factors likely contribute to these early contractions.

Relaxin

Relaxin is believed to play a vital role in the remodeling and healing of multiple tissues of the musculoskeletal system, to include the pelvic bones and cervix, which is necessary for pregnancy, labor, and delivery.

Relaxin became of interest to researchers in the 1920s when it was noted that some unknown factor affected the connective tissue that joined the pubic bones in pregnant animals.

Since then, additional research has indicated that relaxin may also have roles in sperm motility, fertilization and implantation, uterine growth, the prevention of preterm labor, cervical ripening, and the facilitation of labor.

Relaxin is produced by the corpus luteum around six weeks of pregnancy to help loosen and expand the pelvic bones, muscles, joints, and ligaments (often leading to back and joint pain). The placenta produces lower amounts of relaxin after the corpus luteum degenerates, so blood levels of the hormone fall after the first trimester.

If a pregnant woman produces little to no relaxin (such as those with no corpus luteum), it does not appear to affect birth outcomes. It is possible that women without relaxin still get the same loosening effect from progesterone and estrogen, just to a lesser degree.

Insulin

The pancreas is a large gland behind the stomach that releases insulin to control blood sugar. When the pancreas releases insulin after a meal, it helps move glucose from the bloodstream into the body's cells, where it is used as energy.

Pregnancy causes a state of insulin resistance in almost all women:

Hormones from the placenta block the action of the mother's insulin in her body – this is normal during pregnancy. This insulin resistance makes it harder for the mother's body to use insulin.

As the fetus continues to grow, the placenta produces more and more insulin-counteracting hormones; the pancreas adjusts to this resistance by releasing additional insulin. The development of gestational diabetes occurs when a woman’s pancreas does not secrete enough insulin and glucose builds up in the blood stream.

Note: Insulin resistance peaks around mid-pregnancy, which is why women are screened for gestational diabetes between 24 and 28 weeks of pregnancy.

Prolactin

Milk production is almost completely controlled by hormones.

Prolactin is produced from the pituitary gland and stimulates enlargement of the mammary glands in preparation for milk production.

Blood levels of prolactin rise during the 8th week of pregnancy and peak at 10 times normal levels, with higher levels of prolactin associated with longer durations of lactation.

Human placental lactogen is made by the placenta, gives nutrition to the fetus, and also stimulates milk glands in the breasts for breastfeeding.

Prostaglandins

Prostaglandins are hormones that effect various aspects of the reproductive system to include the softening (ripening) of the cervix prior to labor and delivery.

Prostaglandins dissolve cervical collagen to encourage the cervix to soften and stretch. If a woman is undergoing induction of labor and her cervix has not softened or ripened, pharmaceutical prostaglandins or mechanical methods that induce the production of prostaglandins can be used to help the cervix efface and dilate (read Prostaglandins and Cervical Ripening).

Labor and Delivery

Near term, estrogen climbs and progesterone drops (described above). At the same time, the pituitary gland boosts its secretion of oxytocin, while the myometrium expresses more receptors for it (further detailed here) – all of which prepare the uterus for the initiation of contractions.

After delivery, high levels of oxytocin contract the uterus to prevent further bleeding, promote placental detachment from the uterine wall, and encourage bonding between mother and baby.

Blood levels of progesterone and estrogen fall after delivery, allowing for the production and release of colostrum. In addition, due to this fall, some women can experience almost an immediate and dramatic reduction of pregnancy-related symptoms caused by these hormones.

Action

Women need to talk with their HCP if they have any concerns regarding their hormone levels during pregnancy. Information regarding HCG levels can be read here.

Women should also read more about various symptoms during pregnancy and what aspects of hormones or other factors can contribute to symptom intensity and duration.

Resources

Hormones during Pregnancy and Labor (U.K. Society for Endocrinology)