Contractions (and Start of Labor)

One of the biggest questions women have at the end of pregnancy is whether or not they are in labor. Although the instant identification of its start still alludes medicine, there is general agreement that true labor can only be recognized through a regular pattern of contractions that continue to grow in strength and intensity, and eventually lead to cervical dilation and effacement.

Some women may recognize this pattern immediately, while it may be gradual for others. Contractions that stop or change in intensity with activity, drinking, eating, or lying down are likely Braxton Hicks contractions (false labor), which can be felt as early as 28 weeks in a first pregnancy.

However, women who have questions regarding whether they may be in labor should call their HCP.

Background

“The greatest impediment to understanding normal labor is recognizing its start”.

Determining the actual start of labor has been described as one of the most important judgments in obstetric care, but there is little agreement on its definition. However:

Labor is most commonly defined by the presence of regular painful contractions and/or some measure of cervical dilation. Dilation and effacement – by themselves – are not the best indicators that labor has begun.

Labor must include contractions of the uterus, the largest muscle in a woman’s body. Further, these contractions must get progressively stronger throughout labor. Researchers do not know exactly how this happens on its own yet, but this progression is the key to determining true labor.

For some women, labor is a concrete event, and they can determine immediately that labor has begun; for others, it is gradual, and cannot be determined until sometime after labor has begun (i.e. 20/20).

Note: The due date is only a guess, and labor can start up to two to three weeks before, and up to 2 weeks afterward.

Although there are clues that labor is near (mucus plug, Braxton Hicks contractions), these events can start hours, days, or weeks from actual labor and delivery.

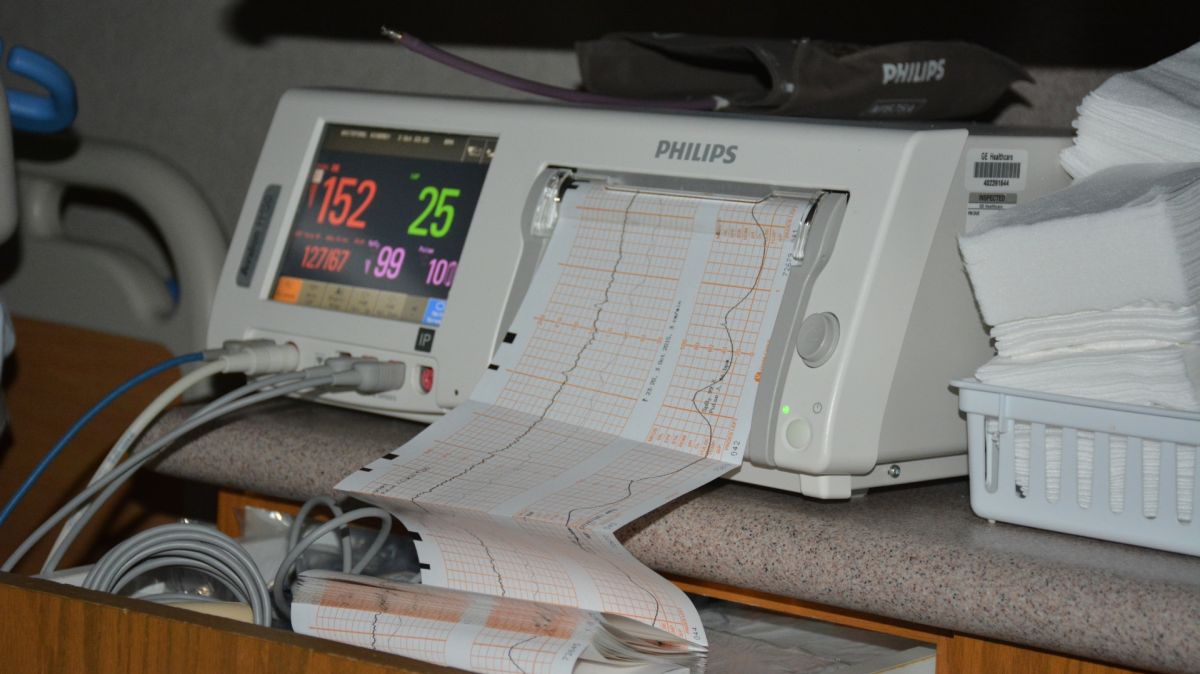

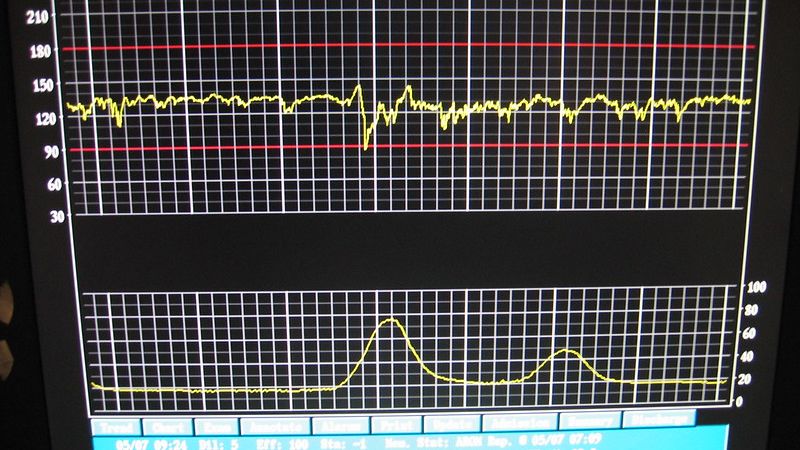

The only way for a pregnant woman to know if contractions are getting stronger and that labor is beginning or progressing, is to either time the contractions and/or receive a vaginal exam to determine if contractions have been strong enough to promote cervical change.

False Labor (Braxton Hicks)

As pregnancy enters its seventh month, progesterone levels plateau and drop, while estrogen levels increase.

The increasing ratio of estrogen to progesterone makes the uterine muscle more sensitive to stimuli that promote contractions. Earlier in pregnancy, the rise in progesterone prevents contractions, which is no longer necessary toward the end, so progesterone drops. The initial change in hormone ratio can result in false (or prodromal) contractions called Braxton Hicks (BH) contractions.

Further, these contractions are beneficial and easily triggered late in pregnancy. Known triggers include physical activity, a full bladder, sex, and dehydration. These triggers cause potential “stress” to the fetus, which requires additional blood flow to the placenta. To get this additional blood flow, the uterus must tighten and contract in order to get oxygen-rich blood to the fetus.

Note: These triggers should not be done purposefully to initiate labor. Although BH contractions can be easily triggered, they do not appear to trigger true labor. Further, BH contractions do not cause dilation of the cervix, although they may help soften it.

Braxton Hicks contractions are present in all pregnancies but are felt and experienced differently among pregnant women.

Sometimes women can barely sense these contractions, feeling only a painless tightening. At other times, the contractions can be strong or painful.

These contractions tend to come and go, get worse as the day goes on, and are more common when women are fatigued. They are also irregular, don’t get stronger or closer together as time passes, and stop with position or movement changes, or they simply stop on their own.

To help determine if contractions are false, the key is to ask: how often, how long, how strong, where are they felt, and do they stop with movement or rest.

If a woman was resting, she should get up and walk.

If a woman was engaging in physical activity, she should rest.

Distraction can also help, such as a warm bath, music, napping, reading, or some other calming activity.

Since dehydration is often a cause, it is recommended women increase fluid intake if they feel these contractions often. (Dehydration increases secretion of the hormone vasopressin, which likely cross reacts with oxytocin receptors.)

If these activities do not appear to stop or chance these contractions, and they begin to get stronger and closer together, the woman is likely experiencing true labor.

Physiological Start of Labor

The initiation of true labor contractions is complex, and most likely occurs due to signals from both the mother and fetus.

Uterine stretch is hypothesized to be a possible "starter" since multiple births generally are at higher risk of preterm birth, as well as those with too much amniotic fluid. Finally, stretching of the myometrium and cervix by a full-term fetus in the head-down position is also regarded as a stimulant to uterine contractions.

The fetus reorients facing forward and down with the back top of the head engaging the cervix which helps it efface and dilate. This engagement of the cervix sends nerve impulses to the hypothalamus, which releases oxytocin from the pituitary gland that bind to the growing number of receptors in the uterus (the fetus and placenta also release oxytocin).

The placenta releases prostaglandins into the uterus at the same time, increasing the contractions. A positive feedback relay occurs between the uterus, hypothalamus, and the pituitary to assure this cycle continues. As more smooth muscle cells are activated in the uterus, the contractions increase in force and intensity.

Oxytocin and prostaglandins have primary roles in the start and/or continuation of labor. The pharmaceutical versions of these compounds are very successful in the induction and augmentation of labor when administered to a woman with either an unripe cervix (prostaglandins), or in labor that has slowed or stalled (oxytocin).

The fetus may also contribute to the start of labor through as-of-yet-unidentified bloodborne agents that act on the placenta, or are secreted into the amniotic fluid.

One of these agents may be surfactant. Surfactant, which reduces surface tension within the lung after birth, is essential for breathing air. Since this happens near the very end of term, it is possible that surfactant is secreted by the fetal lungs into amniotic fluid and serves as a hormonal signal for the start of labor.

Since most preterm babies have not yet produced surfactant (or enough of it) by the time they are delivered, it is also clear that other processes are involved in labor in general, and that preterm labor is likely started due to separate mechanisms unique from full-term labor (such as infection).

True Early Labor (1 to 3 or 4 cm)

When contractions noticeably begin taking on a pattern, this is known as the first stage of labor.

True labor can be distinguished from false labor through frequency and strength of contractions. True labor contractions continue to increase and eventually will not stop with movement or position changes (which is opposite from BH). They are also regularly spaced apart, get closer together as time progresses, and pain/discomfort may start from the back and move to the lower abdomen.

Early contractions are relatively painless at first, but gradually build in intensity, starting the top of the uterus and radiating through the abdomen and lower back, in which the abdomen becomes hard to the touch. This tightening does the reverse for the cervix and lower portion of the uterus, which relaxes and stretches.

Once early labor begins (generally 1 to 3 or 4 centimeters), it is routinely advised that women rest at home until contractions are about 5 to 10 minutes apart. Although most sources indicate women can tell when to go to the hospital by how much more painful contractions are getting, it is also possible to tolerate or expect a higher level of pain, and therefore remain home for longer than planned. Timing contractions at their on set can help women avoid this scenario.

In general, however, women should call their HCP or go immediately to a hospital or birthing center if:

Contractions are between 5 and 10 minutes apart for about an hour, are too painful to walk or talk through

Membranes rupture ("water breaks")

Vaginal bleeding is present

Fetal movements dramatically change or stop

The woman is very uncomfortable or unsure if labor has begun

Women with uncomplicated pregnancies, intact membranes, and cervical dilation less than 4 cm may either get sent home or be monitored for a certain period of time on the labor floor. Women determined to be in labor with cervical change and persistent contractions are generally admitted.

When there is a clear change in how frequent, how strong, and how long contractions are, and the woman is clearly uncomfortable and cannot walk or talk, she is likely moving into active labor.

Contractions during Active Labor

It was previously thought active labor should begin at 4 cm dilation, but other sources indicate that based on variable dilation and contraction rates, some women may not begin active labor until around 6 cm (read Dilation and Effacement for dilation rates).

During active labor, contractions get stronger, longer and more painful. There is less time to relax in between, pressure can be felt in the back and rectum, dilation is much faster than in early labor, and the fetus starts to move into the birth canal as full dilation gets closer.

As the cervix continues to get closer to 10 cm, the timing between contractions decreases. When the cervix is only at about 1 to 2 cm dilated, contractions may occur once every 30 minutes. As the cervix gets wider, they might occur once every 10 to 20 minutes, and then once every few minutes. Note: Some women may not experience contractions until as far along as 4 cm.

The most difficult phase of this still first stage of labor is “transition”, which is estimated to occur between 7 and 10 cm. Contractions are very powerful, with the least time in between, and the cervix stretches the last few centimeters. Many women feel shaky, irritated, sweaty, hot, cold, or nauseated. Contractions last about 60 to 90 seconds and come every 2 to 3 minutes.

Contraction Pain

Labor pain is highly individualized and depends on numerous factors, to include a woman’s threshold for pain, her ability to prepare and cope, her support system, and her understanding of what is happening at any stage.

Not only do contractions feel different for each woman, they may also feel different from one pregnancy to the next in the same woman.

Physiologically, the pain of labor is attributed to a lack of oxygen in the uterine muscle during contractions, which is completely different than any other muscle contraction. This is in addition to compression of the blood vessels and groups of nerves in the cervix and lower uterus, as well as cervical stretching.

Additionally, feelings of pain, stress, and anxiety trigger a release of stress hormones such as cortisol and endorphins, which can adversely affect uterine activity, thereby increasing perception of pain (read Fear of Childbirth).

Early contractions are often described as a cramping or tightening sensation that starts in the back and moves around to the front in a wave-like manner, pressure in the back, a “knotting up”, dull aches in the back and abdomen, or strong menstrual cramps.

These contractions will gradually increase in intensity until the contraction peaks, then slowly subsides and goes away. As the strength of each contraction increases, the peaks will come sooner and last longer, and pain can radiate to the sides, hips, and thighs.

Once dilation is complete at 10 cm, the woman can either immediately begin to push with continuing contractions, or rest and wait, in what is known as delayed pushing.

Pushing

The urge to push is normally greatest between 7 and 10 cm. Women are often told to avoid pushing prior to full dilation. Although there are very few studies regarding cervical trauma or complications to the baby if this occurs, the main complication is the woman’s exhaustion level, as the baby cannot pass through a cervix that is not fully dilated.

The length of time it can take from the first push to delivery is affected by numerous variables. Some women may only need a couple pushes, while other women may need 2 to 3 hours.

Evidence-based research regarding the best pushing positions are inconsistent and often controversial; it is therefore recommended that women should be encouraged to choose positions that make them the most comfortable (read Pushing).

Action

Women are advised to call their HCP or seek emergency care if they believe they are experiencing preterm labor, which can include contractions, bleeding, or both.

In general, women should call their HCP or go immediately to a hospital or birthing center if contractions are between 5 and 10 minutes apart for about an hour, are too painful to walk or talk through, membranes rupture, (water breaks), vaginal bleeding is present, fetal movements dramatically change or stop, or a woman is very uncomfortable or unsure if labor has begun.

HCPs, including midwives, doulas, and registered nurses are a crucial part of the process for helping women through contraction pain. Their advice is important and is based on years (and decades) of observing and helping women through childbirth.

Although women in labor are the ultimate decision makers on what methods they want to use and should be encouraged to do what works for them, HCPs are there to enhance, encourage, and remind them of certain techniques that can help relieve pain.

Women should be aware of their different options for moving around, dealing with pain, medications, various positions, and pushing strategies to give them as many choices as possible when contractions occur.

Some women cannot tell what methods are likely to work best until contractions begin, and having exposure to different techniques provides more options and better pain control.

Women may alternate between wanting to be touched and wanting to be left alone; women can also grunt or moan when contractions reach their peak.

Numerous medications are available to further assist with pain relief; one of the most common options is an epidural.

Slow, easy breathing works well for some women, while others find an uneven breathing pattern more helpful.

Birthing balls, walking around, and showering are some of the most often attempted pain-relieving methods for dealing with contractions.

Ice packs, heat, massage, and cold washcloths are also options for contending with pain.

Relaxing, resting, and potentially changing positions between contractions may help women keep their energy as well as their physical and mental strength.

Sucking on ice chips can help keep a woman’s mouth from getting too dry, especially in between various breathing techniques.

Some women may also prefer to eat when possible during various stages of labor.

Emptying the bladder frequently can also assist with discomfort. Women should be encouraged to walk to the bathroom while they can. During labor, some women may not be able to tell if they need to empty their bladder; HCPs can help (bed pan, catheter, walking assistance).

Resources

How to Tell When Labor Begins (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists)

Preterm Labor and Birth (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists)

Braxton Hicks Contractions (StatPearls/NCBI)