Uterus

The uterus changes in size, weight, volume, and blood flow in order to support, develop, and protect a pregnancy. Researchers are still learning about how the uterus performs these functions, to include its response to labor hormones and contractions.

The largest affect the uterus has on a pregnant woman is its obvious stretching – which causes discomfort in moving, sitting, sleeping, standing, and even breathing.

The uterus has the capability to stretch to a capacity of up to 1,000 times more than its pre-pregnancy state. Fortunately, none of these discomforts are harmful or permanent, and women get a slight break around 36 weeks of pregnancy, or as soon as the baby drops into the pelvic cavity.

The changes of the uterus, mostly its surrounding muscles and ligaments can, however, affect a woman long after delivery. Knowledge of these changes can help women prepare for (and even prevent) potential short- and long-term complications both during and after pregnancy.

Background

Knowledge of the function and biomechanics of the uterus during pregnancy is still only known at a basic level, mostly due to a lack of safe and effective imaging and other techniques during pregnancy.

Understanding the uterus during pregnancy goes far beyond how it enlarges and returns to normal. Figuring out the initiation, strength, stability, and length of contractions, how this process occurs, what inhibits it, what starts it too early, and how to heal quickly after delivery to prevent hemorrhage – are all aspects of uterine function that require further research.

Implantation poses significantly more trouble to researchers than labor and delivery, and theories about how the body assists, reacts, and even rejects embryos – and the uterus’ role in this process – is even more unclear.

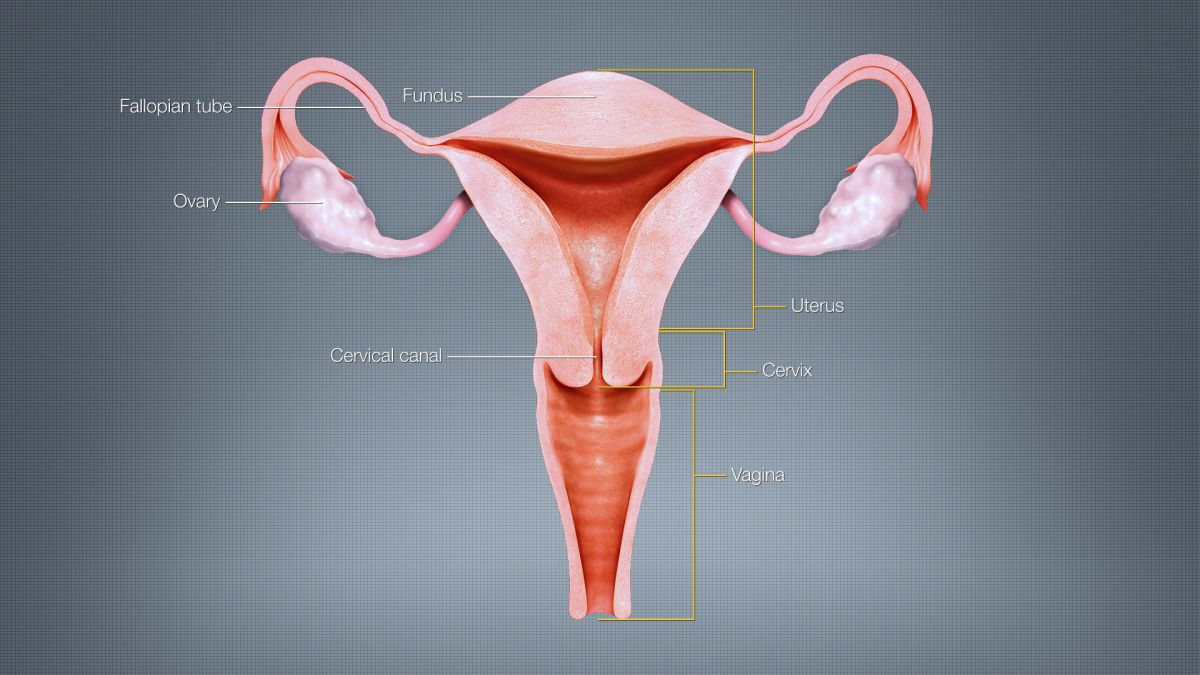

Anatomy

The uterus is a muscular, thick-walled organ, approximately the shape and size of a pear, and sits in a forward position within the pelvic cavity. The uterus averages 7 to 8 cm in length, 5 to 7 cm in width, and about 2 to 3 cm in wall thickness. The uterus may measure 9 to 10 cm in length in women who have had more than one pregnancy.

The uterus weighs approximately 2.5 ounces (70 grams) and is almost solid, except for a cavity of 10 milliliters (ml) or less.

The cervix is located at the bottom of the uterus, is cylindrical in shape, and dilates and effaces during labor and delivery.

The Fallopian tubes are located on either side of the top of the uterus and measure 10 cm long and about 1 cm in diameter. After ovulation, the egg is fertilized by a sperm inside the Fallopian tube. The fertilized egg than travels through the rest of the Fallopian tube to the uterus.

The uterus is attached to the inside of the pelvis by two round ligaments, one on each side. These ligaments are about 10 to 12 cm long and help support the uterus, keep it in place, and support the weight of a pregnancy. As the uterus stretches and expands, tension on these ligaments can cause Round Ligament Pain.

Blood Flow

During pregnancy, the blood vessels in the uterus enlarge and its lining thickens. This lining provides nutrients to the embryo after implantation. If implantation does not occur, this lining sloughs off during menstruation (i.e. period starts).

For implantation and placental development to successfully occur, the entire uterine circulation is transformed to support it and blood flow increases dramatically, ranging from a 3.5-fold increase to a 40-fold increase compared to pre-pregnancy. (Note: This large range is due to different methods of blood flow measurement.)

Total blood flow of the uterine artery increases from a baseline of 20 to 50 ml/min to 450 to 800 ml/min in women pregnant with one baby, and up to 1,000 ml in women with twins.

The diameter of the uterine artery almost doubles in size, and the velocity of blood in the artery in week 36 of pregnancy is nearly eight times faster than prior to pregnancy.

The uterus can also affect blood flow to the the lower half of the body. As the uterus gets larger, it can block blood flow returning from the legs to the heart; this delay causes swelling in the legs, ankles, and feet.

Women are also advised to avoid lying flat on their backs beginning in the second trimester to avoid a more significant blockage of blood that can lead to feelings of dizziness or faintness (read more).

Stretching

Women have wide variations in uterine size at the same week of pregnancy for a variety of reasons such as: body shape, height, fibroids, carrying multiples, amniotic fluid abnormalities, and size of the fetus.

As pregnancy progresses, the uterus expands through the stretching of current muscle fibers as well as the development of new ones.

The baseline cavity of the non-pregnant uterus is about 10 ml in volume. This volume increases to 1,000 ml at 20 weeks and to 4,500 ml (4.5 liters) at 40 weeks (volume has been documented to be as high as 20 liters); a capacity that is 500 to 1,000 times greater than prior to pregnancy.

By term, the uterus weighs nearly 39 ounces (1,100 grams) without the fetus or fluids (compared to 2.5 ounces before).

The walls of the uterus gradually thin as stretching continues to occur. By term, the myometrium is only 10 to 20 mm thick (1 to 2 cm), and the fetus can easily be felt through the abdomen.

Fundal Height

The uterus is somewhat circular by 12 weeks of pregnancy and feels like a grapefruit; after this point, the uterus will grows faster in length than width and becomes more oval.

Between 12 and 14 weeks of pregnancy, the uterus transforms “from a pelvic to an abdominal organ” as it lifts out of the pelvic area. Further, a retroverted, or “tilted” uterus should correct itself during this same time frame.

The top of the uterus reaches the belly button around 20 weeks, contacts the abdominal wall, and starts to shift the intestines up and to the side. The uterus eventually reaches almost to the liver.

Fundal height measurement, the distance from the top of the uterus (fundus) to the pubic bone, can be used to define gestational age and is routinely done at every prenatal appointment after 12 weeks, but is most useful after 20 weeks.

This method of measurement has a wide range of accuracy but is still a very good resource tool when ultrasound is not available. It is generally assessed that each 1 cm increment in fundal height corresponds to one week of gestation (32 cm fundal height = 32 weeks of pregnancy).

However, a difference of 2 to 3 cm in either direction is considered normal. Therefore, a woman at 32 weeks of pregnancy can have a fundal height between 29 and 35 cm (and still be within normal range).

Note: At 36 weeks, the fundal height is about 2 inches below the xiphoid process (sternum), but at 40 weeks, it’s 4 inches below. This is due to engagement and descent of the baby’s head, which lowers fundal height. This is the “drop” that most women report, and also results in easier breathing.

Pelvic Floor

The uterus (plus the fetus and amniotic fluid) gets heavier as pregnancy progresses, and the increasing pressure/weight on pelvic floor muscles weakens them and can lead to various urinary tract symptoms during and after pregnancy.

Women who have had more than one pregnancy experience a more cumulative loss of pelvic floor muscle strength, as these muscles do not always completely heal between pregnancies.

Labor and Delivery

Progesterone has a dominant role throughout pregnancy in controlling the uterus. Progesterone inhibits uterine contractions from the very onset of pregnancy.

Near the end of pregnancy, the placenta boosts estrogen production to overpower the effects of progesterone which makes the uterus more sensitive to the initiation of contractions. A continued drop of progesterone allows contractions to intensify and progress to true labor.

The change in the ratio of estrogen and progesterone can be felt by some women as Braxton Hicks contractions. Some women can feel these “false” contractions even before this ratio changes, indicating other factors besides these two hormones contribute to these contractions.

For these hormones to have an effect on the uterus, the uterus must have receptors for them. As pregnancy progresses, the number of oxytocin receptors in the uterus increases (by 100-fold at 32 weeks and nearly 300-fold at the onset of labor). Oxytocin is then released by the pituitary gland at labor, docks to its uterine receptors, and helps initiate and progress contractions.

Some women may not experience this surge in receptors, and others may even lose receptors during labor, especially during lengthy inductions. This can cause a failure to either start labor, progress, and/or respond to administered oxytocin (read Induction).

The placenta releases prostaglandins into the uterus at the same time, increasing contractions. A positive feedback relay occurs between the uterus, hypothalamus, and the pituitary to assure this cycle continues. As more smooth muscle cells are activated in the uterus, the contractions increase in force and intensity.

Postpartum

Immediately after delivery, the top of the uterus is contracted to slightly below the belly button. After the first two days postpartum, the uterus begins to shrink further. Within two weeks, the uterus has descended into the cavity of the pelvis, and back to approximate pre-pregnancy size by 6 weeks postpartum.

In women who have had multiple pregnancies, the uterus may remain slightly larger than prior to those pregnancies.

Painful cramps of the uterus after delivery is relatively common and may feel like strong menstrual cramps rather than labor contractions. They begin to ease around 72 hours postpartum.

Breastfeeding can also initiate these cramps and serve a purpose by further contracting the uterus to assist in the prevention of hemorrhage.

Action

Any concerns or questions women have regarding their uterine size or position (i.e. "tilted") should ask their HCP for clarification or more detail.

Women should never be afraid to continue asking questions so they can better understand their anatomy, their overall health, and the health and progress of their pregnancy.

As the uterus enlarges and grows out of the pelvic cavity, it can start to add pressure to the back muscles, spine, hips, and pelvis. Women who experience pain, especially those who experience it early or are carrying multiples, should ask their HCP about support belts and garments.

It is important to prevent chronic back pain as much as possible by managing it early (read Back and Spine).

For women concerned that their fundal height measurement does not line up with their gestational age, they should remember its wide range of accuracy. They should also bring their concerns to the attention of their HCP who will likely relieve a her anxiety, or potentially recommend ultrasound for better evaluation.

Partner/Support

The best way for partners to support a woman's growing uterus is to help her manage its associated symptoms. The enlarged uterus can wreak havoc on a woman's back, pelvis, hips, and joints of the ankles and feet. Women can also experience shortness of breath as the uterus crowds the ribs and shifts up the diaphragm. At term, the uterus is so large it can block blood flow return to the heart, causing swelling.

Partners and those who support pregnant woman should read the following pages to better understand these symptoms in more detail:

Back Pain (Back and Spine)

Joint Pain (Musculoskeletal System)

Resources

Video of uterus "contracting" for menstrual cramps (GRAPHIC): Provides a lesson in uterine anatomy prior to pregnancy; similar to what may occur during contractions. NOTE: This video may be graphic for some women; it uses a cadaver/organ (TikTok: Institute of Human Anatomy)

Uterine Anatomy (Teach Me Anatomy)

Below: 3D Video of Uterine Anatomy: