Respiratory Tract

Although lung development and growth begins early in pregnancy, the structural changes required for breathing do not occur until the final few weeks of pregnancy. Babies who are born prior to 36 weeks face the biggest threat of immature lungs.

However, survival at these early stages is improving, and babies born as early as 26 weeks have a good prognosis with intensive care.

The lungs are filled with fluid for the entirety of pregnancy until after delivery, when this fluid is replaced by air with the baby's first breath.

Note: Hiccups may be related to lung development. Frequently felt by pregnant women, fetal hiccups could serve as a function of the fetal diaphragm to move amniotic fluid in and out of the both the lungs and gastrointestinal tract – which is necessary for their proper development.

Background

Lung growth and development starts early in pregnancy and continues until term. The entire airway, like the skin, is constantly exposed to external elements. The lungs must develop and mature enough to perform gas exchange required for breathing; they must also cope with the environment outside the uterus, such as air temperature variation and potential allergens.

However, despite significant research, the understanding of fetal lung development is still at a basic level, especially in relation to preterm birth.

The upper respiratory tract includes the nose, nasal cavity and the pharynx. The lower respiratory tract includes the larynx, trachea, bronchi, lungs, and diaphragm.

There are five main stages of lung development in fetuses, but there is no total agreement about when or how long these stages occur across different pregnancies. The five steps always occur in order, but fetuses can differ on when each stage begins and how long it lasts (five stages: embryonic, pseudoglandular, canalicular, saccular, and alveolar).

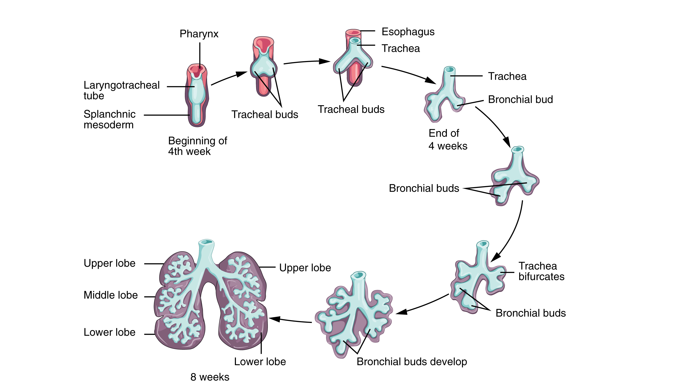

Development

The respiratory tract, diaphragm, and lungs start forming early in pregnancy, and develop from the foregut. At approximately 6 weeks of pregnancy, the right and left lungs appear as two outpouchings of the foregut wall.

Each bud then starts a repetitive process of branching. Three lobar buds develop in the right lung bud and two lobar buds develop in the left (the right lung is slightly larger than the left one which is the same for adults).

These buds continue to divide up to 15 to 20 times.

By 15 weeks of pregnancy, hair-like cilia appear, whose job it is to move debris and other contaminants out of the airway.

By 18 weeks, all major elements of the lung have formed, except those involved with gas exchange, as breathing outside the uterus at 18 weeks is not possible. However, cells that will become the tiny air sacs (alveoli) have started to appear.

It is estimated that a newborn has between 20 and 70 million alveoli at birth, with about 300 million by adulthood. Development of these sacs starts around 20 weeks but newborns cannot breathe without assistance until about 32 weeks (see Preterm Lung Development, below).

Near term and at birth, the fluid that fills the alveoli is absorbed (and replaced with air), the defenses that protect the lungs against the harmful environment are activated, and the surface area for gas exchange increases dramatically.

Fetal Breathing and Hiccups

Around 10 to 12 weeks of pregnancy, fetal "breathing" movements start. These movements cause additional stretching of the lung tissue and move amniotic fluid in and out of the lungs.

Fetal lung liquid plays a crucial role in the growth and development of the lungs by maintaining them in a distended state which stimulates their growth.

This liquid is produced by the lungs and leaves via the trachea and is either then swallowed or escapes into the amniotic sac, entering the amniotic fluid.

The daily rate of lung fluid into the amniotic fluid is estimated to be around 300 to 400 milliliters (ml), and less than 5 ml per breath. At term, the fetus may “breathe in” approximately 600 to 800 ml/day at a rate of 20 to 30 minutes each hour.

Oligohydramnios (too little amniotic fluid) slows lung growth, possibly by lung compression or by affecting fetal breathing movements or the volume of fluid within the potential airways and airspaces.

In 1899, it was suggested that hiccups were a form of preparation for the fetus to strengthen the muscles involved in breathing. Fetal hiccups are often described by pregnant women as jerky movements that “come and go”.

Studies with real-time ultrasound have confirmed the fetus experiences hiccups; they have been observed as early as 9 weeks of pregnancy (but may not be felt by the mother until much later). These hiccups are not harmful and are often a reassuring sign of healthy development.

One study made 35 two-hour recordings of fetal heart rate and movements and noted 14 periods of hiccups, with an average duration of 3.5 min (range was 1 to 8 minutes). The amount of hiccups during those time frames varied from 10 to 21 per minute.

A meta-analysis published in November 2021 found that fetal hiccups and regular episodes of vigorous movement (after 28 weeks of pregnancy) were associated with decreased odds of late stillbirth.

Although the fetal diaphragm appears to be the main muscle involved, not much is known about the diaphragm's development. However, the onset of both hiccups and breathing have been described roughly one to two weeks after its development, therefore an association is likely.

There are several theories as to why the fetus may experience hiccups (there is no known purpose for hiccups in adults). Hiccups during the first half of pregnancy may help force amniotic fluid into the early forming gut, which would potentially assist the development of the gastrointestinal tract.

Other suggestions have included clearance of meconium the fetus has breathed in, or that hiccups are training for suckling, but these are much less likely. Hiccups would move meconium further in, and the muscles involved in suckling are not involved in hiccupping.

Some researchers have noted that hiccups may help modulate heart rate during the last trimester, while others say hiccups have no effect on fetal heart rate.

Regardless, fetal hiccups are the main type of diaphragmatic movement until 26 weeks of pregnancy, after which fetal breathing becomes the main movement. Researchers disagree on whether hiccups increase or decrease in frequency until term.

Surfactant System

From about 26 weeks of pregnancy to term, gas exchange capability continues to improve as air sacs develop. These sacs are eventually coated by surfactant, a mixture of fats and proteins that prevents air sacs from collapsing after every breath. The surfactant system is considered mature at approximately 36 weeks, with increasing production in the last two weeks of pregnancy.

Aeration of the lungs occurs at birth when the lung fluid in the sacs is replaced with air.

Without surfactant, the alveoli would collapse, requiring a tremendous amount of effort for every single breath.

Breathing is possible at 28 weeks because some thin-walled sacs have developed, but the system is still very immature and intensive care would be required.

Preterm Lung Development

Dramatic and significant structural changes to the lungs occur in the last two months of pregnancy, and this is the system most critically immature in infants born prematurely.

Surfactant deficiency is the major cause of Respiratory Distress Syndrome (RDS), affecting up to 2% of all newborns. However, in babies born at 26 weeks of pregnancy or greater, prognosis for survival is very good with proper care.

Several treatment techniques are used to treat RDS: steroids to promote lung maturity, various forms of positive pressure to maintain the lungs in an open state, and the administration of (medical) surfactant.

There are also potential complications of the treatment of fetuses and preterm infants with repeated and/or high doses of corticosteroids, which can help fetal lungs mature more quickly.

Therefore, there is a difficult risk vs. benefit balance of using steroids in preterm infants, and research is ongoing regarding the best choice of glucocorticoid, optimal dosing, number of doses, and potential toxicities.

Babies may also be mechanically ventilated. However, this tends to cause damage as the lungs are getting oxygen in a way they are not mature enough to receive in that manner. This is usually done to save their lives.

Action

Women who are concerned about their babies' lung development, movements, or have questions regarding fetal hiccups, should talk to their HCP.

Women should have routine appointments and ultrasounds with their HCP for regular monitoring and to learn the signs of potential preterm labor. It may be helpful for women understand the difference between real contractions and false labor, as both can occur prior to 28 weeks.

Women can read more detailed information on fetal movement here.

Resources

Development of the Lung (Cell and Tissue Research/NCBI)

Respiratory System Development (UNSW Australia/Embryology; Dr. Mark Hill)

How Children's Lungs Grow (British Lung Foundation)