Vaccines

Vaccinations during pregnancy can protect a baby even before birth through the passive transfer of the mother’s antibodies through the placenta. This is critical, as vaccinations for influenza and pertussis – both of which can be severe for an infant – do not begin until at least six months of age.

While there are many recommended vaccines for children and adults, only two are frequently and routinely recommended during pregnancy – seasonal influenza and Tdap (tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis/whooping cough).

There are several other vaccines that may be recommended by an HCP to a pregnant woman if the woman is considered high risk for certain vaccine-preventable infections.

Research to date, which has been vetted by the U.S. National Academy of Medicine, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, World Health Organization, American Academy of Pediatrics, and numerous other agencies has demonstrated the safety of the influenza and Tdap vaccinations during pregnancy.

Pregnant women who have any questions or concerns regarding vaccinations during pregnancy should speak with their HCP.

Background

Medicine has started to move from treatment to prevention, and obstetrics is no exception. Women can take certain actions during pregnancy to protect their baby from potentially serious illness in the first few weeks and months of life.

Vaccinations during pregnancy have this goal, and vaccinations designed to be administered during pregnancy specifically to protect the infant (rather than the mother) are in development (i.e. RSV).

Newborn infants are at high-risk for significant illness and even death from certain infectious diseases because their immune systems are not fully developed. Further, newborn infants cannot receive vaccinations until at least six months of age or older for most vaccines, leaving them critically vulnerable – especially if born during the fall/winter months.

Vaccinating the mother during pregnancy is a perfect mechanism to not only protect the mother (i.e. influenza), but to provide a baby with antibodies prior to birth. When the mother is vaccinated, her antibodies safely transfer through the placenta.

Antibodies from vaccinations during pregnancy are estimated to provide protection to an infant until at least six months old, the time in which the first (post-delivery) vaccinations begin.

Currently, no vaccine is officially approved for use during pregnancy specifically to protect the infant (Read Research and Pregnant Women); this does not mean that certain vaccines are unsafe.

Women are often excluded from clinical trials which are required to “officially” obtain approvals – however, safety data has accumulated for decades.

It was not until 2015 in which the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) convened the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee to discuss clinical trial considerations for vaccines for use during pregnancy (the Committee discusses vaccines for all populations).

Note: According to meeting notes posted to the FDA website, the last vaccine discussed specifically for pregnancy was Group B Strep in May 2018 (as of September 2020).

Research to date has unequivocally demonstrated there is no association between vaccines and autism. Additionally, studies have further supported the safety and effectiveness of vaccines in reducing infectious disease.

General Safety

All vaccines are tested for safety under the supervision of the FDA. The vaccines are checked for purity, potency, and safety, and the FDA and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) monitor the safety of each vaccine while in use.

Some people might be allergic to an ingredient in a vaccine (such as egg), and should not receive the vaccine until they have spoken with their HCP (see how vaccines grow in eggs, under Resources). Further, since some vaccines are available at local pharmacies, pregnant women should always call their HCP prior to getting any vaccine.

Side effects of vaccines (mostly injection-related) include:

Soreness and redness at injection site

Fatigue

Muscle ache

Fever

Headache

Rash or red bumps

Joint pain

Severe allergic reaction in very rare cases

Swelling of neck glands and cheeks

Any pregnant women who experiences any side effect from a vaccine should call their HCP immediately or seek emergency care if severe.

Types

Vaccines are classified as live attenuated; inactivated or killed; toxoid; or subunit or conjugate vaccines.

Live attenuated vaccines may contain living organisms that have been weakened or altered so as not to cause infection. These vaccines do not cause the development of a full infection, but enough to stimulate a strong immune response so the body mounts a response nearly equivalent to what would follow natural exposure or infection.

Vaccines that contain live viruses are not recommended for pregnant women and are routinely avoided; however, to date, any potential harm from these vaccinations during pregnancy is still only theoretical.

Live vaccines are considered strong, and in some cases, can induce unwanted effects compared to other types of vaccines. For example, a live attenuated vaccine against rotavirus can cause severe intestinal inflammation.

Live attenuated vaccines include: Measles, Mumps, and Rubella (MMR); Rotavirus; Smallpox; Chickenpox; Yellow Fever

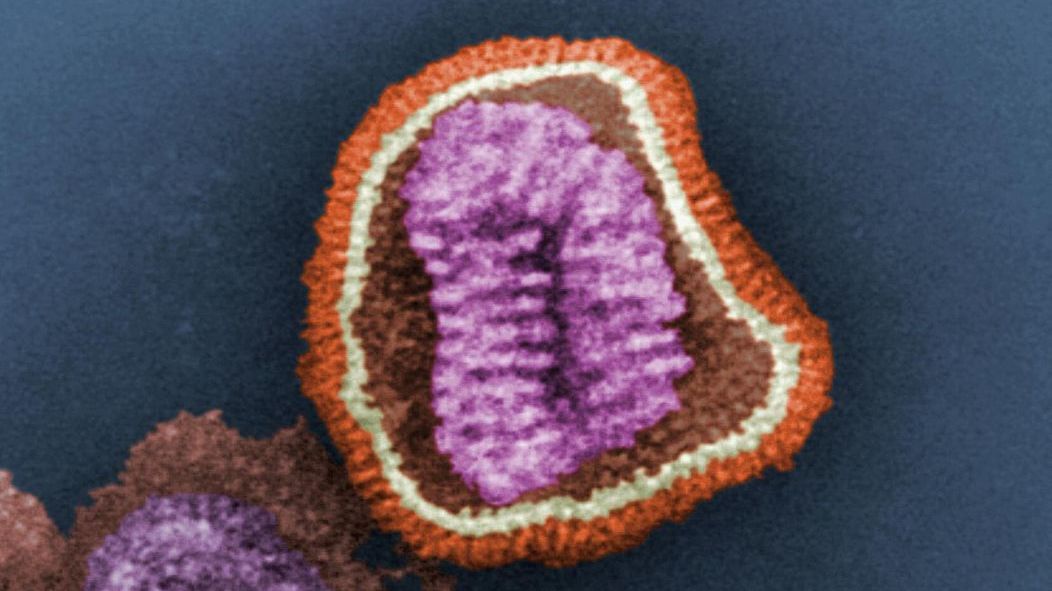

“Killed” or inactivated vaccines contain a “dead” virus; these vaccines are often administered during pregnancy. Inactivated vaccines do not create as strong as an immune response as live attenuated vaccines; therefore, they need to be given seasonally or in boosters.

Inactivated or killed vaccines are created by inactivating a pathogen using heat or chemicals. Inactivating processes destroy the pathogen’s ability to replicate; therefore it does not contain any living or infectious particles and thus cannot result in clinical infection (i.e. the inactivated influenza vaccine cannot give someone influenza).

Inactivated vaccines: Influenza; Hepatitis A; Polio; Rabies

Subunit, recombinant, polysaccharide, and conjugate vaccines use only a specific part of the germ/virus, such as its protein, sugar, or casing; this causes a strong immune response, but only to a targeted aspect of the disease. These vaccines are considered very safe and effective – to include those with weakened immune systems and chronic conditions.

Subunit, recombinant, polysaccharide, and conjugate vaccines: Hepatitis B; Human Papillomavirus (HPV); Whooping Cough (part of Tdap and DTap); Pneumococcal Disease; Meningococcal Disease; Shingles (boosters of these vaccines are often required).

Toxoid vaccines use only the toxin produced by a germ that causes a disease, which – when exposed – creates an immune response to the toxin, not the germ; these vaccinations also require boosters as antibodies fade.

Toxoid vaccines: Diphtheria; Tetanus (see Tdap, below).

Vaccine Recommendations

There are certain vaccines recommended during pregnancy, to include each pregnancy, even when pregnancies occur close together in the same woman (although others may not be necessary).

Of all vaccines commonly recommended by the CDC and FDA for adults, two are directly recommended for administration during pregnancy, four are recommended based on a pregnant woman’s risk factors, and two are specifically recommended during the postpartum period.

Recommended during: Tdap, Influenza

Based on risk factors: Hepatitis A, Hepatitis B, Meningococcal, and Yellow Fever

Postpartum: MMR and Tdap (if boosters are required; influenza may also be recommended depending on season)

Not recommended during: Live attenuated influenza (nasal vaccine), Varicella (Chickenpox), MMR, HPV

*No specific recommendations have been given for the Pneumococcal vaccine

The seasonal influenza vaccine is also recommended during pregnancy by obstetric organizations in Canada, the United Kingdom and other European countries, mainly to protect pregnant women who are at increased risk of severe infection, as was demonstrated during the 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1).

Influenza

Influenza is a contagious, sometimes severe viral disease that can affect both the upper and lower respiratory tracts in newborns, children, adults, the elderly, and pregnant women. Common symptoms include runny nose, high fever, body aches, cough, and sore throat (read Influenza).

Influenza (flu) vaccination of pregnant women is considered the best option to reduce flu infection and its related complications – which can be severe – in pregnant women and infants under six months of age.

Pregnancy is considered a risk factor for developing severe influenza infection, reported by different countries all over the world. Pregnancy may possibly be a stronger risk factor than obesity, diabetes, and cardiac failure.

Influenza in infants under six months old can be devastating; this age group is at risk for higher hospitalization rates than children six to twelve months of age during flu seasons.

The seasonal flu vaccine (inactivated) is typically advised during November through March but is available as early as the end of August in some parts of the United States (U.S.). Note: The influenza nasal spray vaccine is made from a live virus and is not recommended during pregnancy.

During 2000 to 2010, the administration of the flu vaccine to pregnant women was relatively low, estimated at less than 20%, likely due to concerns over safety.

More than 40 years of research, safety data, and hundreds of thousands of vaccinations have demonstrated the safety and effectiveness of the influenza vaccine during pregnancy – for both pregnant women and their newborns.

Specifically, there is a strong lack of association between autism, malignancy, birth defects, or fetal death. Additionally, some studies found better pregnancy outcomes in those who were vaccinated when compared to women who were not vaccinated.

Further, during the 2009–2010 influenza A (H1N1) vaccination program, clinical trials were conducted and several monitoring systems were established; these evaluations did not identify any safety concerns in vaccinated pregnant women or their infants.

Based on this reassurance regarding safety, researchers have advocated for future targeting of specific safety-related data regarding the first trimester of pregnancy, which is more limited than the second and third trimesters.

Influenza vaccinations during pregnancy are also very effective for both mother and baby. Together with safety data, this has led professional health and obstetric organizations to recommend the season flu vaccine to all pregnant women.

Data have shown the vaccine prevents neonatal morbidity and hospitalization from influenza virus infection in the first six months of life. Numerous studies have also found neonatal antibodies at approximately the same level as levels in the mother’s blood.

Although there is overall less data during the first trimester, it appears the stage of gestation does not seem to influence the response rate; effectiveness in the first trimester is similar to second and third trimester vaccination.

Further, while a review of articles between 1964 and 2013 indicated the vaccine may only provide moderate protection in some cases, the same study pointed out that even if influenza vaccination provides sub-optimal protection in pregnant women, its potential to provide protection to young infants is enough justification to recommend the vaccine.

Several countries including the U.S., Canada, and the United Kingdom recommend seasonal influenza vaccination during pregnancy, especially those at risk for severe infection (see Influenza).

However, it also recommended that pregnant women with certain medical conditions that increase their risk for complications should be vaccinated before the influenza season regardless of trimester.

Upcoming 2021-2022 Influenza Season:

The CDC published guidance for the upcoming 2021-2022 influenza season on August 26, 2021:

"Vaccine should be ideally administered by the end of October, but should continue to be offered as long as influenza viruses are circulating locally and unexpired vaccine is available."

"Persons who are pregnant or who might be pregnant during the influenza season should receive influenza vaccine."

"Any age-appropriate IIV4 or RIV4 [inactivated or recombinant] may be given in any trimester."

"LAIV4 [live-attenuated] should not be used during pregnancy but can be used postpartum."

"IIIV4s and RIV4 may be administered concurrently or sequentially with other live or inactivated vaccines."

"Providers should refer to current CDC/ACIP recommendations and guidance for the use of COVID-19 vaccines for up to date information on administration of these vaccines with other vaccines."

COVID-19

Read detailed information on COVID-19 vaccination here.

Tdap

The tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap) vaccine during pregnancy effectively passes antibodies of these diseases to the fetus before delivery.

Diphtheria: is an infection of the nasal, pharyngeal, laryngeal, or other mucous membranes that can cause nerve and heart muscle inflammation, platelet deficiency, and ascending paralysis.

Tetanus: causes production of a neurotoxin that is often fatal; symptoms include painful muscle contractions of the jaw and neck; neonatal tetanus may occur in newborns who have low levels of anti-tetanus antibody due to a lack of passively transferred antibodies from the mother.

Pertussis: also known as whooping cough, is a highly contagious respiratory infection most severe in infants or in individuals who have never been immunized against the disease; the infection can last 6 to 10 weeks and cause a “whooping” sound when an infected individual breathes in.

Whooping cough (pertussis) is a life-threatening disease for newborns; up to 20 infants die each year in the U.S. due to pertussis, and about half of infected infants younger than twelve months old require hospitalization.

Since the 1980s, pertussis has been on the rise in the U.S. In 2012, CDC saw the most cases in 60 years; of the 48,277 reported cases, 2,269 of those cases were in infants younger than three months old and 15 infants died.

It is unclear if the resurgence may be due to a mutation in the bacteria, improved diagnostic testing and increased reporting, or rapid waning of vaccination immunity (antibodies).

Most pertussis deaths are infants who are too young to be protected by the childhood pertussis vaccine. Infants do not begin their own vaccine series against pertussis until approximately two months of age. This leaves a window of significant vulnerability for newborns, many of whom may contract the disease from close family in the first few weeks of life. It is estimated that 47% to 60% of infected infants are exposed to the disease from their parents.

In 2006, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the CDC recommended a practice known as “cocooning” and this method has been adopted by various additional organizations. Cocooning involves administering the Tdap to previously unvaccinated family members and those expected to be in close contact with the newborn at least two weeks before the baby is born.

However, the best recommendation for the most optimal protection is vaccination of the mother during pregnancy:

Due to the 2012 outbreak, CDC and many other organizations recommend all pregnant women receive the Tdap vaccine, regardless of their last booster, during their third trimester of each pregnancy (ideally between weeks 27 and 36) for the most optimal protection of the newborn.

Further, if a woman has not been vaccinated with Tdap recently, or did not receive one during pregnancy, she should receive one in the immediate postpartum, to prevent her from passing pertussis to her infant.

However, if a pregnant woman requires the Tdap vaccine due to the prevention of a wound infection (tetanus) during pregnancy, she should be given the vaccination regardless of gestational age and should not receive a second vaccination during the third trimester.

The Tdap vaccine during pregnancy is effective (even in infants born preterm) and has an established safety record.

Although Tdap is a combination vaccine, it is has been estimated the tetanus toxoid vaccine alone was administered to 100 million pregnant women around the world in 2011. The safety of widespread tetanus toxoid vaccine use over the past 40 years, and the substantial decrease in neonatal tetanus supports the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine.

A study published in August 2021 assessed the effectiveness of the vaccine in producing antibodies. Recently vaccinated women had significantly higher Pertussis antibody titers (even 12–15 times as high) compared to those vaccinated more than 5 years before or never vaccinated at all.

A study published in April 2021 assessed the relationship between maternal Tdap vaccination and obstetric and perinatal outcomes in Ontario. Of 615,213 infants (live births and stillbirths), 11,519 were exposed to Tdap vaccination in utero. Study results indicated maternal Tdap vaccination is not associated with adverse outcomes in mothers or infants.

A clinical trial of the Tdap vaccine for mothers and infants was completed in 2014. The preliminary safety assessment did not find an increased risk of adverse events among women who received Tdap vaccine at 30 to 32 weeks’ gestation or their infants. Further, maternal immunization resulted in high concentrations of pertussis antibodies in the infants during the first two months of life.

A study published in April 2021 described the pertussis morbidity and mortality trends in infants less than or equal to 2 and 12 months of age, before and after maternal Tdap immunization implementation in Mexico (that started in 2013). After maternal immunization was implemented, there was a decreasing trend in incidence, hospitalization and death due to pertussis in infants 0-2 months old.

Breast milk antibodies: Clinical trial results published in September 2021 found that maternal Tdap vaccination induces high antibody levels in breast milk after both term and preterm delivery and that these antibodies remain abundantly present throughout lactation, possibly offering additional mucosal protection during the most vulnerable period in early life.

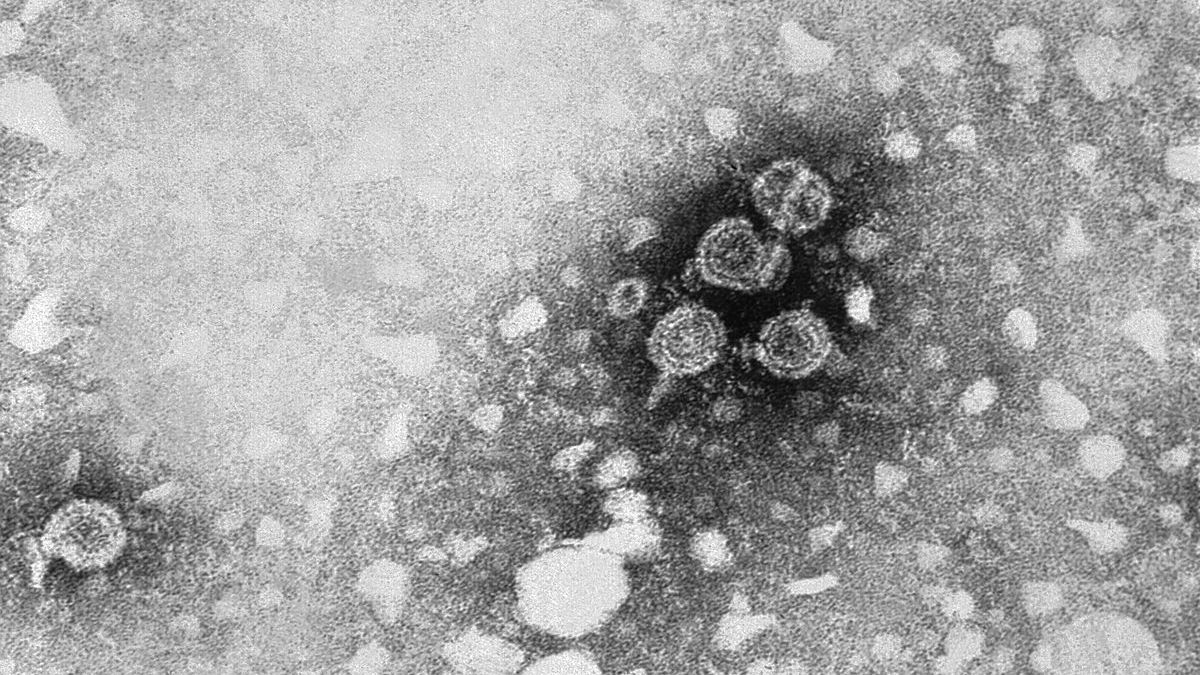

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B is an acute liver infection caused by a virus. It is transmitted through contact with infected blood, sexual activity, and sharing of intravenous needles. A baby whose mother has hepatitis B is considered high-risk of becoming infected with hepatitis B during vaginal delivery.

It is recommended that all pregnant women be screened for hepatitis B during standard early prenatal care; although most newborn infections occur during delivery, transmission during pregnancy has occurred, especially when a pregnant woman contracts a primary (first) infection late in pregnancy.

Pregnant women may be considered at risk for infection if they are having sex with a man who has sex with men, have multiple sexual partners, are using or abusing intravenous drugs, have occupational exposure, or are a household contact of an infected person (through any body fluid). A series of three vaccines is considered highly effective, providing an indefinite protective antibody response in greater than 90% of those vaccinated.

Women who believe they may be at risk for Hepatitis B infection during pregnancy should talk to their HCP.

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A is an acute liver infection contracted by approximately 100,000 persons annually in the U.S. It is acquired via the fecal-oral route by person-to-person contact or ingestion of contaminated food or water; therefore, the general public is considered to be at risk for infection.

While there is insufficient safety data regarding a Hepatitis A vaccine during pregnancy, it is an inactivated vaccine and is not expected to cause harm or an infection. It is recommended pregnant women receive the vaccination if they are at risk of contracting Hepatitis A infection.

Women may be at increased risk if they have direct contact with someone who has Hepatitis A, they travel to a country where the infection is common, they use intravenous drugs, or have a clotting disorder.

Women who believe they may be at risk for Hepatitis A infection during pregnancy should talk to their HCP.

Pneumococcal

The pneumococcal vaccine helps prevent any infection from streptococcus pneumoniae bacteria, which can cause mild to severe respiratory infections, as well as ear infections, pneumonia, septicemia, and meningitis. However, there is currently insufficient evidence to routinely recommend the vaccine during pregnancy for either the mother or infant.

The ACIP currently recommends that women at high-risk be vaccinated before, but not during, pregnancy. The safety of the pneumococcal vaccine during pregnancy has not been evaluated, although no adverse effects have been reported in newborns whose mothers were inadvertently vaccinated.

According to the CDC, risk factors for pneumococcal infection include decreased immune function from disease or drugs, abnormal function of the spleen, chronic heart, lung (including asthma), liver, or renal disease, cigarette smoking, cerebrospinal fluid leak, or a cochlear implant (due to increased risk of meningitis).

Measles, Mumps, and Rubella (MMR)

The MMR vaccine is a live attenuated vaccine that protects against measles, mumps, and rubella. It is not recommended during pregnancy, although it is recommended in the immediate postpartum period if an HCP determined the woman requires a booster shot.

Breastfeeding is not a contraindication for postpartum vaccination since any attenuated rubella virus excreted in breast milk and transmitted to the neonate results in asymptomatic infection.

Measles: a highly contagious disease that can cause complications such as ear infections, diarrhea, pneumonia, and encephalitis; measles is most often recognized by its wide-spread rash all over the body; measles can be passed to the baby during pregnancy, even with maternal asymptomatic infection.

Mumps: a contagious disease caused by a virus; symptoms include fever, headache, muscle aches, tiredness, and loss of appetite; most commonly recognized by swelling of the salivary glands, causing puffy cheeks and a tender, swollen jaw.

Rubella: contagious viral infection that can cause rash and fever in children and adults, but can be devastating during pregnancy, leading to congenital rubella syndrome; rubella during pregnancy can cause miscarriage, stillbirth, serious birth defects, or life-long illness in the child; ideally, HCPs test for a woman’s antibody levels (titer) at a preconception appointment.

As MMR is a routine vaccine, women should not be concerned if they were inadvertently given the vaccine while pregnant, or if they were unaware they were pregnant at the time of the vaccine. The caution against its use during pregnancy is largely theoretical; further, it is not routine for HCPs to have women take pregnancy tests prior to vaccination.

Varicella/Chickenpox

The varicella zoster virus causes chickenpox, which rarely leads to serious complications. However, chickenpox infection during pregnancy can cause severe illness in both mother and baby. Ideally, HCPs will test for antibodies at a preconception appointment; if the vaccine is required, it usually consists of two doses. It is further recommended that women wait approximately four weeks after vaccination before trying to get pregnant.

However, if a woman was inadvertently vaccinated during pregnancy, estimated risks to the fetus are considered very small.

Yellow Fever, Typhoid, and Japanese Encephalitis

Three frequently encountered travel-related, vaccine-preventable diseases are Japanese encephalitis, yellow fever, and typhoid fever.

Japanese encephalitis (JE) is a mosquito-borne illness and leading cause of viral encephalitis in Asian countries, with one quarter of cases estimated to be fatal, with neurological complications in up to 50% of survivors. Serious illness presents with sudden onset of fever, headache, vomiting, muscle weakness, movement disorders or acute paralysis, and seizures.

Travelers to rural parts of Asia have an increased risk of acquiring JE infection, which is estimated at approximately 1 in 5,000 per month. In short-term travelers to urban areas, risk of infection is estimated at less than one per million.

There are no adequate studies of the vaccine during pregnancy, and the vaccine is not recommended unless the woman is considered at high-risk for infection. High-risk includes longer-duration travel to endemic areas, in which the risk of infection may outweigh the possible risks of vaccination.

Yellow fever is a viral hemorrhagic fever syndrome spread by mosquitoes in parts of South America and Africa. Common symptoms include fever and headache with less common symptoms including light sensitivity, joint and muscle pain, vomiting, and upper abdominal pain. Severe infection is associated with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, hemorrhage, and death.

There is no safety-related information regarding the yellow fever vaccine during pregnancy. As the vaccine is live attenuated, it is not recommended for pregnant women unless there is an epidemic or the woman is travelling to a high-risk area. At least one study documented inadvertent vaccination of pregnant women and demonstrated no association with toxic effects, miscarriage, or preterm birth.

Typhoid fever is a life-threatening disease caused by the bacterium Salmonella typhi and is responsible for approximately 5,700 cases each year in the U.S., about 75% of which are associated with international travel. Infected individuals usually present with fever, fatigue, and headache, while severe disease is associated with intestinal hemorrhage and death.

Most cases of typhoid fever occur in travelers who recently have returned from high-risk areas, such as South America, India, and western Africa, or moderate-risk areas, such as Mexico, Haiti, northern Africa, and Iran.

The two types of typhoid vaccination in use today are a live attenuated oral vaccine and a parenteral polysaccharide vaccine. Both forms require that immunization be completed at least two weeks before exposure. Unfortunately, there are no data supporting the efficacy and safety of either vaccine in pregnancy, and CDC has made no specific recommendations regarding these vaccines during pregnancy.

In Development (RSV/Group B Strep)

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a major cause of serious, potentially fatal respiratory infection in infants, but no preventive vaccine is available; up to 60% of infants will contract RSV during their first season of exposure.

While research is ongoing regarding a vaccine for infants and young children, this research also includes a vaccine that could be administered to pregnant women that would pass antibodies to the infant even before birth (read Respiratory Infections for more information regarding RSV infection during pregnancy). As of July 2021, numerous clinical trials are underway.

One profile of the the RSV F recombinant nanoparticle vaccine was published in May 2021. The vaccine was safe and well tolerated in pregnant women and the results suggested potential benefits, but it did not meet the success criteria for efficacy against RSV-associated, respiratory tract infection in infants up to 90 days of life. Therefore, research remains ongoing.

RSV in infants cases started climbing around the U.S. in July 2021, spurring at least one state (Texas) to recruit pregnant women for an RSV vaccine trial.

Group B strep (GBS) is the leading cause of invasive infection during the first 90 days of life and is the predominate cause of neonatal sepsis and meningitis, even with preventative antibiotics during labor (read Group B Strep for more information).

A GBS vaccine has been theorized to potentially be a more effective and reliable way to prevent both early- and late-onset disease in newborns/infants. As of June 2020, at least one vaccine was currently in phase II, and one vaccine had completed phase II with promising results.

Action

It is recommended that every pregnant woman be vaccinated with the Tdap and seasonal influenza vaccines.

Pregnant women who have certain risk factors, or travel to endemic areas, or areas with high rates of certain infections may require additional vaccines.

Women who have any questions or concerns regarding these vaccines should talk to their HCP or see Resources for more information.

Partner/Support

Partners, family members, and friends should seriously consider getting vaccinated with the Tdap vaccine at least two weeks before expected delivery of the baby (or when the pregnant woman receives hers) if they have not received a booster within the last 10 years. Partners/family members should ask their HCP about their vaccination history and request a booster if necessary.

Resources

How Vaccines Work (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

How Vaccines are Made (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

COVID-19 Vaccination of Pregnant or Lactating People (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

Vaccine Recommendation Chart (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

FDA Presentation Materials regarding Group B Strep (May 2018): FDA Website (Scroll down to the bottom)

Maternal Immunization: Committee Opinion 741 (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; June 2018)