Cervix

The cervix undergoes remarkable changes during pregnancy, from changing in color, to strengthening and lengthening, only to reverse at the end of pregnancy and soften, thin, and dilate.

The cervix remodels once again in the postpartum period to allow for additional pregnancies.

The cervix’s inability to either strengthen, efface and dilate, or return back to normal can lead to numerous complications. However, some of these complications can be effectively identified, treated, and prevented during current and future pregnancies.

Women who have any concerns regarding their cervix during pregnancy, to include its ability to retain a pregnancy, or their risk of preterm delivery or possible infection, should to have a discussion with their HCP.

Background

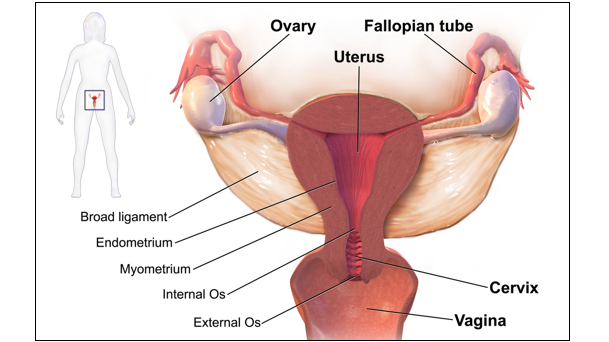

The cervix is the opening to the uterus that sits at the top of the inside of vagina. It is the lower, cylindrical portion of the uterus that has small openings at each end and separates the uterus and vagina.

These openings are blocked during pregnancy (mucus plug), which then dilate during labor and delivery and the “physical” part of the cervix is what effaces (thins out).

The opening of this canal into the uterus is called the internal os and the opening into the vagina is called the external os. The structure and function of the internal os is considered most critical during pregnancy.

Nonpregnant cervix (image below): closed and firm, consistency is similar to nasal cartilage; about 2.5 to 4 cm in length and about 2.5 cm in diameter (full diameter, not the opening); these measurements can change based on age, number of births, and phase of menstrual cycle.

Menstrual cycle: there is cervical anatomic variation depending on cycle state; the cervical canal is at its widest and longest near and after ovulation to allow for the passage of sperm.

Pregnant: in early pregnancy, the cervix softens to a consistency similar to "lips" and turns slightly bluish in color (or purple-red); it then strengthens and remains firm and closed until the third trimester, where it becomes softer near delivery; length of 30 to 40 mm.

Pregnancy

The firmness of the non-pregnant cervix is due to collagen, which rearranges and remodels itself to strengthen and retain a pregnancy. The cervix completely reverses this process at term to soften, efface, and dilate for delivery. Finally, it remodels once again in the postpartum period to allow for additional pregnancies. The biomechanics of exactly how the cervix does this is still being studied.

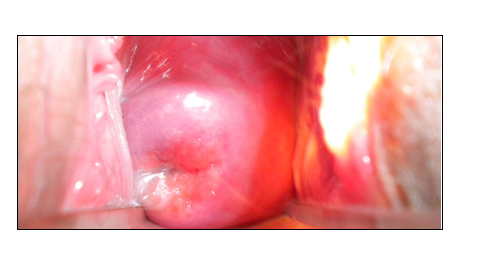

As early as 6 weeks of pregnancy, the cervix begins to gain bluish or red-purplish tones (Chadwick’s sign, see photo) due to increased blood vessels and fluid/swelling of the entire cervix. These cervical color changes were first described in 1895 and were once used to diagnose pregnancy.

These additional blood vessels are also assessed to be the reason for light vaginal bleeding/spotting after sex, especially if contact is made with the cervix; however, some research debates whether this occurs due to sex (read Bleeding).

The cervix produces mucus that is regulated by estrogen and progesterone. During ovulation, this mucus has a stretchy and stringy consistency (known as spinnbarkeit) to help sperm travel through the cervix and into the uterus. This mucus changes during pregnancy:

Cervical mucus looks different under a microscope when a woman is pregnant versus when she is not pregnant. Non-pregnant cervical mucus looks like a “fern” pattern due to the presence of estrogen. Pregnant cervical mucus is “beaded” or “cellular” due to progesterone.

The pregnant cervix also produces a mucus plug – an abundant amount of thick mucus to obstruct the cervical canal soon after fertilization. This blocks any harmful microbes/bacteria from invading the lower genital tract and causing infection.

The function of the cervix at this point is to strengthen and remain closed, despite multiple forces acting upon it, especially as pregnancy progresses.

Further, as the fetal membranes are in direct contact with the internal os, the cervix needs to maintain incredible strength to avoid descent of the membranes into the cervical canal, which could dislodge the mucus plug, leading to preterm delivery.

Cervical measurement is taken by transabdominal ultrasound at or after 16 weeks, to assess for any potential cervical failure. The length of the cervix can be affected by infection, a very enlarged uterus, bleeding, or inflammation.

As the body gets ready for labor, the cervix decreases in length, softens, becomes thinner (effaces), and finally opens (dilates) to allow for delivery.

Near the end of pregnancy, the discharge may contain streaks of thick mucus and/or blood as the cervix thins out and prepares for delivery. This is likely the dislodging of the mucus plug, which could be gradual, or all at once.

Dilation and Effacement

Dilation (10 cm) and effacement (100%) must occur before the baby can pass through the birth canal for delivery. This process cannot take place until cervical ripening occurs, which can start hours, days, or weeks before labor.

Dilation and effacement occurs simultaneously, but effacement usually completes first. As the cervix effaces, this causes the expulsion of the mucus plug, rather than dilation (read Dilation and Effacement).

Postpartum

Just like the uterus, the cervix contracts in the postpartum period to help it narrow. Within minutes after delivery, the cervix actively closes at the internal os, while the external os can stay dilated for hours,days, or even weeks.

This has recently (2019) led some researchers to advocate for further study into the internal os, indicating the internal os may act more like a sphincter because it is able to close very quickly compared to the external os.

This would be a progressive shift in how the cervix is assessed to cause preterm delivery, and could result in newer treatment or management strategies. Note: Current thought suggests the cervix has the same properties throughout, with no structural differences between the internal os and external os.

Before childbirth, the external os is a small regular oval opening. After dilation and effacement, and especially after vaginal delivery, the opening becomes more like a transverse slit. If torn during labor, the cervix may heal in such a manner that it appears irregular or nodular, but still retains its strength.

This image contains triggers for: Internal Anatomy

You control trigger warnings in your account settings.

Action

Women who have any concerns regarding their cervix during pregnancy, to include its ability to retain a pregnancy, risk of preterm delivery, or possible infection, need to have a discussion with their HCP.

Some HCPs may perform a pap smear during an early prenatal appointment, but not always. Read more information on pap smears during pregnancy here.