Gestational Diabetes

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) is a condition in which a pregnant woman’s pancreas does not produce enough insulin to regulate blood glucose levels, putting the woman and her baby at risk for hyperglycemia (high blood sugar).

GDM only occurs during pregnancy because the actions of the placenta are the cause; therefore the condition goes away almost immediately after delivery, once the placenta is removed.

The placenta produces hormones that block insulin – this is considered normal. Most women will be able to overcome this through the production of additional insulin by the pancreas. Other women do not adjust to this increased requirement and will be diagnosed with GDM as a result.

For most women, GDM can be controlled with a specific diet, regular physical exercise, and continuous blood glucose monitoring; some women may also be required to take insulin.

Uncontrolled GDM can have complications for both mother and baby. Women need to be screened around 24 to 28 weeks of pregnancy, when this resistance has reached a peak high enough to be caught through a glucose challenge test.

Women diagnosed with GDM need to follow instructions exactly as provided by their health care provider (HCP) and talk to their HCP if they have any questions.

Background

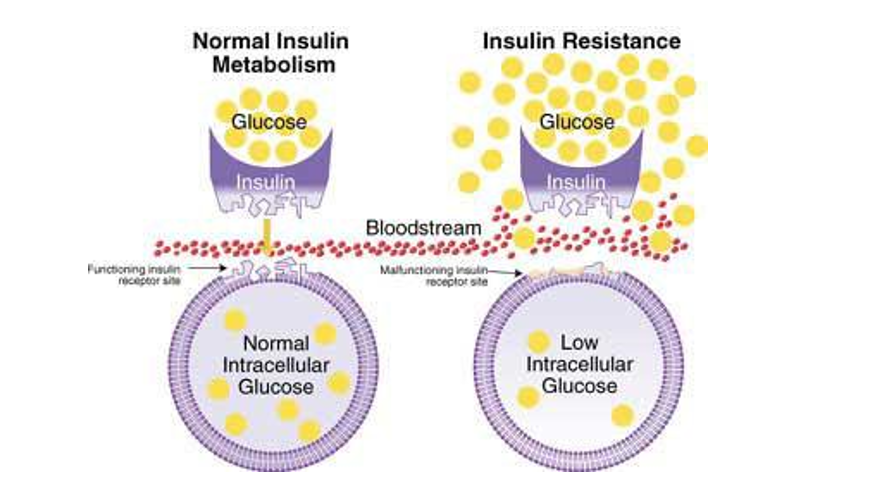

After a meal, sugar (glucose) is released into the bloodstream; the amount of sugar released depends on the meal. The pancreas releases insulin (a hormone) to help move glucose from the bloodstream into the body's cells to be used as energy.

The higher the sugar content of a meal, the higher the insulin requirement. If the pancreas does not produce enough insulin, glucose in the blood builds up (high blood sugar) and causes numerous complications.

Type 1 Diabetes: a type of autoimmune condition in which the pancreas produces little to no insulin

Type 2 Diabetes: the pancreas produces insulin, but does not produce it properly

Hyperglycemia: high blood sugar; when severe, and left untreated (insulin), leads to life-threatening complications

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM): a woman is diagnosed for the first time with diabetes during pregnancy; considered an early sign of type 2 but is usually temporary and goes away after delivery; however, it remains a risk factor for developing type 2 after pregnancy

Hypoglycemia: low blood sugar; when severe and left untreated, leads to life-threatening complications; occurs often in diabetic patients who take too much insulin

Note: Diabetes Insipidus is a rare condition that causes fluid imbalance within the body and results in symptoms such as extreme thirst and very frequent urination. This is a separate condition than those described above and is not related to insulin. Read more here.

The prevalence of GMD may be as high as 10% of all pregnancies in the United States.

Insulin Resistance in Pregnancy

Hormones from the placenta block the action of the mother's insulin in her body – this is normal during pregnancy and is known as insulin resistance.

Insulin resistance makes it harder for the mother's body to use insulin. The pancreas may need to produce three times as much to overcome this resistance. Further, If a woman was taking insulin prior to pregnancy, she may also require up to three times as much.

As the fetus continues to grow, the placenta produces more and more insulin-counteracting hormones, with peak resistance beginning around mid-pregnancy. This resistance may not affect most women until about 20 weeks of pregnancy; therefore, women are tested at 24 to 28 weeks, and not before. However, women considered at high-risk for GDM may be tested earlier.

Normally, the pancreas adjusts to this resistance and has no problem producing more insulin. The development of GDM occurs when a woman’s pancreas does not secrete enough insulin and glucose in the blood builds up. This buildup can be observed in the blood of pregnant women after 20 weeks but usually does not produce symptoms.

A study published in July 2021 found that GDM with insulin resistance in the second trimester increased adverse pregnancy outcomes, especially the risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (high blood pressure, preeclampsia) and large-for-gestational-age.

Fortunately, GDM generally does not cause birth defects that are sometimes seen in women with pre-existing diabetes, mostly because of its later development, after the fetus’ organs have formed.

Since the placenta is the organ producing the hormones that block insulin, GDM is usually “cured” after delivery with the removal of the placenta.

Risk Factors

Researchers don't know why some women develop GDM.

Being overweight or obese is linked to gestational diabetes mostly because these women likely already have some form of insulin resistance prior to pregnancy, which is then compounded during pregnancy.

Additional risk factors include:

Family history of diabetes

Personal history of diabetes, including GDM

Previously giving birth to a baby that weighed more than 9 pounds

Previously giving birth to a stillborn baby

Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome

Vitamin D deficiency (preliminary research)

Women assessed to be at risk for GDM by their HCP may be screened at their first prenatal appointment and again at mid-pregnancy (if the first test was negative).

Complications – Mother

Most women with controlled GDM continue to have healthy, full term pregnancies. If complications do occur, delivery may be recommended, depending on gestational age and the health of the baby.

Uncontrolled blood sugar levels during pregnancy can increase the risk of:

High blood pressure and preeclampsia (strongly linked)

Future diabetes

A large baby (9 pounds or more)

Heavy bleeding/severe tearing after delivery (due to a large baby)

GDM and preeclampsia have several mechanisms in common and GDM is itself a risk factor for preeclampsia:

Preeclampsia is assessed to be a condition of the blood vessels. High glucose concentrations can inhibit trophoblast invasion, in which the placenta and uterus make a complete connection through the growth of blood vessels known as spiral arteries.

When this connection fails, the placenta does not get enough blood and/or oxygen (ischemia). Studies show that GDM promotes placental ischemia, but how it does this is not understood.

Complications – Baby

Extra glucose in the mother’s blood goes through the placenta into the baby’s bloodstream which gives the baby high blood sugar. While the baby’s pancreas will produce extra insulin to counteract this, the baby is still getting more energy than needed and will store the rest as fat (babies born to mothers with GDM may be 9 pounds or more at delivery, known as macrosomia).

Babies with macrosomia can damage their shoulders, collarbones, or nerves during birth, and may receive inadequate oxygen during labor which could cause potential brain injury.

Babies with mother’s who have uncontrolled GDM may also be at risk for:

Preterm birth and respiratory distress syndrome (especially if the baby needs to be born right away)

Low blood sugar – the baby’s pancreas is producing so much insulin that the baby’s blood sugar is dangerously low at birth which can cause life-threatening complications, including seizures (requires immediate glucose/feeding).

Diagnosis/Management

It is recommended all pregnant women should be screened for GDM by 28 weeks of pregnancy through a glucose drink and blood test. Those considered high-risk are screened at the first appointment.

Treatment for GDM aims to keep blood glucose levels in a normal range by using lifestyle modifications first, followed by medication if necessary.

There are four main components of the management of GDM:

Healthy diet and exercise

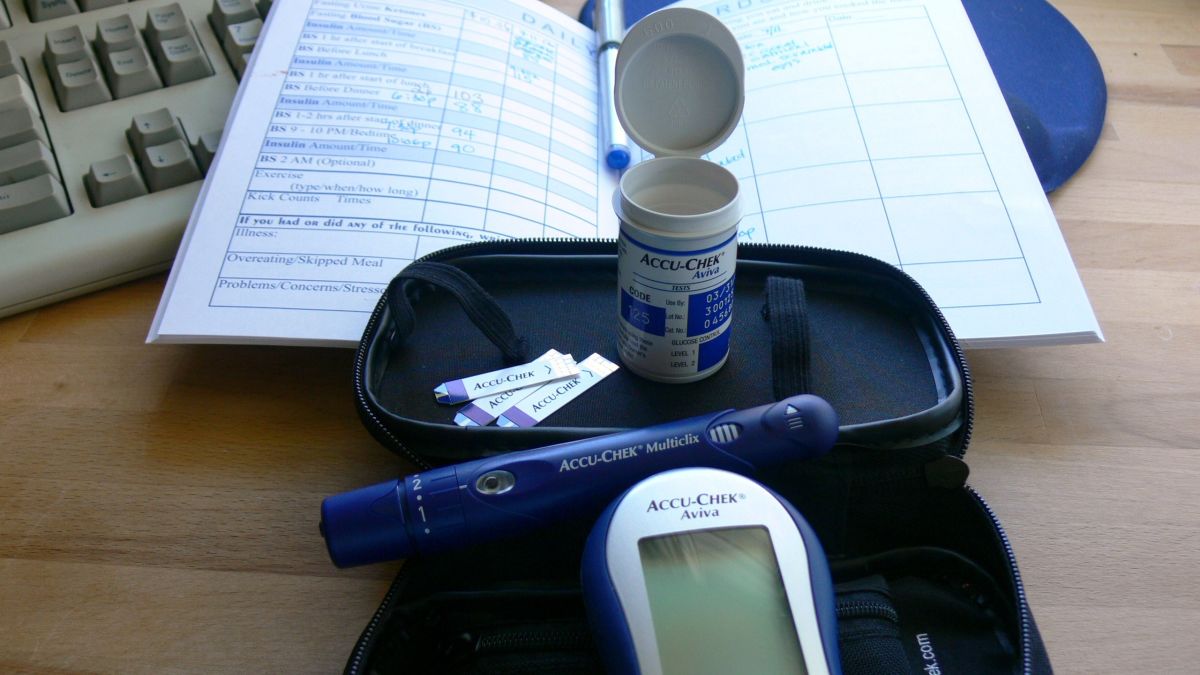

Blood glucose monitoring

Medication if necessary

Postpartum diabetes screening

The initial treatment of GDM consists of diet and exercise. Healthy, smart food choices and eating regularly can prevent a woman’s blood sugar levels from getting too high or too low. Women are also advised to avoid stress and smoking. Exercise may help the muscles use glucose more efficiently and help control blood glucose levels.

A review published in August 2021 indicated best outcomes may occur when physical activity is performed for a minimum of three times per week, at least at moderate intensity, and should be based on aerobic, resistance and strength exercises (women should speak with their HCP first before starting any exercise program).

Women with GDM may also be asked to reduce their carbohydrate intake while making sure they still get enough fiber. Carbohydrates increase blood sugar levels quickly; eating too many carbohydrates can cause fast weight gain in women with GDM (Note: this does not occur in women without GDM; carbohydrates are a necessary source of glucose during pregnancy. Women should not avoid carbohydrates during pregnancy for fear of weight gain or having a large baby; read more).

Women with GDM may have to check their blood sugar up to five times per day or more – first thing in the morning and after each meal.

There are many blood sugar devices available. Traditional devices require a small drop of blood placed on a test strip that is then inserted into the device which displays the blood sugar level. Ideally, levels should be:

Before a meal: 95 mg/dl or less

1-hour after a meal: 140 mg/dl or less

2-hours after a meal: 120 mg/dl or less

The American Diabetes Association suggests the following targets for women with pre-existing diabetes who become pregnant:

Before a meal and bedtime/overnight: 60-99 mg/dl

After a meal: 100-129 mg/dl

A1C: less than 6%

Women may be asked to keep a record of their blood sugar levels and provide them to their HCP at each prenatal visit; various apps are available which can email results.

Up to 39% of women with GDM cannot meet glucose targets through diet and exercise alone and will require insulin. Insulin is the traditional first-choice drug for blood glucose control as it does not cross the placenta.

Prior to the discovery of insulin in 1921, GDM was considered a fatal condition for both mother and baby.

However, insulin is relatively expensive and can be difficult to administer; women who require insulin injections need to learn the correct way, timing, and dose from their HCP and follow instructions exactly. Too much insulin can result in hypoglycemia.

Researchers are studying the safety of metformin and glyburide during pregnancy, but more research is necessary before recommendations can be made.

The role of chromium supplementation in gestational diabetes is being studied but is not currently recommended as a management method due to mixed results. Further, it could affect the amount of insulin needed.

The hypothesis that chromium supplementation can help with glucose tolerance in diabetes is popular, based on individuals who developed diabetes when they had no chromium in their diet. Their condition was essentially cured when given chromium supplementation.

However, these results have not translated to individuals with diabetes who have no chromium deficiency, and chromium has very little effect on glucose tolerance in those cases.

Women should not take any over-the-counter supplements during pregnancy without first speaking with their HCP.

Postpartum

It is advised, however, that women who had GDM have their levels checked again between 4 and 12 weeks postpartum. If the screening is negative, it is further advised to get re-screened every 1 to 3 years. Approximately 20% to 60% of women who had GDM will develop type 2 diabetes within five to ten years; the reasons for why women who had GDM are at such high postpartum risk for type 2 diabetes is not known.

It is possible that GDM may also be a risk factor for future heart disease. A study published in February 2021 of more than 2,700 women suggests GDM increased the risk of coronary artery calcification later in life, regardless of glucose control following pregnancy.

In addition, a study published in August 2021 found that among 906,319 eligible women in Ontario with a GDM diagnosis and a live birth delivery between 1 July 2007 and 31 March 2018, there were 763 heart failure events over a median follow-up period of 7 years. GDM also increased the odds of peripartum cardiomyopathy (weakening of the heart muscle near delivery and through five months postpartum).

It is recommended that women diagnosed with GDM during pregnancy continue to inform their health care providers – to include up to 10 years after pregnancy – that they had this diagnosis.

Knowledge of this risk factor may help women prevent cardiac/metabolic problems years after pregnancy (or be diagnosed/treated earlier).

Action

All women should be screened for GDM during 24 and 28 weeks of pregnancy, or as directed by their HCP. Women who are considered high-risk for GDM may be screened much earlier. Detailed information regarding the glucose screening test can be read here.

Women should direct all questions or concerns they have regarding GDM and GDM screening to their HCP.

Women should also consider sharing and submitting their experience below regarding gestational diabetes. This can help women positively learn from other women who are going through the same thing.

Resources

Gestational Diabetes (American Diabetes Association)

Gestational Diabetes (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists)

Gestational Diabetes (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases)

Gestational Diabetes Leaflet (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists)