Causes and Contributing Factors

The development of Nausea and Vomiting of Pregnancy (NVP) is currently assessed to be multifactorial, and different women will experience different combinations of these factors, which is why symptom severity is so variable among women.

To date, this is likely the main explanation no "optimal" treatment method has been found for all women (i.e. some women find B6 or ginger helpful, while others find no relief).

Regarding specific causes, there is conflicting data for almost all hypotheses of the pathogenesis of NVP. Further, popular theories from decades past have almost no evidence in more modern research. The biggest change from the last few years includes the shift away from human chorionic gonadtropin (HCG) as the main primary cause and toward specific genes and combinations of factors.

Complicating this issue is that the assessed potential causes, contributing factors, symptoms, and complications of NVP are similar and overlap because what causes NVP vs. what does NVP cause has not been clearly determined or defined.

This page is lengthy; causes and contributing factors need to be assessed and presented together to understand how current research affects management options. Use the menu bar below (mobile) or left (desktop) to ease viewing.

Background

Researchers do not know what specifically causes NVP because the answer is complex. The physiological processes of nausea and vomiting are very difficult to understand in non-pregnant individuals, let alone pregnant women.

Further, the assessed potential causes, contributing factors, symptoms, and complications of NVP are similar and overlap because what causes NVP vs. what does NVP cause has not been clearly determined or defined.

The effective management of one or more may provide much needed relief of others. Therefore, women need to learn about these factors, and assess – with the help of their health care providers (HCP) – what may be causing or contributing to their symptoms. Some of these factors can be adequately managed, which could provide significant symptom relief overall (read Management).

Hormones

Estrogen, progesterone, and human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) are most often implicated in the pathogenesis of NVP, but current research appears to be steering away from hormones and toward other factors.

Hormones were – and still are, but to a lesser extent – the most popular theory for several obvious reasons:

The menstrual cycle and its variations of hormone levels can cause some of the same symptoms experienced in early pregnancy, including nausea.

Women who use hormonal contraception or hormone replacement therapy not only experience nausea, but are more likely to experience nausea during pregnancy (estrogen may activate the vomiting center in the brain).

Women pregnant with more than one baby have higher hormone levels and tend to experience more severe NVP than women pregnant with only one baby.

Women with low or high estrogen levels are associated with an increased risk of hyperemesis gravidarum, which indicates a hormonal imbalance may predispose to severe nausea/vomiting.

Women pregnant with a girl may be more likely to experience NVP, thought to be due to increased estrogen levels.

However, even though the above correlations are logical, studies assessing the above risk factors are inconsistent, and estrogen levels peak in the third trimester, while NVP tends to improve in the second trimester. Further, there has been a lack of strong evidence indicating a difference in estrogen levels between pregnant women with or without NVP. It is possible some women may just be more sensitive to the effects of hormones, but this is inconsistent as well.

It is significantly more likely this inconsistency is due to so many other factors also affecting NVP, rather than only hormones.

Progesterone is most often cited as causing gastrointestinal (stomach) dysmotility and dysrhythmias which can lead to NVP.

It is largely believed that progesterone inhibits the ability of the stomach and intestines to contract; therefore they “move” slower, and food remains in the GI tract longer, causing nausea and/or reflux. This is very controversial, and numerous studies have found no change in motility during early pregnancy (also see Digestive Factors, below).

Progesterone was also thought to cause NVP based on the timing of placental development. Progesterone is secreted by the corpus luteum immediately after implantation until the placenta takes over this role, estimated to be at any point between 7 and 12 weeks of pregnancy. Since the later end of this range was thought to be when most women began to feel better, progesterone appeared to have a significant role.

However, based on more recent statistical analysis of temporal NVP data, NVP tends to peak around 9 and 10 weeks, the exact time frame in which the placenta should be starting the "transfer" process. Further, most women do not begin to feel better until closer to 16 to 20 weeks.

Additionally, while some studies have found higher progesterone levels in women with NVP, other studies have found no association.

HCG is a hormone produced by the trophoblasts of the developing placenta. After implantation, the embryo actively secretes HCG, which can be detected in the mother’s blood as early as 8 days after ovulation. HCG lets the body know a pregnancy has occurred and the rest of the body begins changing to support it.

For decades, high HCG levels have been linked with NVP. Recent research is stepping away from HCG as a cause of NVP, with HCG possibly playing only a minor role. Prior links were inconsistent and mostly coincidental, based on the time NVP begins/peaks and HCG levels peak.

Additionally, although women with multiple pregnancies and molar pregnancies are more likely to experience severe nausea and vomiting due to higher HCG levels, these are only considered risk factors, as many women with these conditions do not experience NVP.

Current research indicates there is no evidence to support HCG as a primary factor and many studies have not found a correlation between high-HCG levels and NVP. Further, the first genome-wide analysis of Hyperemesis Garavidarum (HG), the most severe form of NVP, (March 2018) gave no support to the role of HCG (or estrogen) in NVP.

Central Nervous System

Regardless of the exact hormonal pathway to NVP, primary involvement of the central nervous system (CNS) is evident. Progesterone, estrogen, HCG, and luteinizing hormone are all assessed to activate the vomiting center, as these hormones all have receptors located in that region of the brain.

The vomiting center, the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ) of the brain, contains receptors that detect agents (i.e. various hormones) in the blood that can trigger vomiting. Receptors detect these agents, relay this information to the CTZ, and the CTZ then induces the vomiting reflex.

Antiemetics, such as antihistamines and ondansetron, work by blocking these receptors in the brain (other common medications for NVP work on the GI tract rather than the brain) (read Medications).

The exact mechanisms for how vitamin B6 relieves nausea in NVP is not known, but most of B6’s primary effects are on the CNS. Doxylamine, an antihistamine, is commonly used in combination with B6.

The way in which a pregnant woman responds to causal factors of NVP depends on her tolerance and susceptibility to nausea, which is controlled by vestibular (motion), gastrointestinal (stomach), olfactory (smell), and behavioral pathways.

A woman’s threshold for nausea may also change minute-to-minute depending on these factors, along with anxiety, panic, frustration, and other emotions that may further stimulate the CNS.

During early pregnancy, stimuli that initiate the nausea and vomiting processes are incredibly sensitive, and it does not take much to suddenly feel or become ill without warning.

The vestibular system, affected by hormones, stabilizes eye and head movements (motion sickness, migraine) as well as stability, and, in part, the sensitivity of any given individual to nausea/vomiting.

Women with NVP are more likely to report a history of motion sickness and migraine, and avoidance of motion is a common avoidance strategy for women with NVP.

Women with any history of migraines, other headaches, vestibular disorders, dizziness, and/or motion sickness should report this to their HCP. These types of factors may require more specific management methods that could lead to better relief of nausea and/or vomiting.

Specific Genes

In just the last few years, several studies have found specific genes that may be involved in the pathogenesis of NVP, and more specifically, HG.

A gene called Growth Differentiation Factor 15 (GDF15) and its receptor, GFRAL, were recently identified to activate the CTZ. GDF15, a major appetite suppressor, is secreted by a wide variety of cell types in response to a stressor, such as pregnancy.

In the non-pregnant state, GDF15 is expressed at low levels. In pregnancy, GDF15 is dramatically increased and rises rapidly in the first trimester, with high concentrations in the placenta and amniotic fluid.

The fact GDF15 rises so high during pregnancy, has an anti-appetite effect, and has receptors in the CTZ, has led some researchers to assess the gene could play a role in NVP.

In a study published in February 2022, GDF15 was the greatest genetic risk factor for HG, corroborating prior evidence. "GDF15 is most highly expressed by the placenta, increases significantly in the first trimester and activates the vomiting center" of the brain.

Two recent studies (March 2018; April 2019) identified and corroborated that GDF15 and another gene, IGFBP7, were associated with HG. This researched showed that both GDF15 and IGFBP7 were dysregulated in HG pregnancies when symptoms peaked, but not later in pregnancy when symptoms subsided.

In September 2018, another study showed increased serum (blood) GDF15 levels were significantly associated with both second trimester vomiting and antiemetic use during pregnancy (but interestingly, not HCG levels, as stated above).

These researchers assessed that since GDF15 has receptors in the CTZ, and women with HG have higher circulating levels in the their blood, that GDF15 and IGFBP7 may play a (possibly significant) role in vomiting during pregnancy. Further, HG is assessed to be genetic, and GDF15 may explain family cases, as well as the risk of recurrence.

HG is currently a diagnosis of exclusion, in which other conditions are usually ruled out prior to diagnosis. This research illustrates that serum levels of GDF15 and IGFBP7 may be useful in diagnosing HG in the future.

Researchers also noted that a significantly larger study is necessary to confirm findings, as well as to include pregnant women without NVP (as a control). If further confirmed, it is possible that treatment for HG can include medication that blocks GDF15 and IGFBP7 levels safely to minimize nausea and vomiting. Preliminary animals studies have already shown success.

Acid Reflux

*Overlaps with Heartburn/Acid Reflux (Symptoms and Conditions)

Acid reflux does not just affect a pregnant woman at the end of her pregnancy; it can be a major and surprising contributing factor for women with even mild NVP.

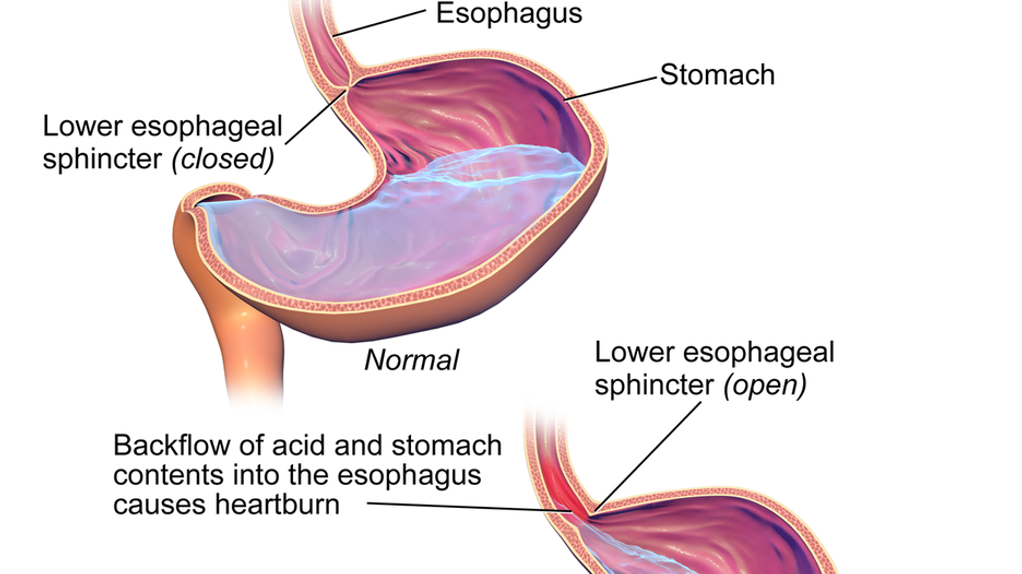

An increase in hormones early in pregnancy causes acid reflux due to a relaxation in lower esophageal sphincter pressure. This sphincter is located between the esophagus and stomach (see below image). When closed, it prevents food/acids in the stomach from traveling back up the esophagus. As progesterone relaxes this sphincter, foods/acids can more easily travel back up. In some cases, this can result in no other symptoms except for nausea and/or vomiting.

Note: Acid reflux is the cause of heartburn; heartburn is a symptom of reflux.

Acid reflux is a frustrating condition in early pregnancy, as reflux can cause nausea and vomiting, and nausea and vomiting can also cause acid reflux. It is also entirely possible some women do not actually have NVP, but are simply experiencing nausea in early pregnancy due to reflux.

Additional studies have shown that some women gain significant relief while taking antacids because their NVP appears to be aggravated by, or even completely caused by, acid reflux.

Further, at least one study showed that women with both NVP and heartburn and/or acid reflux had more severe nausea and vomiting than women without heartburn or acid reflux.

One particular study of women with HG determined 75% experienced heartburn and acid reflux, but only 24.7% were using acid-reducing medications.

Reflux can also cause foods to taste differently, exacerbating aversions that can lead to nausea. It can also lead to irritation of the upper esophagus, which easily triggers the gag reflex leading to gagging, coughing, and/or vomiting.

Signs and symptoms of acid reflux can include difficulty swallowing, acidic taste in the back of the throat, sore throat, hoarseness, wheezing, and chest pain — especially while lying down at night.

Women should call their HCP to be evaluated for acid reflux in early pregnancy, especially if experiencing moderate to severe NVP, and symptoms appear to be worse at night or when sleeping. This is important – some common management techniques for NVP can make reflux worse (i.e. ginger, citrus).

Treating heartburn and reflux problems may relieve symptoms of NVP and increase women’s overall well-being by improving nutrition, comfort, and sleep. Antacid medications can treat the symptoms of acid reflux whether as a cause of NVP, or the result of NVP. There are numerous medications available that are considered safe during pregnancy, to include during the first trimester (read more).

Digestive Factors

*Overlaps with Gastrointestinal Tract Changes (Body Changes)

Gastrointestinal (GI) changes create many significant symptoms during pregnancy, to include nausea, vomiting, acid reflux, heartburn, and constipation, all of which can make each other worse.

The most significant change to the GI tract regarding NVP appears to be motility, but this is also controversial. "Motility" is a term used to describe the contraction of the muscles that mix and push contents into the GI tract. However, researchers do not have a complete understanding of motility changes during pregnancy, and whether motility is actually affected in the first trimester is still debated.

As stated above, it is currently believed that progesterone inhibits the ability of the stomach and intestines to contract to some degree; this is one of the most frequent cited causes of NVP.

However, evidence is inconsistent regarding GI tract motility during pregnancy, and rate of emptying has only been partially studied. Part of this inconsistency is due to the limited methods researchers can use to measure emptying time, as the most accurate imaging techniques use radiation.

In studies that have documented reduced motility of the GI tract, it is theorized the GI tract relaxes slightly due to progesterone which allows for maximum absorption of vitamins and minerals, although it leads to nausea, reflux, and constipation as a result.

Other studies have documented no change in GI tract motility at any stage during pregnancy (except for during labor) and some found no correlation with NVP.

It is possible, however, that women with moderate to severe GI symptoms during pregnancy may be more affected by progesterone’s effects on motility than women without these symptoms. At least one study showed women with HG demonstrated prolonged gastric emptying in comparison to those without HG.

Nausea is also associated with dysrhythmias of the stomach. The stomach possesses pacemaker tissue (like the heart) which generates slow wave-like motions with set consistency. Dysrhythmias are disturbances of this pattern, either faster or slower, that are present in some women with NVP.

Progesterone and estrogen likely cause this disruption in some women, as researchers were able to replicate dysrhythmias by administering non-pregnant women either progesterone alone or in combination with estradiol in doses equal to pregnancy levels.

The hormone vasopressin also induces gastric dysrhythmias, which leads to nausea and vomiting in non-pregnant individuals. Vasopressin is increased in early pregnancy due to an increase in HCG.

However, the causal relationship between gastric dysrhythmias and motility of the GI tract are not understood and more research is necessary.

Women need to talk to their HCP if they have any diagnosed or underlying gastrointestinal illnesses or disorders that could increase their risk of severe NVP, or may be currently affecting their symptoms.

Fatigue

Fatigue is one of the most frequent and persistent complaints reported by pregnant women in early pregnancy, which is likely a major contributing factor to NVP.

Since NVP can cause fatigue, and fatigue can worsen NVP, it is often recommended that women try to manage their fatigue, along with their nausea. However, at least one study found that almost half of women in early pregnancy did nothing at all or "non-evidence based" actions to manage nausea, vomiting, or fatigue.

NVP and fatigue are directly associated, in both directions. Although NVP in the first trimester has numerous potential causes, fatigue has been shown to dramatically worsen nausea, and severe nausea worsens fatigue, which dramatically affects a woman’s ability to manage either symptom (similar to reflux and nausea).

Dehydration, a very common complication of NVP, is also strongly linked to fatigue. It is critical for pregnant women to try their best to obtain adequate hydration/fluids and to avoid a cumulative effect of these symptoms. Nausea, vomiting, dehydration, and fatigue – combined – makes women feel markedly worse, and could potentially lead to depressive symptoms. Further, improved hydration can help increase blood pressure, appetite, and assist in blood volume expansion, thereby improving fatigue and potentially nausea as well.

Regarding rest, research has shown that the total amount of sleep women obtained the previous night is much more beneficial than daytime napping. However, women with evening/overnight nausea may find this very difficult to obtain (read Evening/Overnight Nausea).

Sensory Changes

Aversions to food and a change in smell perception can also contribute to waves of nausea and vomiting.

It’s been documented for more than 100 years that pregnant women have a heightened sense of smell – known as hyperosmia; however, recent research indicates this is more likely a heightened awareness of certain smells, rather than a “better” sense of smell than non-pregnant individuals (read more).

This hyperawareness appears to only include specific odors – usually intense, harmful ones. When women are already aware that cigarette smoke, coffee, garbage, and spoiled food are associated with harm during pregnancy, their odors may become “stronger".

Due to this awareness of very unpleasant odors, it is much easier for smells to trigger the gag reflex or a strong sense of disgust that can lead to near instant gagging/vomiting. At least two separate studies indicated that women who were adversely affected by odors early in pregnancy had more severe nausea and/or vomiting.

Taste may also be affected in women with severe NVP /HG that further inhibits a woman's ability to eat more nutritious items. A well-designed study reported that women affected by HG performed worst in taste identification when compared to healthy pregnant women or to healthy non-pregnant women.

Women with NVP tend to tolerate carbohydrates and sweeter foods easier than other types of foods. Interestingly, the same study above revealed that in women with HG, sweet foods were the best tolerated, and was the only food category rating similar to controls.

Further, fruity smells (lemon, banana and coconut) were tolerated well, and the consumption of fruits such as apples, watermelon, oranges, and bananas were the least likely to provoke nausea and/or vomiting.

Excessive saliva (ptyalism) can affect taste in early pregnancy, is common in women with NVP, and was previously strictly associated with women who suffered from HG. Women may have difficulty swallowing the excess and need to spit it out frequently, exacerbating NVP.

It is estimated that 60% of women with HG report excess salivation or ptyalism.

Excess saliva does not appear to be a direct result of pregnancy, but may be reported more often in women with NVP/HG due to an increase in vomiting, as vomiting itself causes an increase in saliva.

This symptom appears to decrease as NVP improves. Women can try to use gum, ice, or popsicles to improve bad taste and lessen gagging (read Management for more strategies).

Prevention Hypothesis

The prevention hypothesis, a popular theory first presented more than 40 years ago, indicates NVP is a protective mechanism and evolutionary trait. Nausea and/or vomiting, and its associated aversions (as described above), help pregnant women protect their embryo through the avoidance of foods that may contain chemicals/toxins.

Evidence of this hypothesis includes women's strong aversions to alcohol, coffee, meats, seafood, dairy, and raw vegetables – food groups most likely to carry harmful pathogens. The timing of NVP onset and relief also appeared to add further weight to this theory, as women tend to feel better toward the end of the first trimester, and the end of major organ development.

Women with NVP are also less likely to miscarry than women without symptoms; this also serves to corroborate this hypothesis.

However, this theory is also based on women’s immune systems being suppressed during early pregnancy, which research has revealed is not the case (read more). NVP was deemed necessary to avoid the ingestion of harmful toxins because women’s immune systems were weaker and could not fight off foodborne infection, which is no longer based on current evidence.

Researchers also have more data regarding the onset, peak, and resolution of NVP symptoms. The prevention hypothesis does not explain why most women have NVP far past the end of the organogenesis period. Further, NVP peaks around 9 to 10 weeks, which is past the 5 to 8-week time frame of major organ development.

There is also a significant nutritional cost with NVP, as women – especially with severe NVP – have a difficult time eating more nutritious foods (fruits, vegetables, dairy) when experiencing symptoms.

In addition, the avoidance of foods expected to hold higher risk of toxins, parasites, or chemicals is not true across all cultures; therefore, while aversions may be very important for toxin avoidance, culture may also play a role as to which foods are most perceived to be toxic.

Lastly, if NVP is an evolutionary trait, the biological mechanisms in which this trait results in actual symptoms are still not known, and even further, the trait is no longer applicable for fetal health in modern times.

Regardless, women need to eat through their symptoms (read more), and fortunately, brief periods of malnutrition do not appear to affect the embryo/fetus.

H. pylori

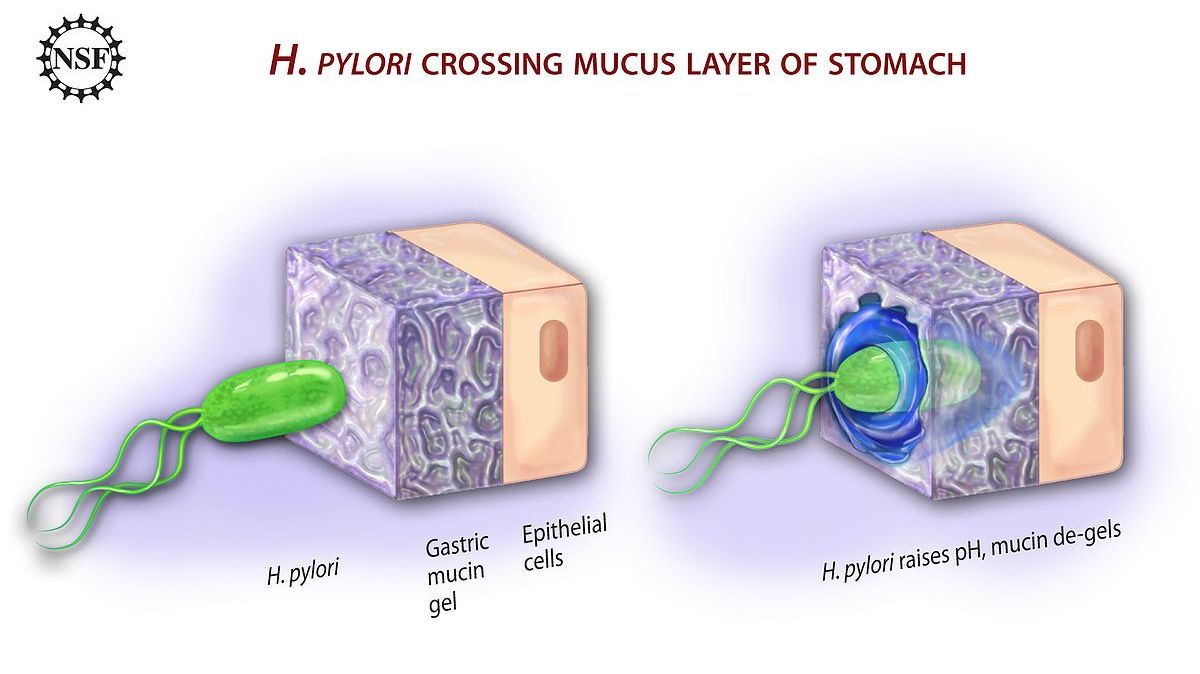

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a bacterium that produces multiple and serious gastrointestinal diseases and may play a role in HG.

H. pylori invades and infects the stomach lining, causing inflammation; it can persist for years based on its ability to adapt and survive in epithelial cells of the stomach. It does not always cause outward symptoms.

H. pylori infection affects approximately one-half of the world’s population. In studies in which data was available, H. pylori infection among pregnant women was estimated around 20% to 30% in Japan, Australia, and most European countries, and as high as 50% to 70% in Mexico and Texas in the United States.

H. pylori infection is most likely acquired before pregnancy; therefore, it is widely believed the hormonal and immunological changes during pregnancy may activate a latent (inactive) H. pylori infection.

Numerous studies have found an association between severe NVP, HG, and H. pylori infection. It is possible that H. pylori can affect the nerve and electrical functioning of the stomach (see GI section, above) making certain women more susceptible to extreme nausea/vomiting.

One study found that H. pylori had infected 89% of 45 women with severe NVP, but only 7% of those without NVP symptoms.

In contrast, several studies found no relationship between HG and H. pylori, and many women with H. pylori have no symptoms. These contradictory findings are likely from the lack of a universally accepted HG definition and that testing cannot distinguish between past or present infection or the type of strain, which causes different symptoms.

Therefore it is currently assessed that while H. pylori is likely not a sole cause of HG, it may be a contributing factor that HCPs should take into consideration in women with severe NVP and intractable cases of HG. This may be especially important since treatment options are lacking for women with HG, but H. pylori can be managed effectively.

There are several invasive and non-invasive methods used to diagnosis H. pylori infection. Noninvasive methods include serum antibody detection (blood work), carbon-labeled urea breath tests, and evaluating a stool (fecal) sample. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and biopsy of the stomach lining is considered the most invasive. H. pylori has also been detected in amniotic fluid after amniocentesis.

Treatment includes antibiotic therapy, which eradicates H. pylori in most individuals, along with NVP/HG symptoms. However, currently there are no guidelines for the evaluation or treatment of H. pylori during pregnancy as this has not been formerly or widely studied outside of small sample sizes and case studies. Therefore, the optimal treatment plan is unknown.

Specific treatment may consist of triple therapy, including a proton pump inhibitor, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin or metronidazole. Other studies have included penicillin and erythromycin.

While H. pylori is also associated with other complications during pregnancy to include iron deficiency anemia, fetal malformations, miscarriage, preeclampsia, reduced birth weight, and fetal growth restriction, some HCPs may advocate for treatment in the postpartum period:

Some researchers recommend that in women with H. pylori and NVP/HG, if symptoms can be managed to a tolerable degree with conventional methods, then ideally, treatment should begin after pregnancy and lactation have been completed. Further, specific antibodies against H. pylori may be transferred to the fetus/infant during pregnancy and lactation.

Thyroid Dysfunction

Thyroid dysfunction has been studied as a possible mechanism for NVP and HG.

Pregnancy requires an increase in thyroid hormone, and it is estimated 2% to 15% of all pregnant women have either hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism. Abnormal results on thyroid function have been found in more than two-thirds of women with HG, yet, thyroid screening is not routine in the evaluation of NVP .

Hyperthyroidism: excess in thyroid hormone; likely due to cross reactivity between Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH) and HCG resulting in overstimulation; most commonly found in women with Graves’ disease; can increase the risk of pregnancy complications if left untreated.

Hypothyroidism: deficiency of thyroid hormone; may result in no symptoms – but symptoms of more overt hypothyroidism include fatigue, cold intolerance, weight gain, constipation, and dry skin; can cause problems during pregnancy if left untreated.

However, even when thyroid problems are identified and treated, some studies have found that treatment does not appear to relieve NVP symptoms in all cases. Further, some women with HG may have normal TSH levels by 20 weeks of pregnancy without any intervention.

Regardless, thyroid function screening is a simple blood test, and researchers advocate for this screening at the first prenatal appointment, as even transient or borderline dysfunction could cause additional complications in some women, unrelated to NVP (read Iodine and Fetal Brain).

Placenta

It is believed the placenta may play a significant role in activating the brain’s vomiting center and lowering the threshold necessary to induce vomiting.

Evidence for this includes the observation that pregnancies with no fetus (complete hydatidiform mole) but placenta are associated with severe NVP indicating the placenta may play an obvious role.

Further, some studies have found an association between HG and placental disorders to include preeclampsia and placental abruption, as well as a large placenta size, although not all studies report these findings.

Lastly, women with severe NVP or symptoms that last the entirety of pregnancy generally experience complete relief almost immediately after delivery (most likely due to delivery of the placenta). This is also very similar to the resolution of preeclampsia. In contrast, hormones may take several weeks to return to normal levels.

According to a study published in December 2017, the peptide hormone endokinin could be responsible for NVP . Placental endokinin is a key factor for ensuring successful implantation of the placenta; therefore, endokinin levels rise during pregnancy to ensure good placental blood flow. These levels of endokinin can also activate the vomiting center of the brain, adding weight to the strong association between NVP and a healthy pregnancy.

Of note, the study emphasized that smoking during early pregnancy can disrupt this process, by releasing lung endokinin into the blood stream, exacerbating nausea and interfering with placental endokinin.

As of July 2020, no follow-up studies have been identified regarding endokinin and NVP.

Action

Pregnant women who are experiencing NVP symptoms should learn as much as possible about the condition, to include possible complications as well as management methods based on the possible causes/contributing factors to their symptoms.

Women should call their HCP as soon as they begin to feel symptoms. It is important that women get assessed for these possible contributing factors prior to symptoms becoming too much to handle (i.e. get in front of it). If women only ask their HCP for help once their symptoms are severe, nausea/vomiting can be much harder to manage (read Complications).

Women should also be assessed/screened for the following:

Acid reflux

Constipation

History of migraines, motion sickness, oral contraceptive use, and NVP

Family history of NVP

Underlying gastrointestinal disorders

Multiple fetuses

Fatigue and exhaustion

Nausea/vomiting triggers

Intensity of aversions

Stress/anxiety related to family, relationships, employment

Depressive symptoms

Women should consider sharing their NVP experience (below), especially how they felt, how long it lasted, what may have caused or contributed to their symptoms, and anything they did that relieved symptoms, even if only temporarily.

This can be a very difficult few weeks/months for women. Reading experiences of other women can help them better mentally cope and manage their symptoms and teach them to be a better advocate for themselves at home, at work, and at their HCP's office.

Partners/Support

It is critical that the partners, family members, and friends who support pregnant women learn more about NVP and correct falsehoods associated with this condition. As indicated above, NVP is neither simple nor straightforward. It is also not easily managed or treated, and in many cases, does not go away quickly.

Partners/support also need to be patient. If researchers cannot determine a possible cause or most optimal management strategy to relieve symptoms after decades of study, partners/support should not expect pregnant women to either. It takes time and women need help.

Pregnant women should be given adequate and positive emotional support, help with their symptoms, and above all – recognition and understanding that what they are going through is not only real, but recognized by their family members.

Partners should also read:

Resources

Nausea and Vomiting of Pregnancy (Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2011 Jun)

Nausea and Vomiting of Pregnancy-What’s New? (Auton Neurosci. 2017 Jan)

Morning Sickness: Nausea and Vomiting of Pregnancy (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists)

Nausea and Vomiting of Pregnancy: Committee Opinion 189; January 2018 (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists)