Pushing

Pushing occurs during the second stage of labor, which is full dilation to delivery. The length of time it can take women to push during this stage is affected by numerous variables. Some women may only need a couple pushes, while other women may need 2 to 3 hours.

The urge to push is normally greatest during the transition phase of the first stage of labor (between 7 and 10 centimeters). Women are often told to avoid pushing prior to full dilation. Although there are very few studies regarding cervical trauma or complications to the baby if this occurs, the main complication is the woman’s exhaustion level, as the baby cannot pass through a cervix that is not fully dilated.

Evidence-based research regarding the best pushing positions are inconsistent and often controversial; there is no single position that has been shown to work best for all women, shorten the duration of labor, or cause the last amount of perineal tearing or trauma. It is therefore recommended that women should be encouraged to choose positions that make them the most comfortable.

Delayed pushing, in which women delay pushing until they feel the natural urge to do so, has been linked to shorter pushing time overall; whether this delay results in an overall lengthier second stage of labor is unclear.

Regardless of inconsistent evidence, women have options regarding when they would like to push, how they want to push, and the position in which they would prefer to push, as long as there is no maternal or fetal distress.

Background

Bearing down (pushing) during labor is usually instinctive and spontaneous, but women may require assistance and coaching from HCPs and/or their support system.

There are three major categories of pushing:

Spontaneous bearing down: women push during contractions as soon as they can no longer resist the urge

Self-directed pushing: women still push when they feel the urge, but this version requires assistance from HCPs to include getting her to focus, change positions, breathe deeply, and tell her when a contraction is coming (especially if epidural was used)

Directed pushing: the only method used by almost every hospital until the late 1980s; at the beginning of every contraction, the mother holds her breath, bears down, and counts to 10; this method has very little evidence to support its continued routine use.

However, a combination of techniques may also be useful depending on different situations, the mother’s exhaustion level, use of pain medication, and the baby’s overall tolerance of labor/contractions.

Pushing is the most stressful part of labor for the baby; shortening this phase is a traditional part of the “active management of labor”:

The goal of active management is to prevent prolonged labor, which involve HCPs potentially intervening with various methods or techniques (Augmentation Methods). Prolonged labor could lead to complications for the mother, baby, or both; it could also lead to cesarean section.

An HCP can decide at any point during the pushing stage that a cesarean delivery is necessary, usually because either the mother, baby, or both are in some type of distress and the baby needs to be delivered immediately.

Timing

Pushing occurs during the second stage of labor (full dilation to delivery). The length of time “pushing” can take is affected by:

The mother’s pushing position and efforts

The position of the fetus

Station

Contractions (and pattern)

Epidural use

Pain medications

Position describes the relationship of the presenting part (usually the head) to woman’s pelvis:

Anterior position: the back of the baby’s head points toward the woman’s front (most ideal for delivery)

Transverse: the back of the baby’s head points toward the woman’s side

Posterior: the back of the baby’s head points toward the woman’s back (also known as “sunny side up” and can cause back labor)

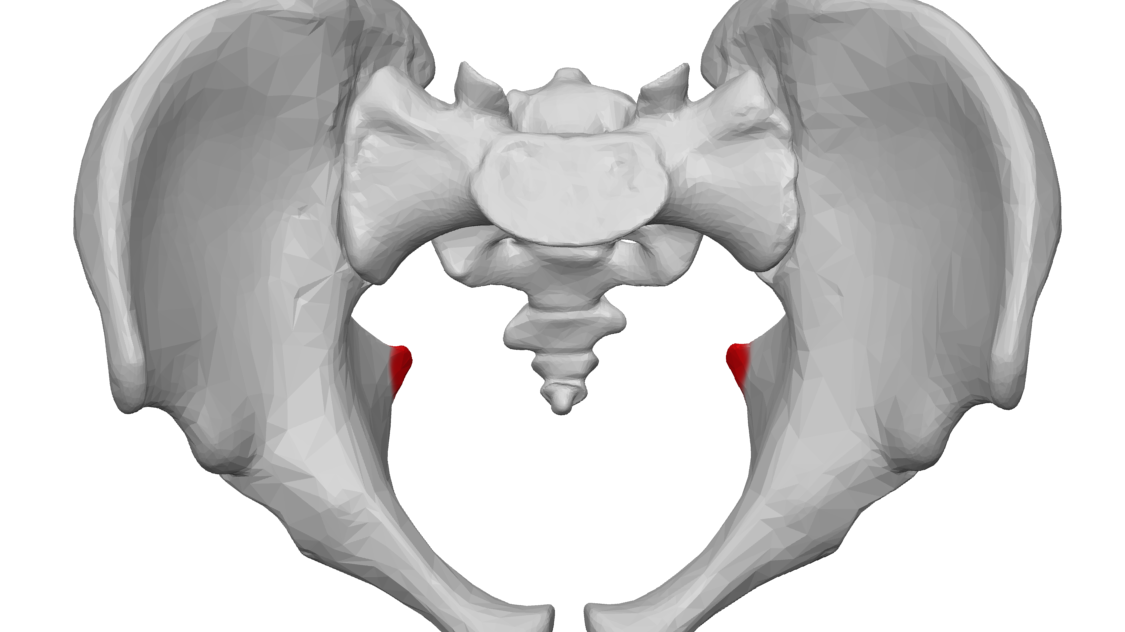

Station: expressed in centimeters above or below the level of the maternal ischial spines (image below); level with the ischial spines corresponds to 0 station; levels above (+) or below (−) the spines are recorded in centimeter increments.

Lie describes the relationship of the long axis of the fetus to that of the mother (longitudinal, oblique, transverse).

Presentation describes the part of the fetus at the cervical opening (usually the head but may also be the shoulders or another part that constitutes a breech presentation).

On average, the pushing phase can last 50 minutes to 2 to 3 hours in women who have never delivered before, and about 20 to 60 minutes in women who have previously delivered. In a woman who has had multiple vaginal deliveries, it is possible that only two or three pushes are necessary.

It is recommended that as long as fetal signs are reassuring and there are no signs of physical obstruction, HCPs should not set a time limit for this stage.

This image contains triggers for: Real Delivery

You control trigger warnings in your account settings.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' (ACOG) recommendation for duration of pushing for a woman’s first delivery is 3 hours plus an extra hour if an epidural was used; the recommendation for women who have had a prior delivery is 2 hours, plus an extra hour if an epidural was used.

The goal of the above recommendation is to give women enough time to push prior to making a diagnosis of “prolonged labor” and to prevent cesarean section if possible.

Delayed Pushing

Traditionally, women have been advised to push with each contraction as soon as the woman was determined to be fully dilated. However, current evidence indicates women should not be forced to push until they feel an urge to do so.

Delayed pushing, which may mean a “break” of 60 to 90 minutes after complete cervical dilation, has been linked to shorter pushing time overall; whether this delay results in an overall lengthier second stage of labor is unclear.

For example, if a woman began pushing prior to feeling a natural urge to push, it could take her two hours to push and complete delivery. However, if she waited an hour, or until she felt she needed to push, she may only require one hour to delivery. Although both outcomes resulted in the same amount of total time (2 hours), the woman only needed to push for one hour.

However, it is possible this method could result in a significantly longer time to delivery, but it is more likely this will also provide the woman a much better birthing experience.

In otherwise healthy labors, with reassuring fetal signs of wellbeing, fully dilated women should be able to rest and allow for further fetal descent if they wish; this may prevent women from getting too fatigued prior to complete delivery. Delayed pushing has also been linked to fewer fetal heart decelerations and less fetal desaturation, especially since “aggressive” coaching techniques may be the cause of non-reassuring fetal heart rate patterns.

It is also possible, that if the baby does not respond well to pushing, women can stop and rest for several contractions – which could allow the baby to recover. If the baby still responds poorly, pushing every other contraction may also be attempted.

However, ACOG recommends that women who had an epidural should begin pushing immediately upon full dilation to avoid complications such as possible infection or hemorrhage.

Women should discuss with their HCP the risks and benefits of delayed pushing, specifically to their own pregnancy.

Pushing Position

Evidence-based research regarding the best pushing positions are inconsistent and often controversial; there is no single position that has been shown to work best for all women, shorten the duration of labor, or cause the last amount of perineal tearing or trauma. It is therefore recommended that women should be encouraged to choose positions that make them the most comfortable and gives them full ability to push most effectively.

For example, an upright position may be more effective than a woman pushing while lying on her back, but this recumbent position does make it easier to monitor contractions and fetal heart rate, as well as to perform vaginal examinations and augmentation methods. Further, evidence is inconsistent regarding a sitting position and degree of perineal trauma.

This image contains triggers for: Real Delivery

You control trigger warnings in your account settings.

However, if a woman is considered low-risk, and does not require constant monitoring or intervention, a recumbent position may not be advised. This position is linked to maternal abdominal blood vessel compression which can lead to less effective contractions, less perineal muscle relaxation, higher rates of pain medication use, and/or longer labor length.

It is currently assessed the “on all fours” position may lessen the gravitational effect as well as the peak and duration of contractions, may lessen pelvic pain, allowing a woman to receive lower back massage, and may assist in the baby’s internal rotation.

A study published in May 2021 that utilized magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) found that pelvic capacity increases as pregnancy progresses. Further, the results also indicated that the supine position is optimal for increasing pelvic inlet size, while the semi-lithotomy (flat on back, legs up) and kneeling squat positions are optimal for increasing mid- and outlet-pelvic capacities.

A squatting position utilizes the assistance of gravity, opens the pelvis, and may be a better position for both the strengthening and relaxation of the perineal muscles.

Counting to 10 (Directed Pushing)

The traditional way of assisting women during second stage labor typically involves pushing immediately at 10 cm regardless of whether the woman has an urge to push. This is followed by instructions telling the woman to take a deep breath and hold it (closed-glottis pushing) while an HCP counts to 10. However, this type of pushing is not beneficial and likely does not shorten this stage of labor.

During delivery, this mode of pushing can lead to various changes in both the maternal and fetal circulation and can, overall, decrease blood flow to the uterus. It is advised that women should avoid holding their breath during delivery, and instead perform slow exhales (open-glottis pushing).

When the time is right for pushing, the best approach based on current evidence is to encourage the woman to do whatever comes naturally; for example, bearing down and holding it as long as she can, rather than insisting that she hold her breath and push to the count of 10.

Further, forcing/holding a woman’s legs back against her abdomen can overstretch the perineum and may lead to tearing.

Additionally, three to four good pushing efforts of 6 to 8 seconds in length per contraction is considered an effective amount of time and strength to progress delivery.

Crowning to Delivery

The urge to push is normally greatest during the transition phase of the first stage of labor (between 7 and 10 centimeters). Women are often told to avoid pushing prior to full dilation. Although there are very few studies regarding cervical trauma or complications to the baby if this occurs, the main complication is the woman’s exhaustion level, as the baby cannot pass through a cervix that is not fully dilated.

Once full dilation occurs, and the woman has pushed enough to where the baby’s head moves closer through the vagina, the woman will experience an increased feeling of pressure on her rectum. This can lead to some women “pooping” during labor which occurs very frequently and is considered normal, as well as a good sign:

When pushing, women are often told by HCPs to bear down as if they were having a bowel movement; this is because both actions use the same muscles.

During labor, the central portion of the perineum is transformed from a wedge-shaped, 5 cm thick tissue mass to a thin structure less than 1 cm thick, due to the pressure of the fetal head. This causes the anus to open about 2 to 3 cm.

Additionally, stool that has formed in the large intestine prior to labor/delivery often moves downward because of this pressure; this stool (usually a small amount) is then expelled through the already slightly opened anus during pushing/delivery.

It has been formally documented since at least 1887 that having a bowel movement is a normal and often seen part of the delivery process. HCPs have seen this occur hundreds of times and they know women are concerned about it. It is taken care of very quickly and discreetly, and women may not even know it occurred due to the intense feeling of pressure that can numb the area.

As the baby’s head can be seen through the vaginal opening, it gradually stretches the vaginal and perineal tissues. With each contraction, the opening is dilated by the fetal head to gradually form an ovoid shape and finally an almost circular opening. When the largest head diameter is at the vaginal opening, this is known as crowning and it is commonly referred to as the “ring of fire” (as stated above, some women may be numb, and not experience this feeling).

The woman should avoid pushing too hard or too fast at this time and listen to her HCP in order to avoid tearing or the baby coming out to quickly.

As the baby is only several contractions away from delivery at this point, contractions may now last a full 60 seconds, and recur at an interval no longer than 90 seconds.

Traditionally, the HCP would make an incision from the vaginal opening to about midway through the perineum. It was thought this type of controlled incision, known as an episiotomy, would prevent the mother from a more severe uncontrolled tear. However, there is no evidence to support the routine use of episiotomies, especially for the prevention of tearing (read Tearing and Episiotomy).

As the baby’s head is delivered, the HCP will check to see if the umbilical cord is around the neck and remove it if necessary; even when the cord is around the neck, this is usually not a concern in most deliveries.

Once the head is out, it usually only takes one more push to deliver the rest of the baby. Most often, the shoulders appear at the vulva just after external rotation and are born easily. The HCP will then grasp the sides of the head and use gentle downward traction then an upward movement to assist delivery of the second shoulder; the rest of the body generally follows the shoulders.

Action

Regardless of inconsistent evidence, women have options regarding when they would like to push, how they want to push, and the position in which they would prefer to push, as long as there is no maternal or fetal distress.

Women should attempt to find an HCP that shares their views regarding pushing, and will allow them the necessary time to push as they wish, as long as the HCP has deemed it safe to continue these methods.

Women should refer all questions and concerns they have regarding the second stage of labor to their HCP. Women should also consider using a midwife or hiring a doula, who can help remind women of various positions and pushing techniques throughout labor. Labor and delivery nurses are also very helpful in this regard, and are usually present with women for the entirety of the pushing stage (read Types of Healthcare Providers).

Partners/Support

Partners and those who will be supporting the woman in the delivery room can be of great assistance during the pushing stage. From holding her legs (not too far back) and offering words of encouragement, the emotional support partners can provide cannot be overstated.

Pushing is hard work; some women may push between one and three hours; support is necessary to remind her to keep going, take breaks, and not to give up. Support members can remind her of her earlier wishes (birth plan), but keeping in mind that women often do not know what they will want or prefer until they are in pain, and they should be provided some flexibility without judgment.

Resources

Approaches to Limit Intervention During Labor and Birth (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists)