Molar Pregnancy

Molar pregnancies, when abnormal trophoblastic tissue grows into the uterus, are part of a category of conditions known as Gestational Trophoblast Disease (GTD) and are considered very rare. An obstetrician may only see one case of molar pregnancy every other year.

Molar pregnancies are not viable pregnancies, and are managed surgically. An additional smaller percentage of women may have severe invasion of the uterus, which can require further treatment, such as chemotherapy, as some forms can be malignant.

However, cancerous forms of GTD have an estimated cure rate up to 100%, and up to 98% of women with molar pregnancies go on to have successful pregnancies in the future.

The most common symptoms of molar pregnancy includes bleeding, severe vomiting, and a larger uterine size in comparison to gestational age. Women should always call their HCP for bleeding during early pregnancy to help rule out ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, and molar pregnancy.

Background

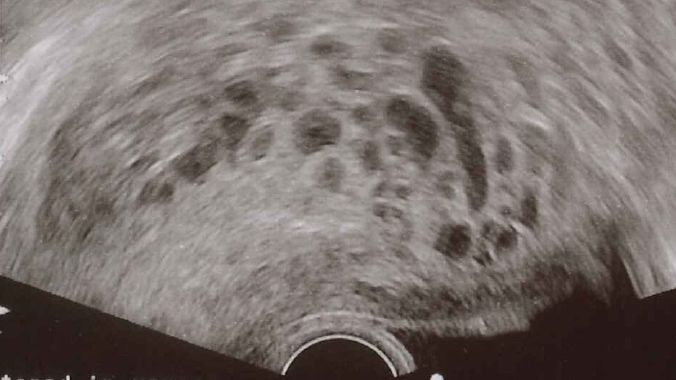

Note: An internal/anatomical photograph of a molar pregnancy is pictured below.

Molar pregnancies are part of a category of conditions called Gestational trophoblast disease (GTD), a group and range of conditions that causes tumors to grow in the uterus after pregnancy has occurred. These tumors grow from the trophoblast cells that develop into the placenta.

The different types of GTDs are categorized by how aggressively they invade the uterus and the likelihood they will metastasize (spread). The main types of GTD are:

Hydatidiform mole (complete or partial) – the most common form (usually benign)

Invasive mole

Choriocarcinoma

Placental site trophoblastic tumor

Epithelioid trophoblastic tumor

The malignant forms of GTD, which include invasive mole, choriocarcinoma, and placental and epithelioid trophoblastic tumors, are more specifically termed gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN). GTN can develop weeks to years after any type of pregnancy, but tend to occur most often after hydatidiform mole.

Hydatidiform mole is the most common form of GTD, and is also known as a molar pregnancy. There are two types of molar pregnancies, complete molar pregnancy and partial molar pregnancy, which, in most cases, are benign (noncancerous).

A complete mole most often develops when 1 or 2 sperm cells fertilize an egg cell that contains no nucleus or DNA (the mother’s DNA is lost). As such, all the genetic material comes from the father, so no fetal tissue develops, just fluid-filled cysts.

The photo below depicts internal image of a complete hydatidiform mole after a hysterectomy.

This image contains triggers for: Blood, Internal Anatomy, Procedure, Surgery

You control trigger warnings in your account settings.

In a partial molar pregnancy, two sperm fertilize an egg, but the mother’s DNA is also present; therefore, there are 69 chromosomes in the abnormally fertilized egg, instead of 46. Some fetal tissue may begin to grow, but it does not survive, and stops growing early in pregnancy.

Molar pregnancies are rare, occurring in about 0.1% of pregnancies in the United States, England, and Wales. In developing countries, the prevalence is slightly higher, around 2% to 3%. It is estimated that an obstetrician may see only one new case of molar pregnancy every other year.

Most partial moles are diagnosed as miscarriages that were later determined to be molar pregnancies based on examination of the tissue. Other molar pregnancies are found during a first ultrasound examination, around 6 to 10 weeks of pregnancy.

Signs and Symptoms

Women with molar pregnancies generally feel the same early pregnancy symptoms as women with viable pregnancies, but severe vomiting is usually present, and the uterus is larger than should be for gestational age. Passage of grape-like tissue is also a hallmark of molar pregnancy, especially later in gestation.

Light to severe bleeding may also be present, as a mole that grows completely through the wall of the uterus might result in bleeding into the abdominal or pelvic cavity, which is life-threatening.

Other signs/symptoms of a molar pregnancy include:

High blood pressure

Overactive thyroid

Bleeding (prune juice appearance/dark brown)

Women with a complete mole may have very high levels of human chorionic gonadtropin (HCG), typically greater than 100,000, whereas partial moles may be within the normal range for gestational age or even lower, presenting similarly to a threatened miscarriage. Higher levels of HCG are more concerning, as more persistent, complete molar pregnancies have this trait.

Risk Factors

The biggest risk factor for molar pregnancy appears to be age; women at the lower and higher ends of reproductive age – between 13 and 18 years of age and those 45 to 50 years of age – appear to be most at risk. Other risk factors include a prior molar pregnancy or having two or more miscarriages.

Interestingly, the risk of subsequent molar pregnancy is not decreased by changing partners, which indicates risk factors may not be due to the physical properties of sperm (despite the role of sperm in its formation).

Diagnosis and Management

As a molar pregnancy is not a viable pregnancy, all tissue needs to be removed, as complications include a potentially serious form of cancer. Ultrasound examinations and blood work are required to confirm diagnosis, as well as a chest x-ray to determine if the invasion has spread to the lungs.

The most common management of molar pregnancy is dilation and curettage (D&C) to remove the inner lining of the uterus which removes all molar tissue. However, this procedure will not work for molar pregnancies that have grown deeper into the uterus.

After a D&C, the HCP will regularly monitor HCG levels to make sure they return to normal (up to one year), which confirms all tissue has been removed. If any tissue remains, more treatment is required.

About 20% of women will have persistent molar tissue (persistent GTD/GTN), which is more common with a complete mole. Although this tissue can still be benign, it could also be choriocarcinoma, a cancerous form of GTD (with an almost 100% cure rate).

Treatment at this stage includes methotrexate, which stops rapidly dividing cells from growing. Methotrexate is also used to treat some forms of cancer as well as ectopic pregnancy. Other forms of treatment may also be needed depending on severity of invasion, to include a possible hysterectomy (removal of uterus).

A choriocarcinoma can also spread to other parts of the body such as the lungs, liver, and/or brain. Fortunately, even in advanced cases, prognosis is excellent, and a complete cure is considered standard.

Future Pregnancies

Women with a prior molar pregnancy often go on to achieve a healthy full-term pregnancy in the future (up to 98%). However, based on strict HCG follow up for any possible amount of retained molar tissue, women may be asked by their HCP to wait 6 to 12 months before trying to conceive. Women who undergo chemotherapy are advised to wait at least one year after completing treatment.

Action

The most common symptoms of molar pregnancy includes bleeding, severe vomiting, and a larger uterine size in comparison to gestational age. Women should always call their HCP for bleeding during early pregnancy to help rule out ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, and molar pregnancy.

Resources

Management of Molar Pregnancy (Journal of Prenatal Medicine)

The Management of Gestational Trophoblastic Disease (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists)