Group B Strep

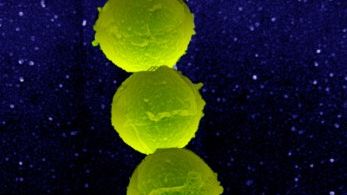

Group B streptococcus (GBS) is a type of bacteria present in the digestive, urinary, and reproductive tracts of both men and women, and is usually harmless (with no symptoms).

However, during pregnancy, GBS can be passed to the newborn during vaginal delivery and can cause a severe infection that presents anywhere from 24 hours to 3 months after delivery. If caught early, the baby can be completely cured with antibiotics, but delayed diagnosis can result in very severe illness.

To avoid these complications, most international organizations recommend universal screening of pregnant women for this bacterium between 35 and 37 weeks of pregnancy. Women who test positive will receive intravenous antibiotics during labor to prevent the transfer of possible infection to the newborn.

Women should continue reading to learn more about why these guidelines are in place, when they are screened, their treatment options, and possible risks to the newborn.

Background

Group B streptococcus (Group B strep/GBS) is a common bacterium often carried in the digestive, urinary, and reproductive tracts of men and women, and is usually harmless in adults but can cause serious illness in newborns.

It is estimated that 1 in every 4 pregnant women carries GBS in their body; it does not cause symptoms, although some women may develop a urinary tract infection (UTI).

GBS is not a sexually transmitted infection and requires no treatment unless an outward infection develops. GBS is similar, but different from, Group A streptococcus – which causes strep throat.

GBS has been known to be fatal in humans since 1938 and was first identified to cause infection during pregnancy in the 1960s. By the 1970s, GBS infection was a leading cause of neonatal death in the United States (U.S).

In the early 1990s, there were approximately 1.7 cases of early-onset GBS infections per 1,000 live births. Current estimates reveal this has decreased to 0.34 to 0.37 per 1,000 live births in recent years due to the introduction of antibiotics during labor.

Pregnancy – Overview

Although usually harmless in non-pregnant women, GBS can cause certain complications during pregnancy, such as:

Infection of the placenta and amniotic fluid (chorioamnionitis)

Inflammation and infection of the uterine lining

Infection of the bloodstream (sepsis)

The biggest complication of GBS is the passage of the infection to the newborn. GBS spreads to the newborn during vaginal delivery as the baby comes into contact with the bacterium. A woman with treated GBS has a 1 in 4,000 chance of passing the infection to her baby; with untreated GBS, this rises significantly to 1 in 200. These odds are even higher if:

The baby was born prematurely

Membranes ruptured (“water broke”) 18 hours or more prior to delivery

The woman had a fever during labor

The woman had a prior baby with a GBS infection

The woman had a UTI during pregnancy, caused by GBS

Newborn Risks

While most newborns born to mothers with GBS are healthy, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC):

About 900 babies get early-onset GBS disease every year

About 1,200 babies get late-onset GBS disease every year

2 to 3 in every 50 babies (4% to 6%) who develop GBS disease will die

GBS infection can lead to life-threatening complications in newborns and infants, including fever, lethargy, pneumonia, meningitis, and bloodstream infection (early onset).

Early-onset infections occur during the first week of life, generally within the first 24 to 48 hours after birth. Symptoms of early onset infection occur due to respiratory failure which develops into a bloodstream infection (bacteremia), leading to septic shock.

About 30% of all early onset cases are in preterm infants; preterm infants with early-onset GBS infection have a fatality rate between 20% to 30% compared to 2% to 3% in term infants.

Early-onset infection, and its potential consequences to the infant, have a significant impact on parents. A study published in November 2021 explored (27) parents' first-hand lived experience of having an infant with early onset group B streptococcus. Participants documented their experiences in their own way, reporting their thoughts and feelings, experiences, and events that were meaningful to them. Participants experienced a wide range of emotions to include grief, sadness, and guilt, as well as frustration at information they were receiving from HCPs. Their experiences also had implications for the planning of future pregnancies.

Late-onset infections develop between 1 to 12 weeks after delivery (can sometimes occur even later) and can lead to meningitis and/or pneumonia. Women should seek emergency care for their baby if they notice any of these signs and symptoms of late-onset infection:

Difficulty breathing and feeding

Fever

Lethargy

Irritability

Vomiting

Slow breathing/heart rate

Diagnosis of a baby with GBS includes tests of the blood and spinal fluid, as well as a chest x-ray to assess for respiratory failure and pneumonia; treatment includes the antibiotics penicillin or ampicillin.

Maternal Screening Test

It is recommended that all pregnant women receive a swab screening test between 35 and 37 weeks of pregnancy. The test involves the HCP using a clean swap to collect a sample from around, not in, the vagina and anus. Patients at risk for preterm delivery will often receive the screening test prior to 35 weeks.

The test is performed later in pregnancy because a woman can be positive or negative at different times; however, the most important time is GBS status near term. A positive test indicates that a woman is carrying GBS and can possibly pass the infection to her newborn.

Unfortunately, the screening test does not catch all cases of GBS infection. Approximately 60% of cases of early-onset GBS infection occur in neonates born to women with negative GBS culture at 35 to 37 weeks. It is unclear if conducting this screening between 38 and 39 weeks would be of higher benefit, as many women may deliver before this time.

Management

Women who test positive for GBS are given intravenous (IV) antibiotics (penicillin, or an alternative) during labor to prevent the passage of infection; IV antibiotics work within a matter of hours. Antibiotic pills cannot be taken at the time of diagnosis because the bacteria can return before labor. Most babies born to women who tested positive for GBS bacteria do not need treatment if their mother received antibiotics during labor.

Since the implementation of universal screening for GBS and preventative antibiotic use, the incidence of early-onset GBS infection has decreased approximately 80%.

Due to the high risk of preterm infants contracting early-onset GBS, women who go into labor prior to 37 weeks and have not taken the screening test will likely receive IV antibiotics during labor, as will a woman who tested positive in a prior pregnancy – no matter her current status.

However, prophylactic IV antibiotics remains controversial on whether exposing the mother to potentially unnecessary antibiotics is outweighed by the potential benefits. It is also debated on whether IV antibiotics have any effect on late-onset infection. Women should have a risks and benefits discussion with their HCP.

Women who are having a planned cesarean section do not need antibiotics if labor has not yet begun on its own and the fetal membranes are still intact.

Although it's not available yet, human trials are currently underway for a GBS vaccine. Until a vaccine becomes available, the best way to prevent complications is for women to get screened in the third trimester.

Action

Women should follow the screening recommendations of their HCP. HCPs are aware some women are not very comfortable with this type of screening for the first time. The swabbing is very quick, painless, and does not go inside the rectum.

Women should know, and inform their HCP of, their medical history; women should also understand their risk factors.

If screening is positive, each woman needs to have a risks and benefits discussion of treatment with their HCP.

Women should also consider sharing their experience regarding screening or testing positive for GBS and if they received antibiotics. This can help women learn from other women with a GBS positive screening and help them feel less anxiety near term.

Resources

Prevention of Group B Streptococcal Early-Onset Disease in Newborns (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists)

Group B Strep (FAQ) (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists)

Group B Strep (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

Group B Streptococcus (GBS) in pregnancy and newborn babies (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists)

Group B Strep International (Non-profit)