Vagina

Like the cervix, the vagina undergoes remodeling of its tissues to support stretching of its walls during delivery and a return to normal in the postpartum period (as much as possible).

In addition, although the most well-known changes to the vagina occur after delivery, the vagina also experiences an increase in discharge, swelling, and risk of infection during pregnancy.

Women should become familiar with vaginal anatomy, pregnancy-related changes to the vagina, and potential signs of infection. If women observe or experience anything unusual regarding their vaginal health during pregnancy, they should call their HCP.

Background

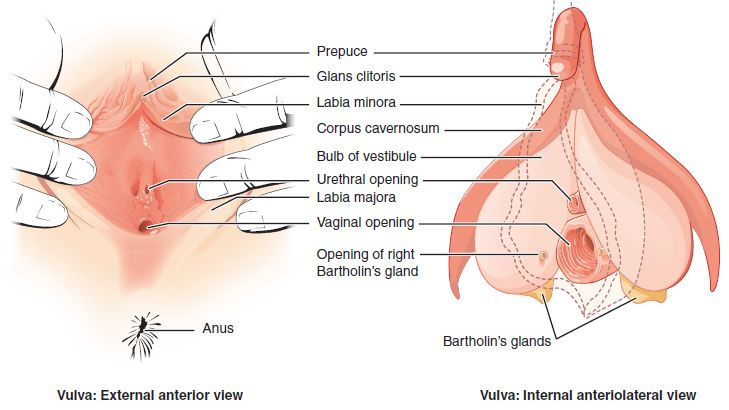

Vaginal anatomy:

The external female genital area is called the vulva

Labia majora are the outer folds

Labia minora are the inner folds

The clitoris is located at the top of the labia minora and extends deep inside the body

The perineum is the area between the anus and the vagina

The vagina is an opening that extends from the exterior part of the vulva to about 7 to 10 cm internally to the cervix

Vaginal changes during pregnancy are common. These symptoms can include vulvar burning and pain, pain with sex, discharge, skin color changes, swelling, itchiness, infection, and urinary problems. Most symptoms either go away completely after delivery or decrease gradually over a span of a few weeks (Note: Delivery also brings its own set of vaginal-related symptoms).

Infection

Microbiome is the state of trillions of bacteria, fungi, and viruses within the body, and each person’s is unique. Vaginal infections can occur if anything disrupts the natural balance of the bacteria normally present in the vagina; pregnancy causes a less-diverse shift to this microbiome.

In general, there is no real "normal" vaginal microbiome, as women of different races have a unique vaginal microflora and these can even change by region. Further, the vaginal microflora is constantly in flux; it's affected by gestational status, menstrual cycle, sexual activity, age, and contraceptive use.

Despite these differences, it is currently assessed that during pregnancy, the vaginal bacteria community is typically only dominated by one or two species of Lactobacillus, a type of bacteria normally found in much larger numbers in the vagina to help keep it acidic. This can increase the risk of lower genital tract infection.

Further, the vagina experiences increased blood flow during pregnancy, which can increase internal temperature. Coupled with a change in microbiome, this can raise the risk of infection further.

Additionally, high levels of reproductive hormones provide a higher glycogen content in the vaginal tissue, which is an excellent source for bacteria and fungi to survive.

The vaginal microbiome may play a role in adverse birth outcomes:

Vaginal infections (or bacteria in the microbiome) during pregnancy can cause premature birth, intra-amniotic infection, premature rupture of membranes, low birth weight, miscarriage, chorioamnionitis, postpartum endometritis, inflammatory pelvic disease, and possible illness of the newborn if not diagnosed early and treated properly. Early treatment of infections can help prevent possible transmission to the fetus.

A study published in November 2021 evaluated associations between groups of maternal infections and birth defects among 3096 cases and 7446 controls that were registered in the Congenital Defects Surveillance Programs of two Colombian cities between 2001 and 2018. The most common single infection between cases and controls was vaginal infection.

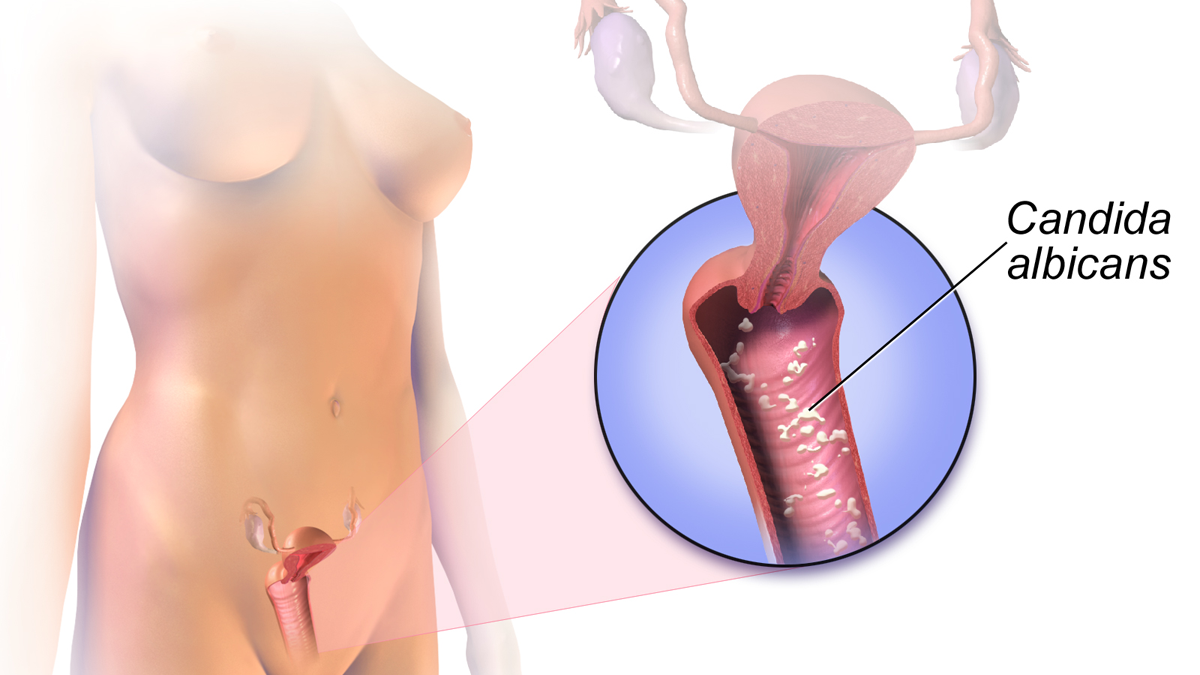

In general, the most common vaginal infection is thrush (vulvovaginal candidiasis/yeast infection), an overproduction or overgrowth of yeast in the vagina, and it occurs more often in pregnancy.

This infection is easily treated with oral medication or a vaginal suppository. Symptoms of thrush include itching and irritation along with white, “cottage cheese” type discharge that may or may not have an odor.

Topic azole antifungals are considered the medications of choice during pregnancy, due to their positive safety profiles.

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is caused by an overgrowth of the bacteria that normally live in the vagina (as oppose to fungal, above). Symptoms of BV include increased milky, foul-smelling (“fishy”) discharge. Some women may also be asymptomatic.

Fertility: BV adversely affects the vaginal microbiome, which plays an important role during embryo implantation. BV is more common in women struggling with infertility and is associated with reduced rates of conception.

During pregnancy, BV treatment is critical as BV increases the risk of contracting sexually transmitted diseases, including gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis, trichomoniasis, HIV, and HPV. It also increases the risk of sepsis, miscarriage, preterm premature rupture of membranes, preterm labor, and intra-amniotic infection.

BV is also associated with inflammation of the vagina, which can progress to inflammation of all fetal membranes, which then leads to premature rupture of membranes or preterm delivery.

However, treatment of BV does not always treat the more systemic inflammatory response, or lower the risk of subsequent preterm delivery; therefore, prevention and early management is most optimal.

BV is a bacterial infection, and is therefore treated with antibiotics, either orally (through the mouth) or suppository (inserted into the vagina).

Although not technically a vaginal infection, a urinary tract infection (UTI) can occur due to the presence of bacteria in the urine or genital area (bacteriuria); UTIs are more common during pregnancy.

Most UTIs start in the lower urinary tract, which is made up of the urethra and bladder. Bacteria live on the skin near the anus or in the vagina, which can spread and enter the urinary tract through the urethra, causing a UTI.

If bacteria move farther up the urethra and the infection is left untreated, this can cause a bladder or kidney infection that could produce severe complications during pregnancy (read more).

Discharge

Vaginal discharge increases during pregnancy to keep the vagina clean and fight off potential infection. This may be in direct correlation to the increased risk of infection during pregnancy.

Increased discharge (due to progesterone) keeps the genital area clean by removing dead cells from the vaginal lining, thereby keeping the uterus free from pathogens that could cause infection. Discharge may be heaviest in the second and third trimesters and may be confused with urine leakage or rupture of membranes.

The mucus from the mucus plug is also responsible. This mucus (again, due to progesterone) continues to flow into and out of the vagina throughout pregnancy so the plug always contains "fresh" mucus to keep pathogens out of the uterus.

Near the end of pregnancy, the discharge may contain streaks of thick mucus and/or blood as the cervix thins out and prepares for delivery. This is likely the dislodging of the mucus plug, which could occur gradually or all at once.

Any “colored” discharge, foul odors, itchiness, or soreness could indicate an infection and women should call their HCP.

Swelling

As the uterus grows, it interferes with blood flow from the lower part of the body to the heart. This causes extra blood and fluid to collect in the pelvic region, which puts pressure on nearby blood vessels (venous congestion) and causes them to swell (varicosities).

Varicosities in general can appear as early as 26 weeks of pregnancy. Vulvar varicosities, which are vein swellings on the external genitalia, occur in about 2% to 4% of pregnancies, and vaginal (internal) varicosities occur even less.

Vaginal varicosities are very, very rare, and occur inside the vaginal canal. Only 10 cases have been formally documented in the last 50 years.

Vulvar varicosities are varicose veins at the outer surface of the female genitalia (vulva) and are seen more frequently than internal varicosities.

Vulvar varicosities can cause discomfort, pain, and a feeling of fullness, pressure, or soreness in the vulvar area and appear noticeably swollen. They may also be bumpy and bluish in color.

Long periods of standing, exercise, and sex can worsen these varicosities, which generally regress or feel better when the woman is lying down (albeit temporarily). Fortunately, they disappear completely after delivery, either immediately or within several weeks.

However, vulvar varicosities tend to develop earlier and grow larger with each subsequent pregnancy.

Women should always call their HCP to make sure the swelling is in fact a varicosity, rather than an inguinal hernia or Bartholin's gland cyst.

Women may have concerns that certain severities of vulvar varicosities could increase the risk for hemorrhage/blood clots during vaginal delivery/postpartum, depending on their location – such as a varicosity blocking or partially blocking the vaginal opening. It is noted that this is observed in theory and has not been clinically documented to be the case.

These veins tend to have low blood flow; even if a rupture occurs, they can usually be controlled. Further, the baby's head appears to shrink and compress these veins during delivery, further decreasing risk.

Therefore, it is not necessary to have a cesarean section due solely to the presence of varicosities. However, it is recommended each case should be managed and assessed by HCPs on an individual basis.

If women are concerned, some hospitals can have resources on standby during delivery (such as a vascular surgeon) in the unlikely event a rupture/tear occurs.

Delivery/Postpartum

The vagina undergoes dramatic changes during pregnancy to allow for labor and delivery.

The vaginal tissue (i.e. collagen) and smooth muscle reorganize and change their mechanical properties to allow for a significant amount of stretch. This stretch helps the vagina avoid trauma and injury during the pushing and crowning stages.

Collagen is the primary component contributing to the vagina’s physical stability and remodeling, very similar to the same mechanisms in which the cervix is also able to dilate and stretch.

After delivery, the stretched birth canal does diminish in size, but rarely returns to pre-pregnancy size/dimensions. However, most structural properties of the vagina return to normal around four weeks postpartum, especially after the first delivery.

Rugae, which are ridges inside the vagina, can reappear as early as the third week postpartum, but rugae may also never return for some women, especially those who have had two or more vaginal deliveries.

Additional changes may occur to the vaginal opening after delivery, depending on whether a woman tore or had an episiotomy.

Vaginal dryness can also occur in the postpartum period as hormone levels change (especially in breastfeeding women). Women should contact their HCP if this dryness causes pain, itching, severe discomfort, or hinders healing after delivery.

Action

Any “colored” discharge, foul odors, itchiness, or soreness could indicate an infection and women should call their HCP.

If a pregnant woman chooses to use a bath bomb or other fragrant bath products, she should be well informed of the signs of infection and irritation mentioned above, and if an infection or allergic reaction is suspected, she should see an HCP immediately for treatment.

There is little information on the management of vaginal swelling and vulvovaginal varicosities, and support garments made for vaginal swelling may not be very effective. Women who have varicosities in the vaginal area should be assessed by an HCP who may be able to provide management strategies and rule out other possible conditions.

Women experiencing vaginal swelling should change positions often and avoid standing or sitting for a long period of time, and lie down on their left sides to relieve pressure.

Applying a cold compress to the vagina may help with pain or discomfort, similar to the same technique used for postpartum healing.

Exercise may also be helpful through the improvement of circulation, which can also decrease swelling in the entire pelvic region.

Women should also read more information regarding the safety of sex during pregnancy.