First Trimester Viability

Early pregnancy ultrasounds are valuable to confirm a pregnancy, rule out ectopic pregnancy, and identifying if there is more than one embryo.

However, an early ultrasound also carries the risk of uncertainty – being told a miscarriage may or may not occur. An early ultrasound can lead to a diagnosis of potential miscarriage that turns out to be viable, as well as a viable pregnancy that later miscarries.

Based on current data, after a diagnosis of intrauterine pregnancy of uncertain viability (IPUV), there is no good way to determine if a pregnancy is viable – prior to a follow up ultrasound. Measurements of embryonic structures have wide variability, ultrasound technicians can be off by several millimeters, ovulation could have occurred later than expected, and the fetal heart rate may be at the lower end of what is still considered to be normal.

Organizations have tried to identify and formalize certain cut-off values of visible embryonic structures to predict miscarriage risk and to avoid misdiagnosis of IPUV, but this science is still very imperfect.

Unfortunately for women and couples who receive an IPUV "diagnosis", the wait between ultrasounds is emotionally draining, and women/couples are stuck in "limbo", unsure if they should continue to celebrate their pregnancy or prepare themselves for loss.

Women who experience this scenario should make sure they understand fully what their HCP has described. Women should also ask their HCP as many questions as they need to, take one day at a time, and do their best to find adequate emotional support as they wait for more answers.

Background

In the first trimester, viability is the ability of the embryo to survive and continue to grow successfully, without resulting in miscarriage.

In the second and third trimester, it is defined as “the capability of a fetus to survive outside the uterus".

The term intrauterine pregnancy of uncertain viability (IPUV) has been applied to any situation in the first trimester where viability is uncertain. The rate of IPUV at the first prenatal visit may vary from 10% to 29% of all pregnancies.

The gestational sac, yolk sac, fetal or embryonic pole (early embryo), and heart rate are all measured via ultrasound in early pregnancy. These measurements are compared to gestational age to determine potential viability of the pregnancy.

This system is not perfect; measurements can vary per examiner (where 1 millimeter/1 day makes a difference), and the gestational age could be wrong. Further, the lowest cut-offs for these measurements that indicate potential miscarriage are not known with complete certainty.

An early ultrasound could show:

No gestational sac

Empty gestational sac (sac with no embryo or related structures)

There is an embryo but no heartbeat

There is a heartbeat but it may be too slow

The heart rate is in the expected range but the embryo is measuring smaller than expected for gestational age

All these scenarios could turn out to be viable pregnancies after a follow-up ultrasound (depending on numerous variables) which is usually recommended one or two weeks later.

However, although a follow up ultrasound usually provides much more clarity on viability, it can also confuse things further when growth still is not exactly what was expected.

Waiting for a follow up ultrasound can be emotionally draining for parents trying to celebrate a pregnancy, while also trying to protect and prepare themselves for possible heartbreak. Unfortunately, based on current data, there is no good way to determine miscarriage risk of an IPUV, prior to a follow up ultrasound, unless values fell well outside established normal ranges.

Gestational Age

The first step in determining potential viability is estimating gestational age. Gestational age is usually a best-guess and is never truly known (to the day) with exact certainty unless artificial reproductive technology was used. If gestational age is assumed, but is wrong, it can lead to misdiagnosis of IPUV.

There are numerous factors to consider:

Typically, the “due date” is based on a 280-day gestation from the first day of the last menstrual period (LMP). This is also a far from perfect algorithm, because it falsely implies:

All women have regular cycles

All women ovulate at exactly the midpoint of their cycle

Fertilization always occurs the day of ovulation

All women implanted at the same time

All women correctly recall their menstrual data/history

All women are free from hormone-based birth control methods for at least several months

Note: There have been attempts to improve how due dates are calculated. Read more.

Additionally, first-trimester transvaginal ultrasound itself has an accuracy of 5 to 7 days on either side. Further, a pregnancy in a retroverted (“tilted”) uterus can appear 1 to 2 weeks behind.

Gestational Sac

The first evidence of pregnancy seen on ultrasound is the gestational sac; it is possible to identify the sac with transvaginal ultrasound by 4 and 5 weeks of pregnancy when it is only 2 to 4 millimeters (mm) in size.

It has generally been understood, that between 5 and 7 weeks of pregnancy, both the embryo and gestational sac should grow at approximately 1 mm per day. Recent research indicates, however, that gestational sac diameter may grow at different rates between women.

The point at which the gestational sac becomes a certain size and the yolk sac or embryo should be seen has not been established beyond doubt. If the gestational sac is smaller than expected with no embryo or yolk sac, but no pain or vaginal bleeding is present, it is possible the gestational age is incorrect.

There could also be slight measurement error. At least one study indicated that different ultrasound examiners can vary regarding measurements of the same structures at the same time in the same woman. For example, the mean sac diameter measurement of 20 mm by one examiner could be measured by a second examiner as anywhere between 16.8 and 24.5 mm.

These differences in assessment matter because of the guidelines used to diagnose potential IPUV. If guidelines indicate the yolk sac should always be seen by transvaginal ultrasound when the mean gestational sac diameter is greater than 7 mm, then the smallest change in caliper placement could potentially determine an incorrect IPUV diagnosis (it could also do the reverse).

The HCP will also look for “trophoblastic reaction”, or the thickness of the blood flow from the chorionic villi (umbilical arteries) around the gestational sac, which helps determine the chances of positive viability.

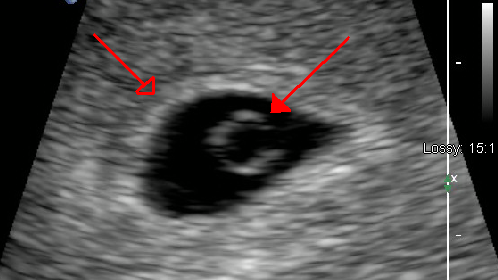

Yolk Sac and Fetal (Embryonic) Pole

The yolk sac is the first structure often seen within a gestational sac measuring 8 to 13 mm (5 to 6 weeks of pregnancy) and it confirms an intrauterine pregnancy.

There is usually one round yolk sac per embryo (including in identical twins).

The biological functions of the human yolk sac have rarely been studied and thus are poorly understood, but it is theorized to be a source of early nutrition.

The yolk sac is measured in early pregnancy as its size can also provide clues for viability. The yolk sac increases in size, becomes less dense, and swells just prior to, or immediately after, an embryo’s heart activity stops. Therefore, a very large yolk sac (larger than 6 mm) is strongly associated with miscarriage, although not completely definitive.

In a viable pregnancy, the yolk sac degrades beginning around 10 weeks of pregnancy and is undetectable via ultrasound by the end of the first trimester.

Embryo and Crown-Rump Length (CRL)

The fetal (or embryonic) pole is seen on ultrasound as a thickening of one side of the yolk sac, which is the first sign of a developing embryo.

The fetal pole is usually identified around 6 weeks of pregnancy with transvaginal ultrasound (when as small as 1 to 2 mm in length) and closer to 7 weeks of pregnancy with abdominal ultrasound.

Crown-rump length (CRL) is the measurement of embryonic length, from the vertex of the skull (crown), along the curvature of the spine to the midpoint between the rump of the developing embryo, and is stated in millimeters or centimeters.

Previously, from 6 weeks to 9 1/2 weeks of pregnancy, CRL was believed to grow at a rate of about 1 mm per day. However, more recent studies have shown CRL grows at variable rates, although 1 mm may be the average.

When CRL is less than 5 mm, up to one-third of embryos will not have a heartbeat yet via ultrasound. When CRL is greater than 7 mm, a fetal heartbeat should be detected. If a heartbeat is not detected at greater than 7 mm, miscarriage is generally expected.

However, accuracy and reliability is best when the CRL is at least 10 mm, and the lowest threshold of a CRL at which a heartbeat should be detected has not been established with absolute certainty. There are also no international standards for relating CRL to gestational age.

An alternative measurement of CRL has been offered as the greatest length, in which the embryo is measured in a straight line without any attempt to straighten the natural curvature of the embryo. Some researchers find this method more useful, but it is not routinely used.

Note: A one-time measurement of human chorionic gonadtropin (HCG) levels also does not help determine viability. HCG levels have a wide range of viability, and the rate of doubling can take 2 to 5 days in some viable pregnancies. It recommended that HCG levels are also reassessed in a week or two for comparison.

Heart Rate

The fetal heart rate in comparison to gestational age is also often used to determine potential viability. By the very start of the 5th week of gestation, the the embryo should have a heartbeat.

Pregnancies in which the embryo has a rapid early heart rate have a good prognosis, with a high likelihood of normal outcome; this is because an early rise coincides with the correct development of the heart. However, the boundary between slow and normal heart rates has not been established.

The presence of a heartbeat after 5 to 6 weeks of pregnancy, or once the embryo reaches 2 mm in length, is associated with a less than 3% to 6% risk of spontaneous pregnancy loss.

In healthy fetuses, the heart rate increases from 110 beats per minute (bpm) at the 5th week of pregnancy to 170 bpm by the 9th week. From then on, there is a gradual reduction in the heart rate to about 150 bpm by the 13th week of pregnancy.

However, slower heart rates can also be normal; it is possible that 100 bpm up to 6 weeks, 2 days of pregnancy, and 120 bpm at 7 weeks of pregnancy, can occur in normal pregnancies, and be the lower rate of normal.

Although "slower" can be normal, research has indicated that fetal heart rates below 90 bpm at 6 weeks, or below 110 bpm at 8 weeks of pregnancy, have been shown to be associated with a very high likelihood of miscarriage (as long as gestational age is correct).

Guidelines

In 2012, guidelines were accepted by the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia regarding measurements of early embryonic structures to determine potential miscarriage. These accepted guidelines indicate:

An empty gestational sac with a mean diameter of greater than 25 mm and/or

An embryo with CRL greater than 7 mm and no detectable heartbeat as a nonviable pregnancy.

The most recommended protocol after the diagnosis of IPUV is to repeat an ultrasound exam within one or two weeks. Comparison of measurements between two scans can reveal much more information regarding potential viability but can also be frustrating if measurements remain borderline.

An empty gestational sac on two scans at least a week apart, the presence of bleeding, and/or the lack of a heartbeat on two scans indicate the highest likelihood of miscarriage.

Action

IPUV is a diagnosis made to assess miscarriage risk, and potentially prepare women for that possibility. However, this causes significant anxiety and frustration. The wait between scans can be excruciating, and women who have been diagnosed with IPUV are scared they may start bleeding at any point.

It is very difficult to remain in a state of limbo. Further, whether or not the presence of pregnancy-related symptoms plays a role in assessing viability is not known. It is possible the presence of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy may be able to add a positive outlook, but again, symptoms in relation to IPUV has not been thoroughly assessed.

Women who face incredible anxiety due to IPUV need to take one day a time, keep themselves distracted (if possible), and remain positive as best they can. It is important to continue taking prenatal vitamins, living a healthy lifestyle, and trying to stay as relaxed as possible despite what may or may not be inevitable.

Finally, if women are having significant difficulty focusing or mentally getting through their anxiety during this time, they should call their HCP with their questions and concerns. HCPs should understand what women go through with this diagnosis, and attempt to provide as much clarity as possible.

Women should also consider sharing their experience below if they ever received an IPUV diagnosis after their first or second ultrasound, to include the outcome (if they know it) and are comfortable sharing (to include instances in which everything continued normally).

Resources

Transvaginal Ultrasonographic Diagnosis of Pregnancy Failure in an Intrauterine Pregnancy of Uncertain Viability (Chart/American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2012; from Early Pregnancy Loss Committee Opinion located here.)

Normal and Abnormal US Findings in Early First-Trimester Pregnancy: Review of the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound 2012 Consensus Panel Recommendations (Radiological Society of North America)