Iodine

In the last few decades, iodine deficiency in the general population is reemerging due to changing diet trends. This also means that pregnant women are entering pregnancy potentially iodine deficient.

Iodine is vital during pregnancy and health care providers (HCP) are beginning to check iodine and thyroid hormone levels during pre-conception appointments, as well as at the first prenatal appointment. Iodine is critical for human health and becomes further necessary as soon as a woman becomes pregnant.

Without enough iodine, a pregnant woman’s thyroid cannot produce enough hormones, which can dramatically affect fetal development – especially the central nervous system. A fetus depends on the mother’s iodine/thyroid hormone status the entire pregnancy.

Women (before and during pregnancy) who are concerned about their iodine levels or thyroid hormone status should talk to their HCPs; pregnant women should never take any supplements without talking to their HCP first.

Women should also consider switching their use of pink (Himalayan) salt, Kosher salt, and other sea salts for iodized table salt during pregnancy. For many women, this may be the only change necessary to ensure adequate iodine intake. Read below to learn why.

Background

NOTE: When iodine is combined with a salt, such as potassium, it is then referred to as iodide (such as potassium iodide or iodized table salt). For consistency, this page will use iodine throughout to avoid confusion.

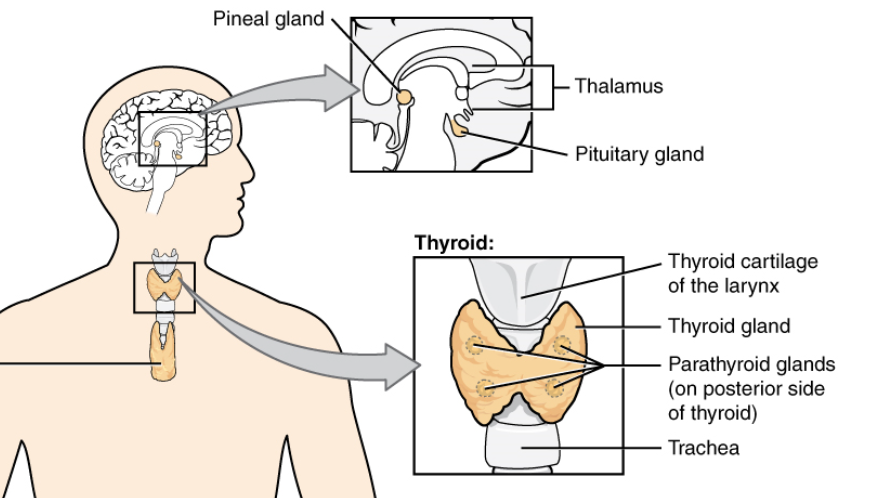

Iodine is an element needed to produce thyroid hormones, which are made by the thyroid gland, a butterfly-shaped endocrine gland located in the lower front of the neck.

Thyroid hormones control the metabolic rate of the body: they help the body use energy and stay warm. They also impact reproductive function, nerves, skin, hair, and keep the brain, heart, muscles, and other organs working properly.

Iodine is quickly and almost completely absorbed in the stomach; when it enters the circulation, the thyroid gland concentrates it in appropriate amounts for hormone production.

Pregnancy

If there is not enough iodine in the body, the thyroid gland cannot make adequate amounts of T3 and T4, which are necessary for fetal development.

Thyroid hormones are crucial for proper skeletal and central nervous system development in fetuses, as well as the development of the surfactant system. They are also necessary for proper fetal heart development, especially in the second half of pregnancy.

Production of T4 increases by approximately 50% to 100% during pregnancy, which in turn, requires an increase in iodine intake.

Depending on the region of the world in which a pregnant woman resides (and how much iodine is available through food), the thyroid gland can be increased in size by 10% to 40%.

The embryo/fetus relies solely on the mother’s thyroid hormones the entire first half of pregnancy; maternal thyroid hormones are found in the embryo as early as 6 weeks of pregnancy.

Receptors for thyroid hormones are present in the fetal brain from 8 to 9 weeks of pregnancy, reaching adult levels by 18 to 20 weeks of pregnancy.

However, the reserves of the fetal gland are low and the gland itself does not fully mature until birth, therefore the fetus still depends mostly on the mother’s thyroid hormones until birth.

Iodine is so important during pregnancy, the Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in Australia and New Zealand indicated that in women who cannot take prenatal vitamins due to severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy, they should only be concerned with two supplements: folic acid and iodine.

Clinical trials results published in July 2021 found that the use of an iodine-containing supplement that was initiated prepregnancy and continued through pregnancy was associated with lower TSH, and higher fT3 and fT4 concentrations, which may suggest improved thyroid function (see Supplementation Guidelines for more information; women should never take iodine supplementation without first speaking with their HCP).

Deficiency

A lack of iodine in the diet may result in the mother and fetus both becoming iodine deficient:

Low amounts of T4 results in damage to the fetus’s developing brain; iodine deficiency is the most common cause of preventable brain damage in the world.

This damage can occur from the very beginning of pregnancy. Nervous tissue begins to develop as early as the second month of pregnancy, and brain damage at this time from a lack of iodine may be irreversible.

Severe iodine deficiency in the mother has also been associated with miscarriage, stillbirth, preterm delivery, epilepsy, congenital abnormalities, and problems with growth, hearing, and speech.

Cretinism is the most severe form of fetal brain damage caused by a lack of iodine in the diet of the mother. This severe level of deficiency causes detrimental effects to the central nervous system.

The potential negative effects of mild-to-moderate iodine deficiency during pregnancy are not as obvious and require further research.

Unfortunately, it is hard to predict which pregnant women may be at risk for, or are currently experiencing, iodine deficiency. Further, “mild”, “moderate”, and “severe” levels of deficiency are hard to define, and cut-off values have not been established.

However, it is possible that even mild iodine deficiency during pregnancy could have an impact on brain development, even if thyroid hormone levels are normal.

Mild-to-moderate iodine deficiency during pregnancy has been associated with reduced IQ scores in children, as well as an increased risk for attention deficit hyperactivity and autism spectrum disorders.

However, in Australia and New Zealand, which have seen the re-emergence of mild iodine deficiency in the last two decades, there appears to be no obvious signs of impaired neurodevelopment, but more research is necessary.

Iodine deficiency can also occur postpartum, especially if breastfeeding. A recent study published in April 2021 found that their cohort of postpartum breastfeeding women was iodine deficient; further, iodine status of their breastfed infants was suboptimal. The authors recommended that lactating women who do not consume iodine rich foods and those who become pregnant again should take iodine-containing supplements (women should talk to their health care provider first).

Reemergence of Iodine Deficiency

There is a reemergence of iodine deficiency around the world:

The overall iodine consumption in the United States (U.S.), Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom (U.K.) has decreased in the last 20 to 40 years, despite widespread availability of iodized salt.

Additionally, in the U.S., there is a higher prevalence of mild iodine deficiency in the pregnant population compared to the general population. Similar findings have been observed in another countries.

Further, it has been reported that in various locations around the U.K., pregnant women are classified as mildly-to-moderately iodine deficient, and deficiency in Spain is so persistent (2020) that prescription potassium iodide is recommended during pregnancy.

The re-emergence in iodine deficiency appears to be due to:

The increased amount of commercially prepared foods – these foods do not use iodized salt, and it is estimated adults consume 80% of their salt requirements through processed foods.

The decreased consumption of dairy products in adults in the U.S. since the 1990s, which previously contributed substantially to dietary iodine intake.

The recent increased trend/use of Kosher, Himalayan, and other sea salts (which contain no iodine).

Increased consumption of soy for various health related diets/concerns; soy intake inhibits iodine absorption and interferes with thyroid hormone production (can be prevented with adequate iodine intake).

Increased reluctance to consume ‘food additives’, which usually contain iodine.

A decreased salt consumption overall due to health messages suggesting a reduction in salt intake to improve blood pressure.

Vegan diets can also be surprisingly low in iodine.

Iodization Programs

More than 120 countries, including the U.S., Canada, Australia, and New Zealand have optional or mandatory salt iodization programs (the U.K. does not, but has made modifications to its dairy industry).

Mild-to-moderate iodine deficiency is common in Europe. Of the total population of approximately 590 million in this region, 350 to 400 million individuals currently have no access to or are not using iodized salt.

Supplementation Guidelines

Ideally, women should have adequate iodine stores (in the thyroid) of 10 to 20 milligrams (mg) pre-conception.

Pregnant women can have their thyroid hormones measured, but there is debate as to whether all pregnant women should be screened for abnormal thyroid hormone concentrations or just those considered at risk.

The Recommended Daily Amount of iodine increases from 150 micrograms (mcg)/day in non-pregnant women, to 220 mcg/day during pregnancy.

The World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund, and the International Council for the Control of Iodine Deficiency Disorders recommend a slightly higher iodine intake for pregnant women at 250 mcg/day.

In Europe, it has been proposed that pregnant women should be given iodine tablets during pregnancy to achieve the recommended 250 mcg/day. The Polish Society of Gynaecologists and Obstetricians also recommends every pregnant woman be given iodine supplementation.

The American Thyroid Association has recommended that all pregnant and breastfeeding women take a daily prenatal multivitamin containing at least 150 mcg/day of iodine.

However, a 2009 survey of 223 prenatal vitamins in the U.S. revealed that only approximately 50% contained any iodine.

NOTE: Many multivitamin/mineral supplements contain iodine in the forms of potassium iodide or sodium iodide. A study revealed that when 150 mcg “potassium iodide” was listed as an ingredient, 23% of the mass was attributable to potassium, providing an average 119 mcg daily dose of iodide.

There is currently no evidence that higher than 220 to 250 mcg/day is beneficial.

Safe upper limits for iodine intake in pregnancy have not been universally established, but it is believed the placenta acts as a barrier to prevent excessively high levels of free T4 and T3 from reaching the fetus until they are needed.

Despite the above, it is still important that pregnant women do not take too much iodine, as higher doses during pregnancy could induce thyroid dysfunction and change the way it works.

For example, seaweed is one of the highest food sources of iodine. Numerous seaweed species significantly contribute to traditional Asian meals, and therefore, the average Japanese dietary intakes of iodine are estimated to range between 1,000 to 3,000 mcg/day. Iodine-induced goiter and hypothyroidism are not uncommon in Japan and is generally reversed by limiting consumption of seaweed.

Fortunately, acute iodine poisoning is rare and usually occurs only with doses of many grams (there are 1,000,000 mcg in 1 gram). Symptoms of iodine poisoning include burning of the mouth, throat, and stomach, and fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, a weak pulse, cyanosis, and coma.

Iodine supplements do have the potential to interact with several types of medications:

ACE inhibitors are used primarily to treat high blood pressure. Taking potassium iodide with ACE inhibitors can increase the risk of hyperkalemia (elevated blood levels of potassium). Hyperkalemia can cause weakness as well as a slow heart beat and weak pulse.

Pregnant women should never take supplements without talking with their HCP first.

Food Sources

Dairy products, seafood, meat, some breads, eggs, seaweed, grain products, fruits, vegetables, and poultry are good sources of iodine.

Seafood is rich in iodine because fish and other marine animals can absorb the iodine from seawater.

Fruits and vegetables contain iodine, but the amount varies depending on the iodine content of the soil, fertilizer use, and irrigation practices. This also affects the iodine content of meats and poultry because of the food they eat.

The amount of iodine in foods is not listed on food packaging in the U.S.

Action

Women should talk to their HCP if they are concerned about their iodine intake or their thyroid hormone levels; they should not take iodine supplementation without first speaking with their HCP.

Instead of increasing salt intake, women who use Himalayan, pink, or sea salt should just simply switch to iodized salt during their pregnancies.

Resources

Iodine Fact Sheet (U.S. National Institutes of Health)

Iodine Deficiency (American Thyroid Association)